ATÚ: Automatic Telephone Exchanges: Society, Technology, Architecture

Automatic telephone exchanges are today one of the most endangered examples of post-war architecture. The analogue communications technologies they were designed for have been replaced with digital platforms, and communication operations can nowadays be handled by equipment in a small server rack. The current owners of these empty, dilapidated buildings are not, however, looking for new uses for these sites. The buildings’ most common fate is that they are sold and then demolished to make way for new construction on the lucrative land they occupy. So what should be done with these buildings that just a few decades ago were among the state’s most high-priority investments? Do they even deserve a place in the history of Czechoslovak architecture?

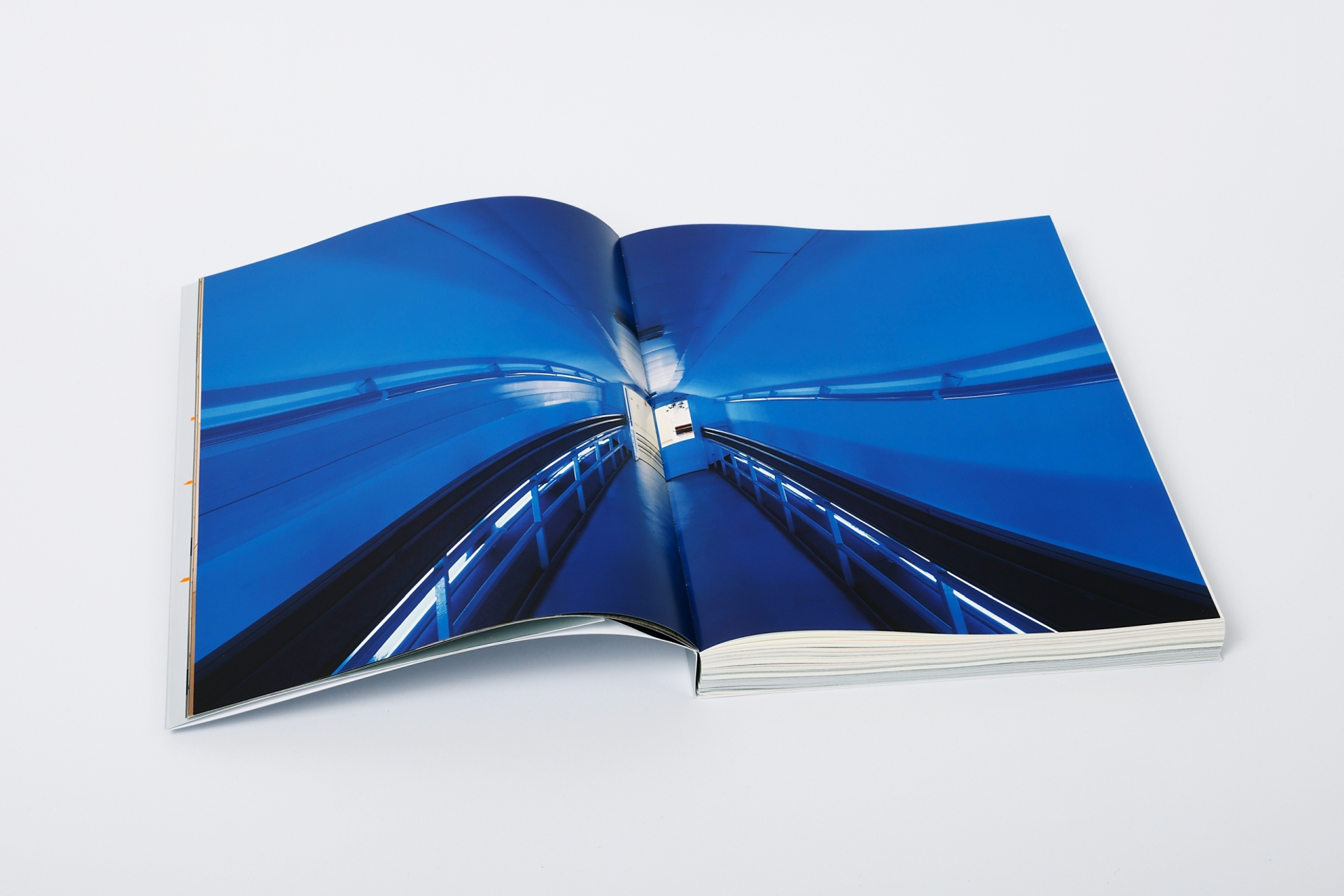

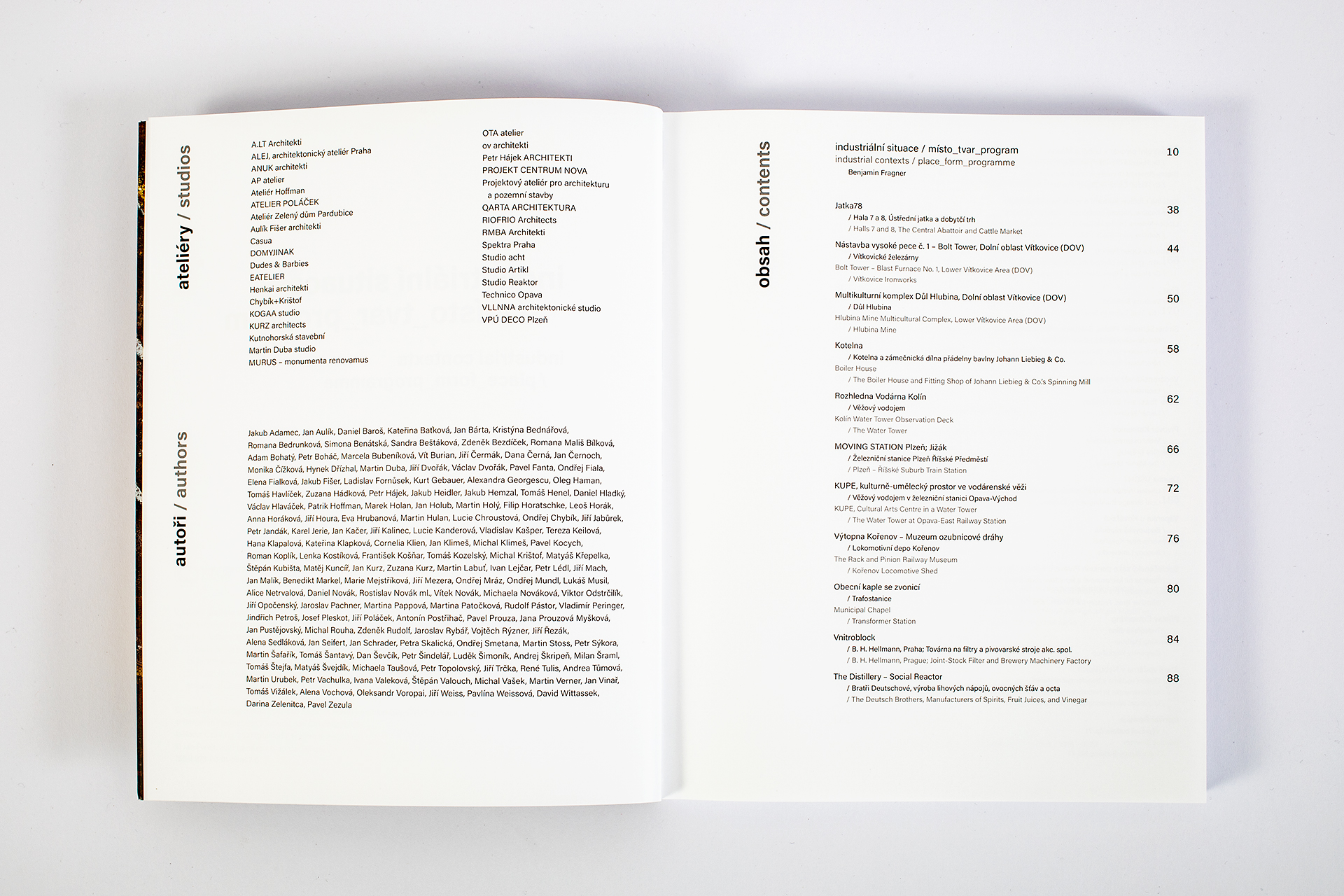

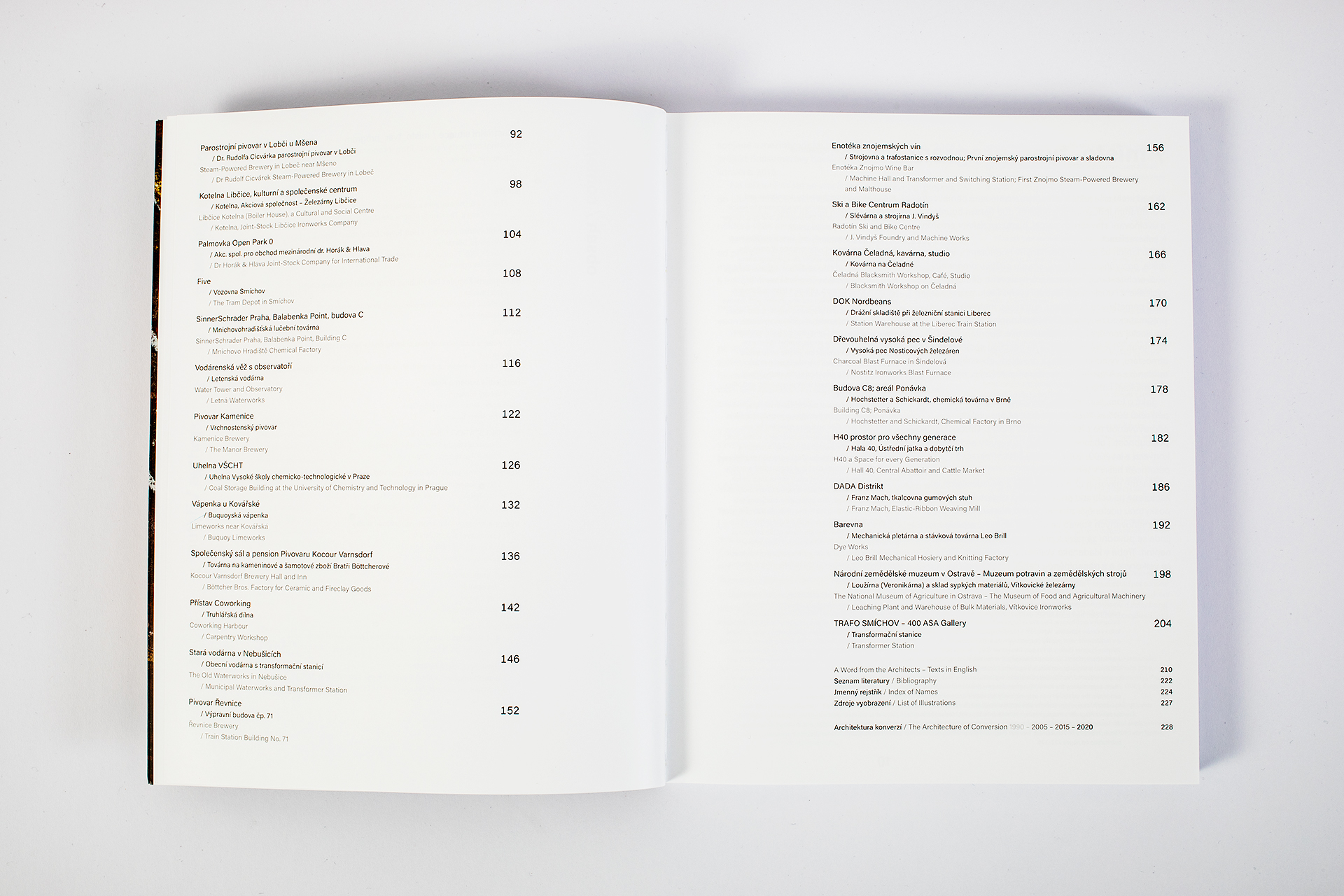

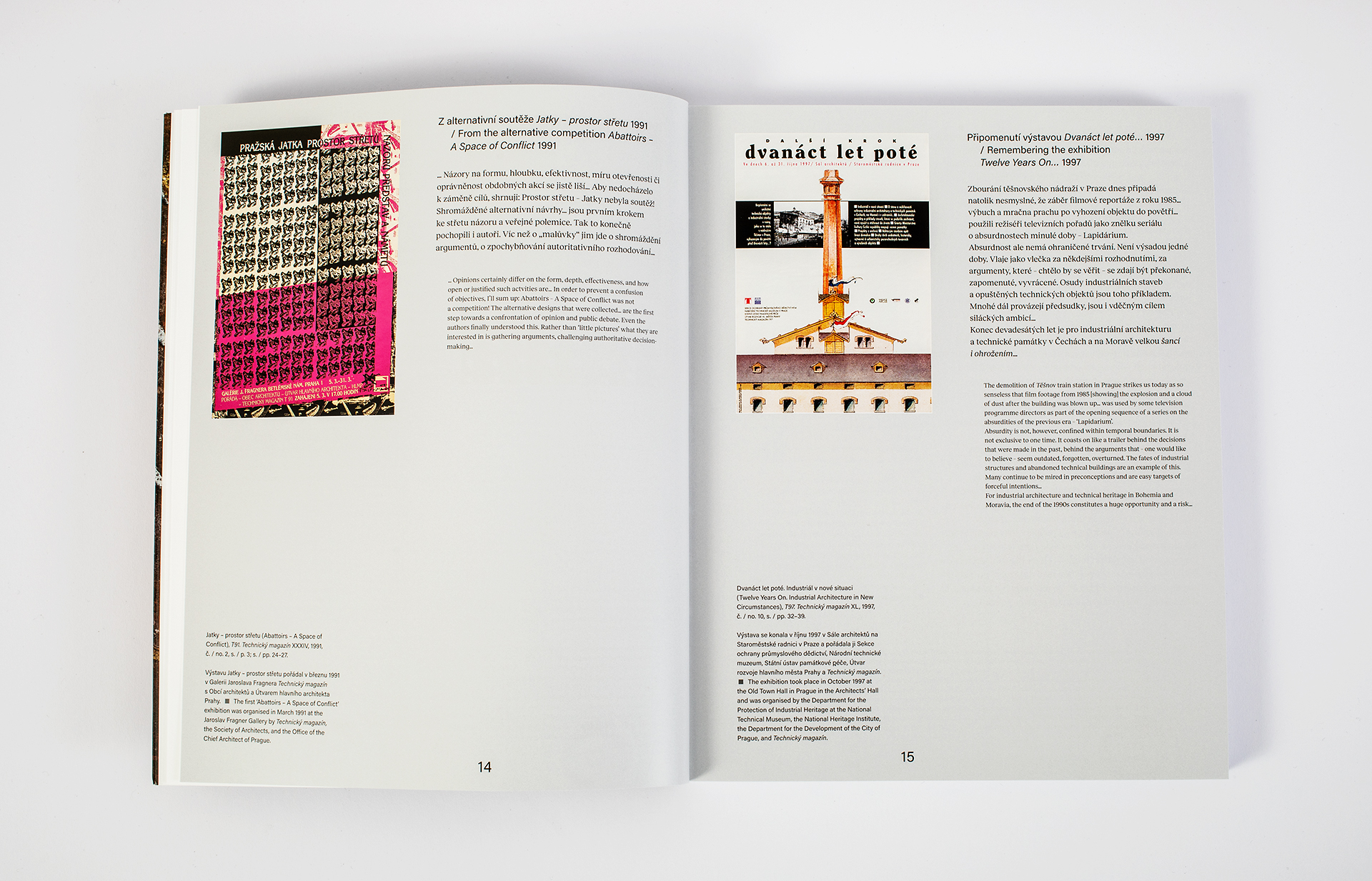

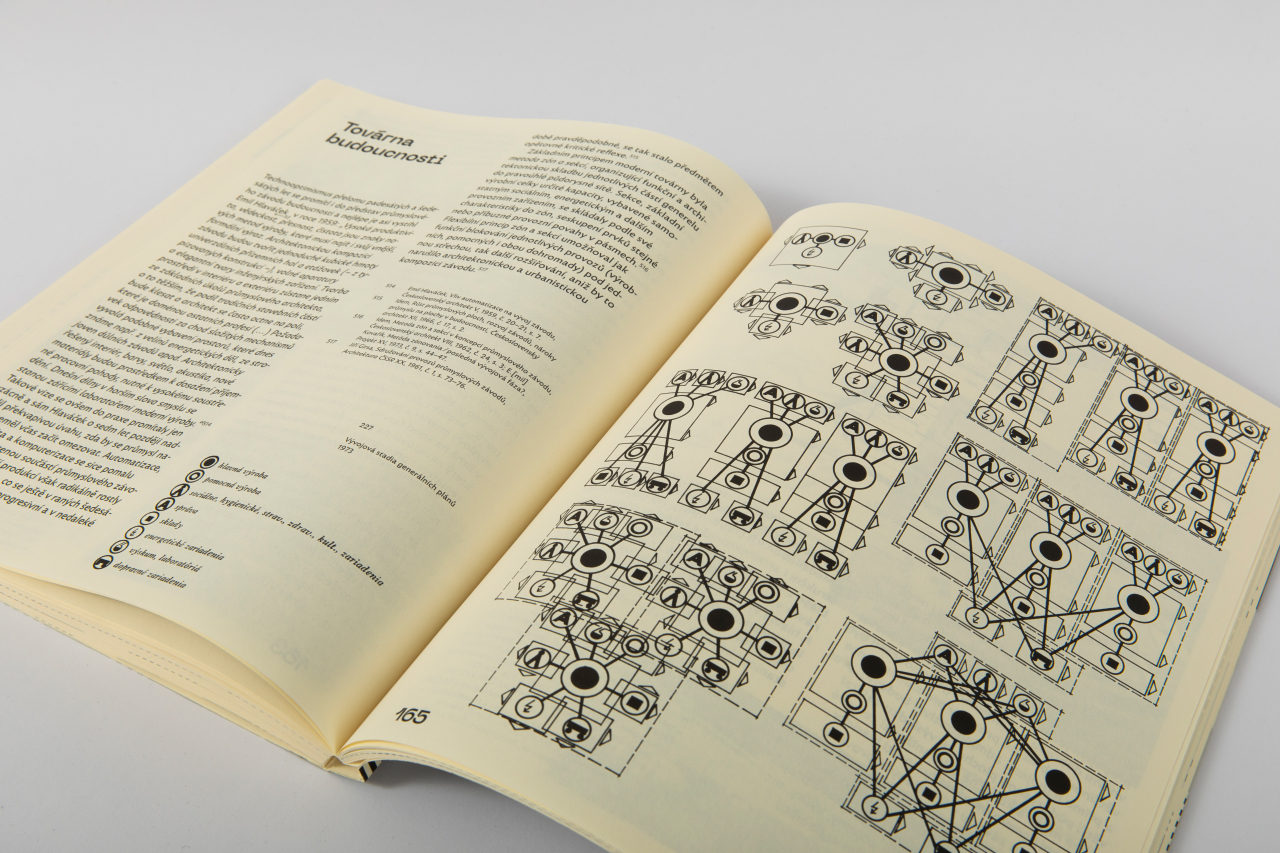

As Benjamin Fragner suggests in his foreword to this publication, expanding the framework of industrial heritage could help us to find answers to these questions. Telephone exchanges share something in common with factories: they are houses for machines and they form the final link in the chain that connects strategies, innovations, and societal need. Capturing these relationships is crucial to understanding this specific architecture. For this reason the book is divided into thematic chapters, each comprising a synthetic study and an appendix covering related subtopics.

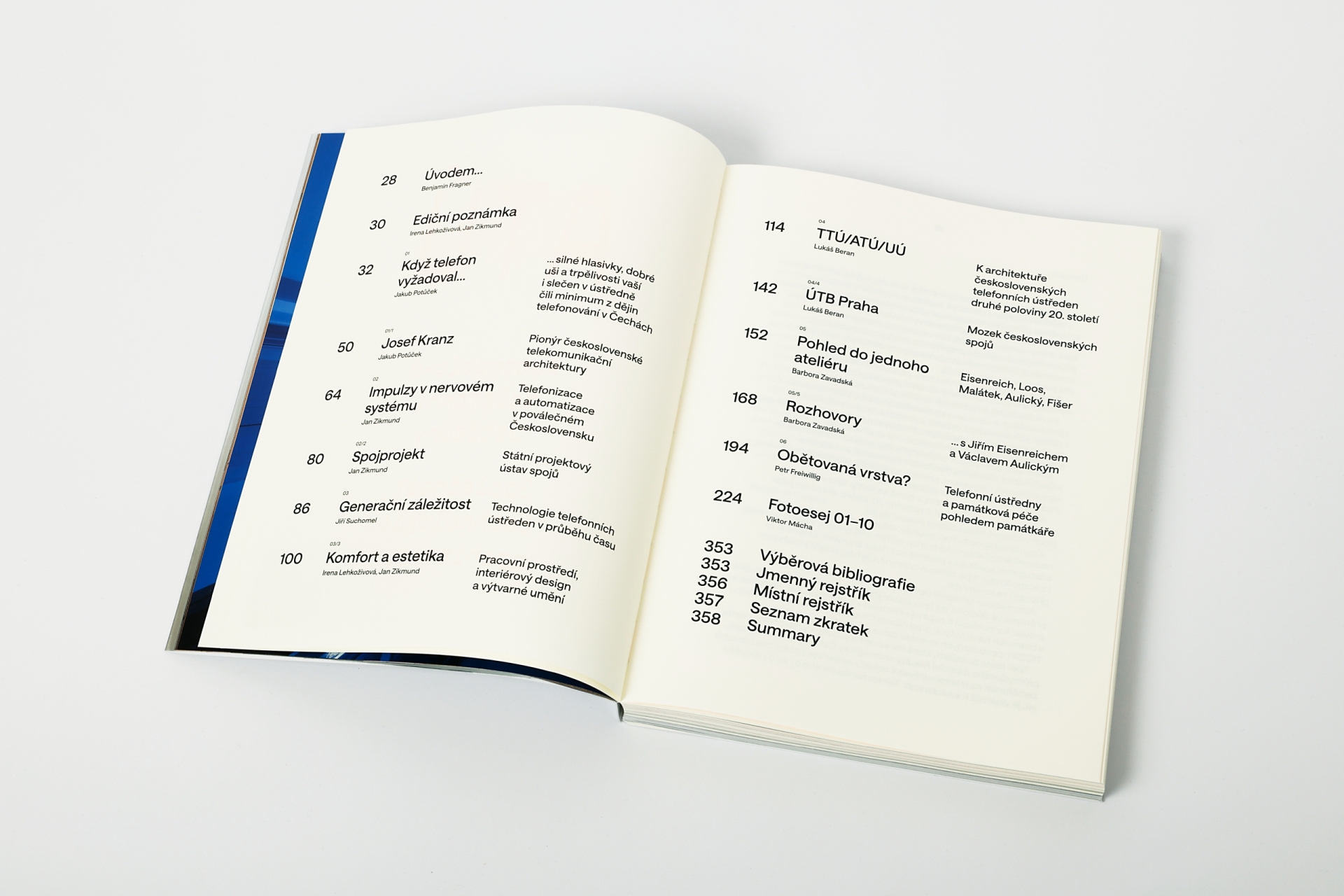

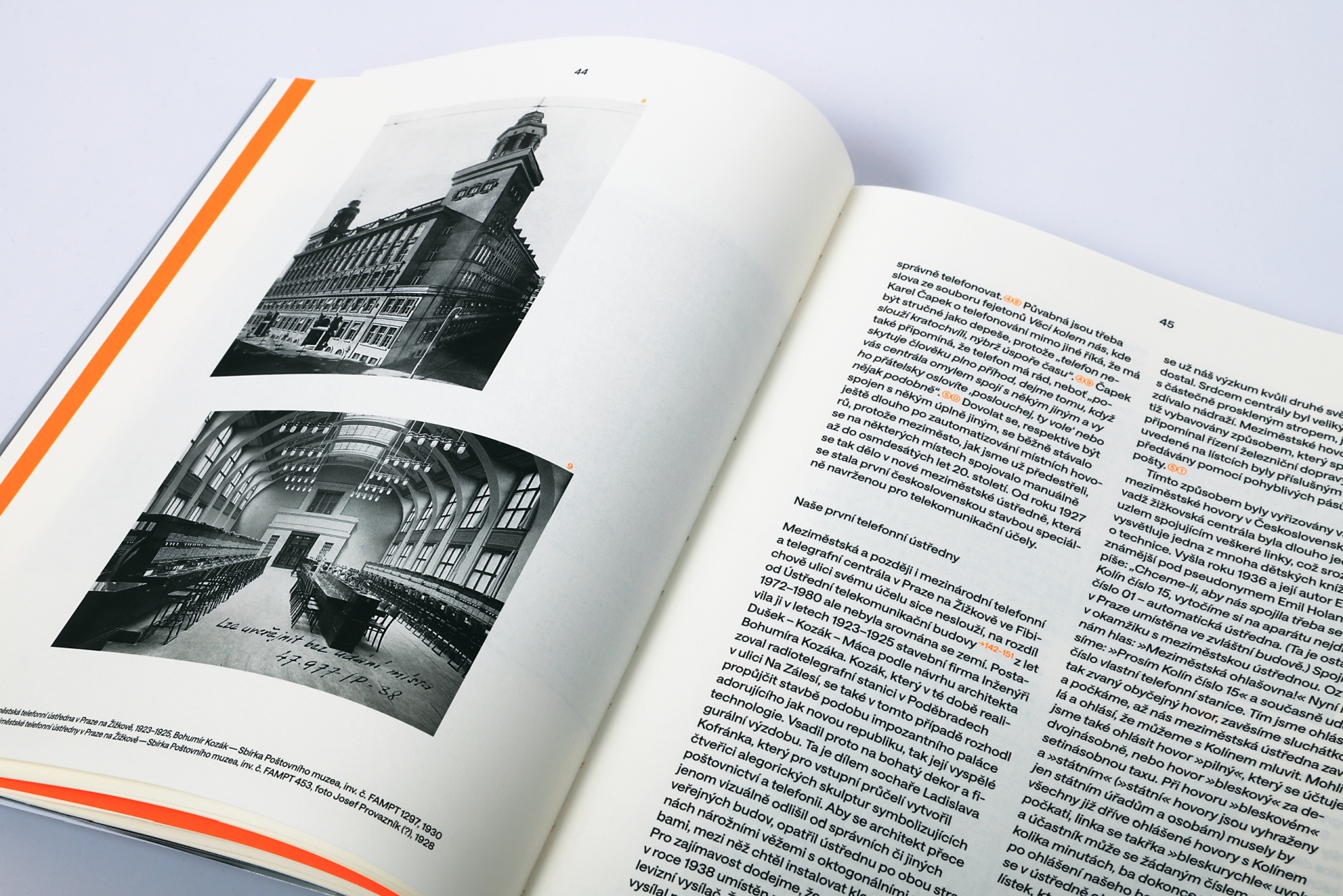

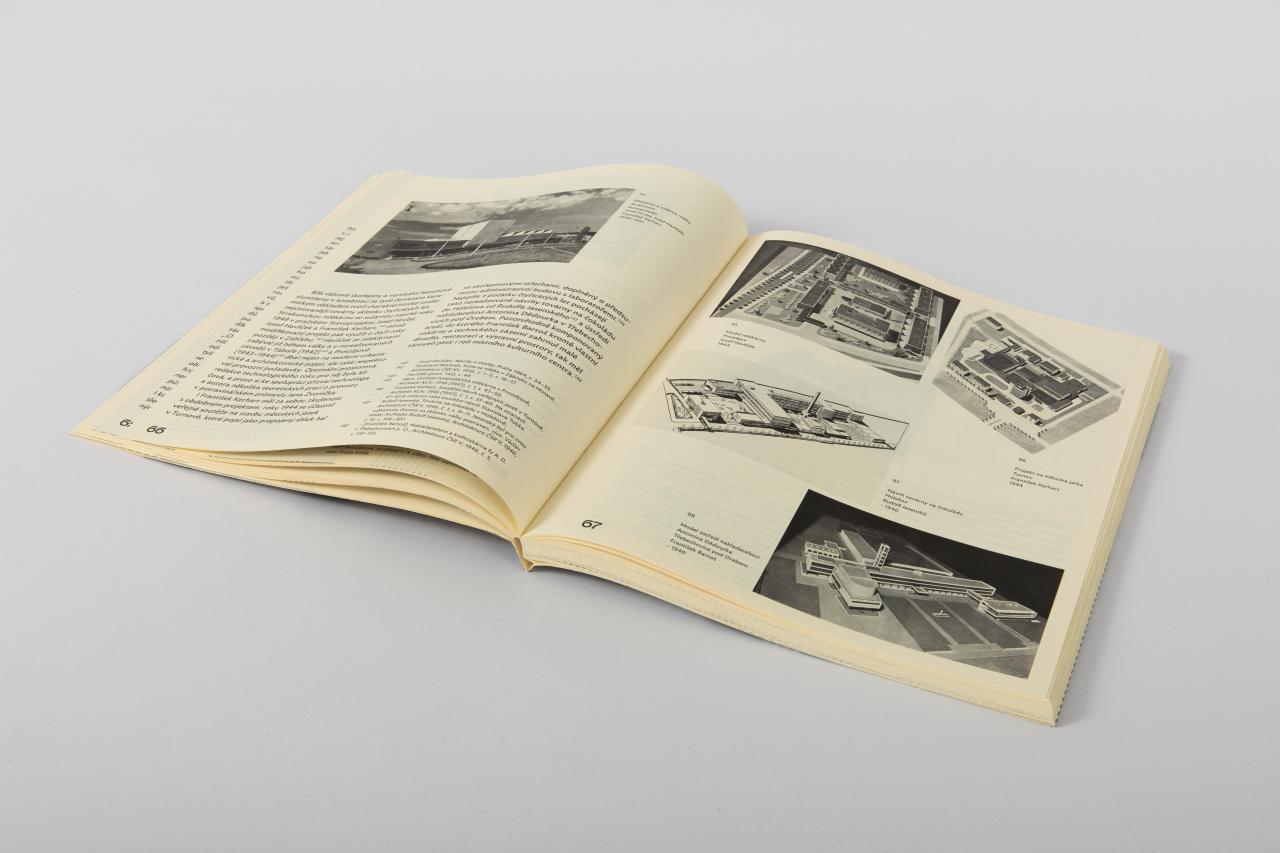

Although the publication is focused on architecture dating from the second half of the 20th century, it is impossible to ignore the important moments in the birth of telephone technology in the Czech lands that fundamentally transformed communication and the perception of time and space. Jakub Potůček, in his chapter ‘Když telefon vyžadoval…’ (When the Telephone Required…), describes the emergence of a new building typology and the rise of the first design specialist in this field. This was Josef Kranz, a now largely forgotten architect from Brno, who is portrayed in this chapter as a designer who brilliantly combined the functional parameters of a technical building with aesthetic considerations in its design.

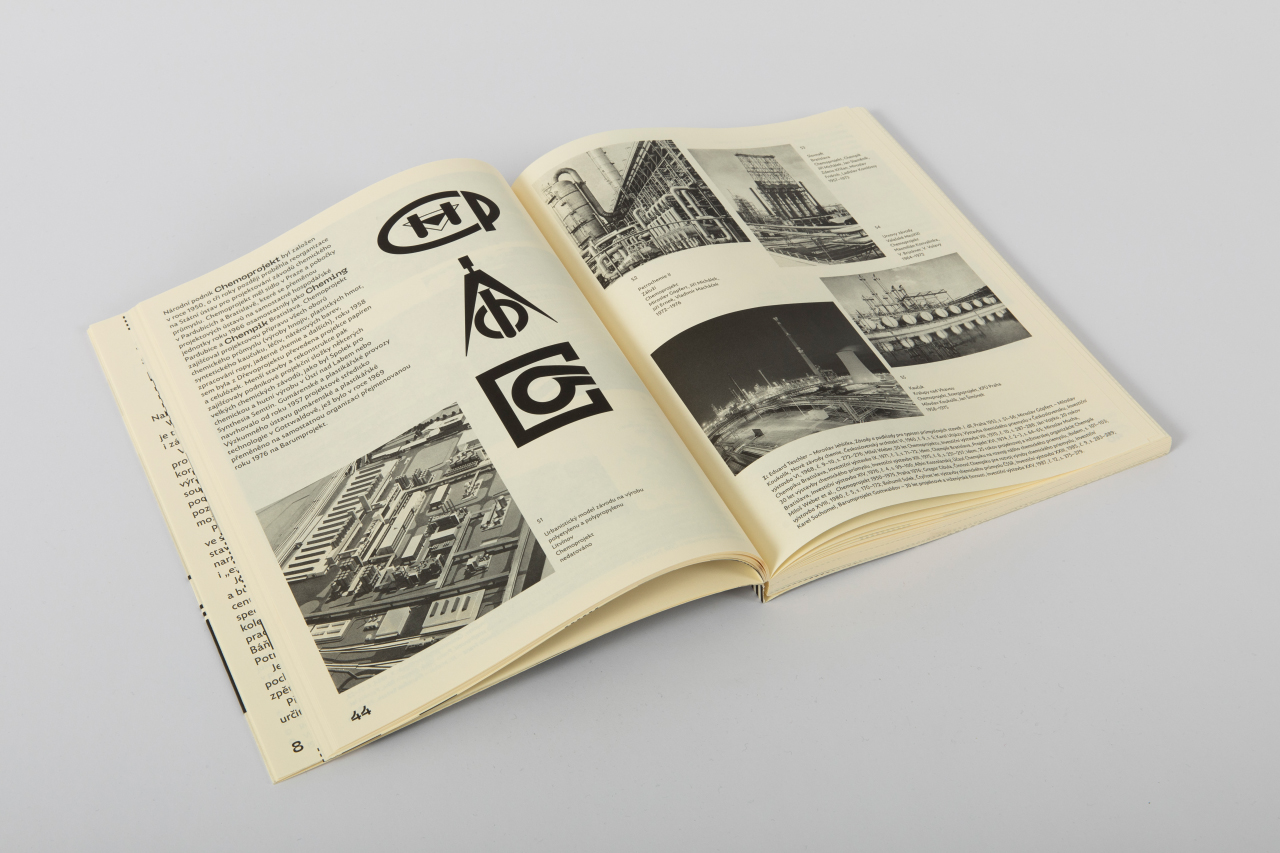

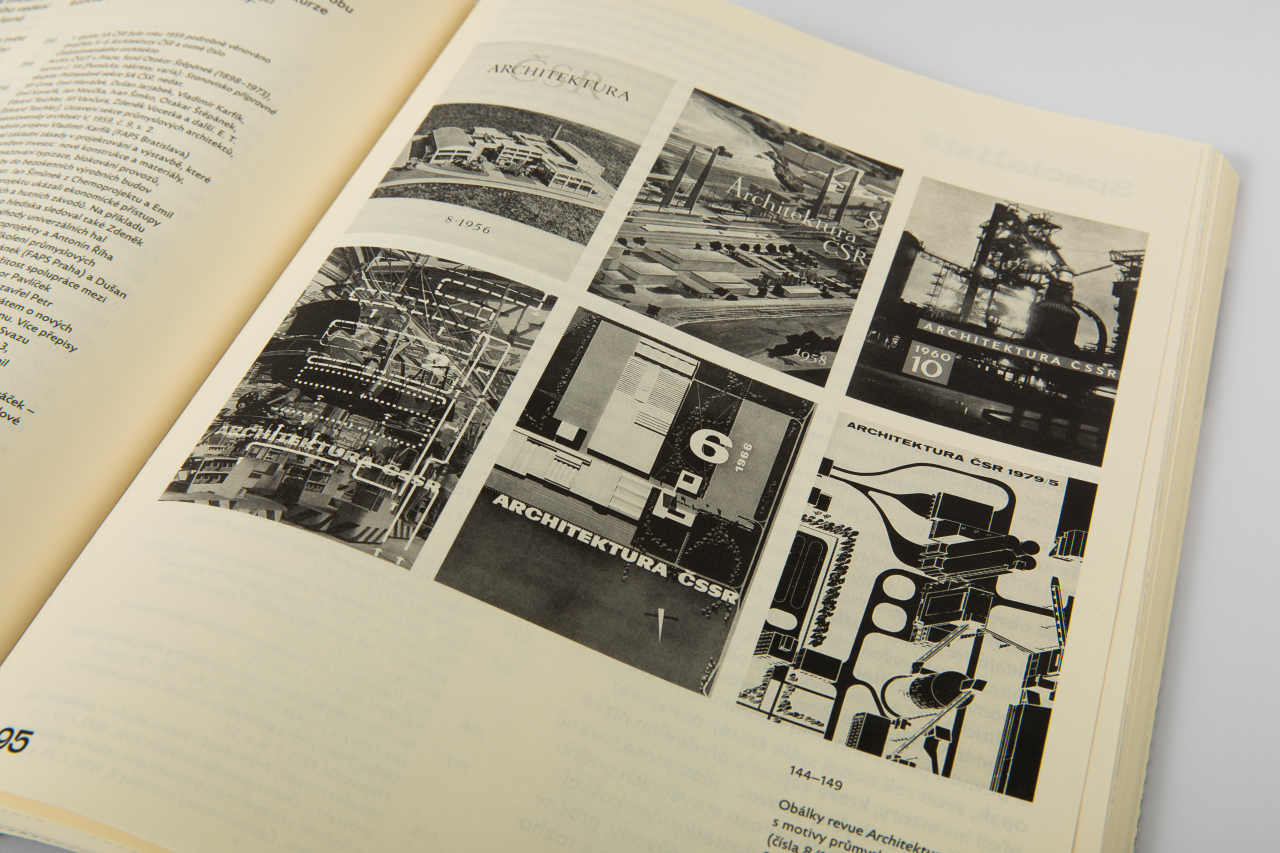

Alongside the development of industry, the advancement of telecommunications was a priority task in Czechoslovakia in the post-war period as it went through a political and economic transformation. Despite organisational interventions in the expert culture of the state apparatus, however, the state only partially succeeded in fulfilling its plans and satisfying demand. The processes that reshaped the structure of professional institutions, production enterprises, and design institutions coincided with a transformation in the way the role of telecommunications was seen in society. An overview of these changes is provided in the chapters ‘Impulzy v nervovém systému’ (Impulses in the Nervous System) and ‘Spojprojekt’ by Jan Zikmund.

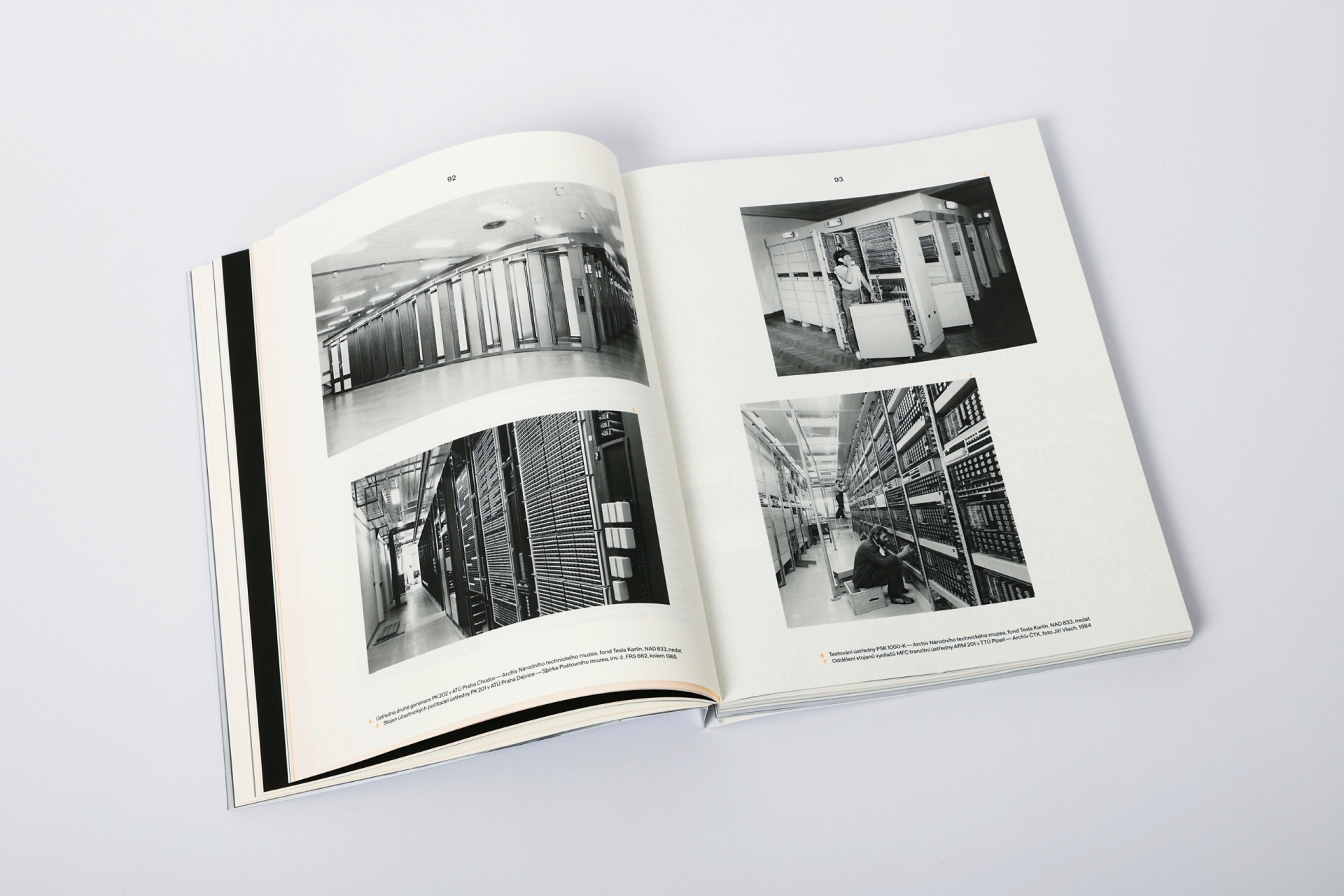

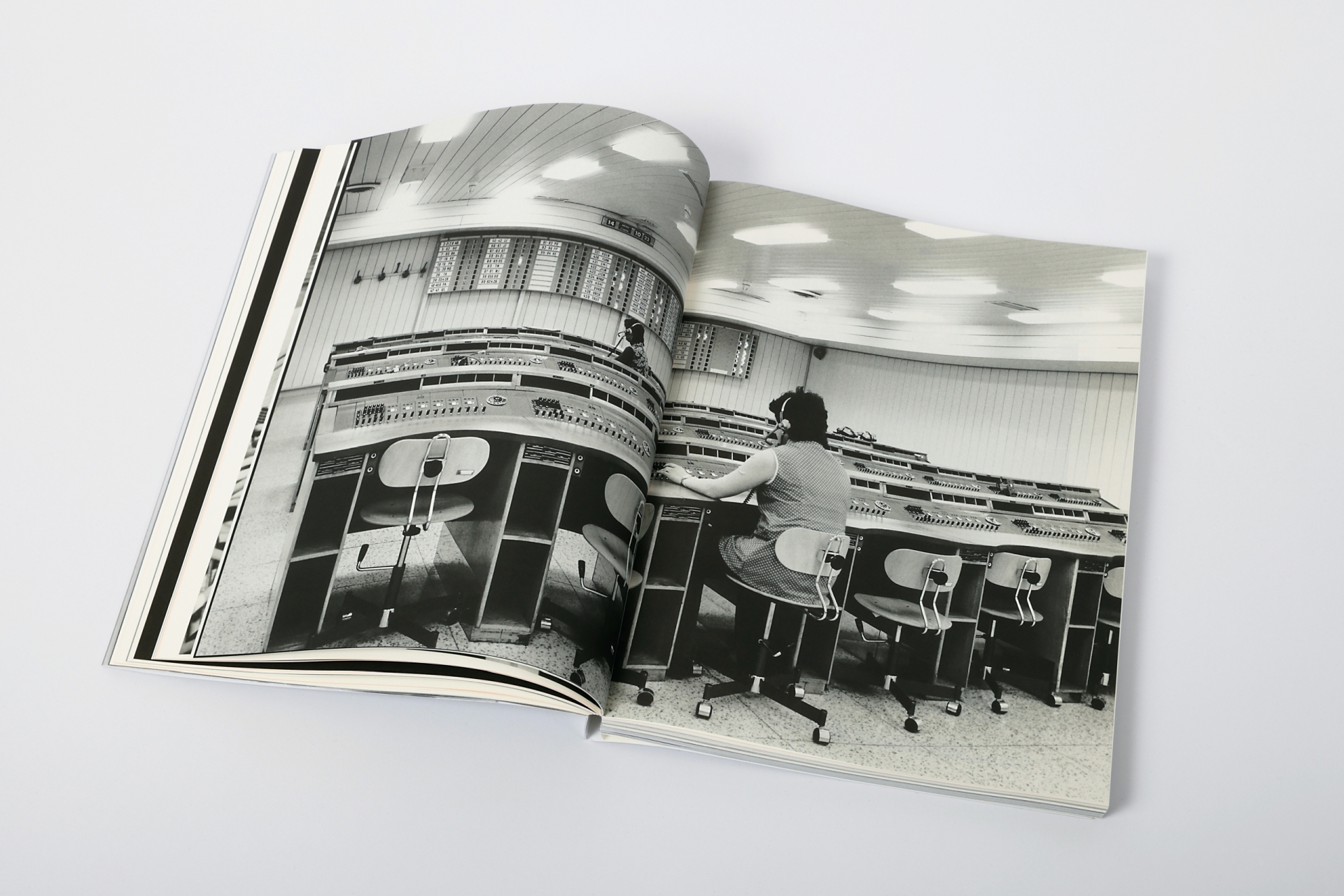

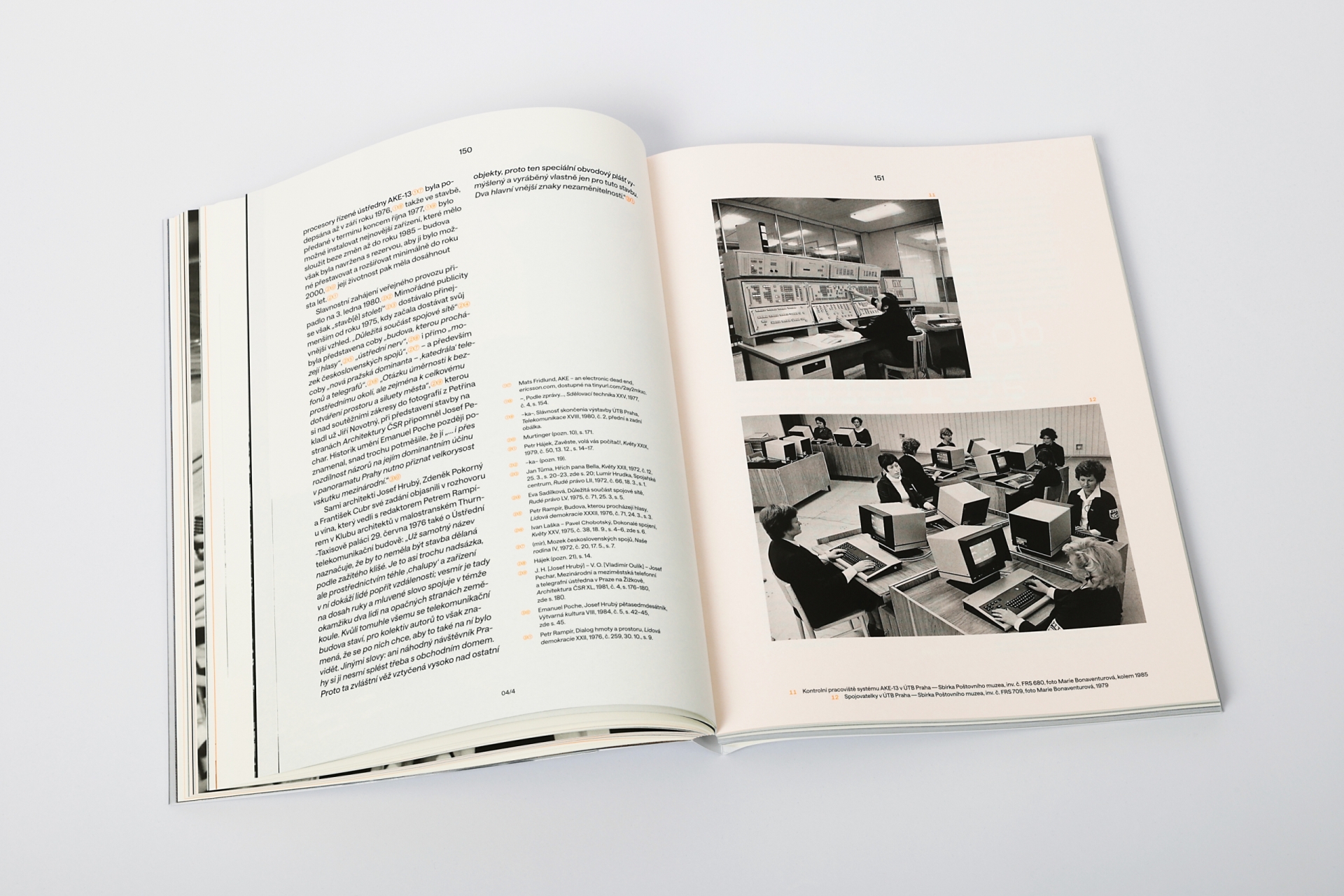

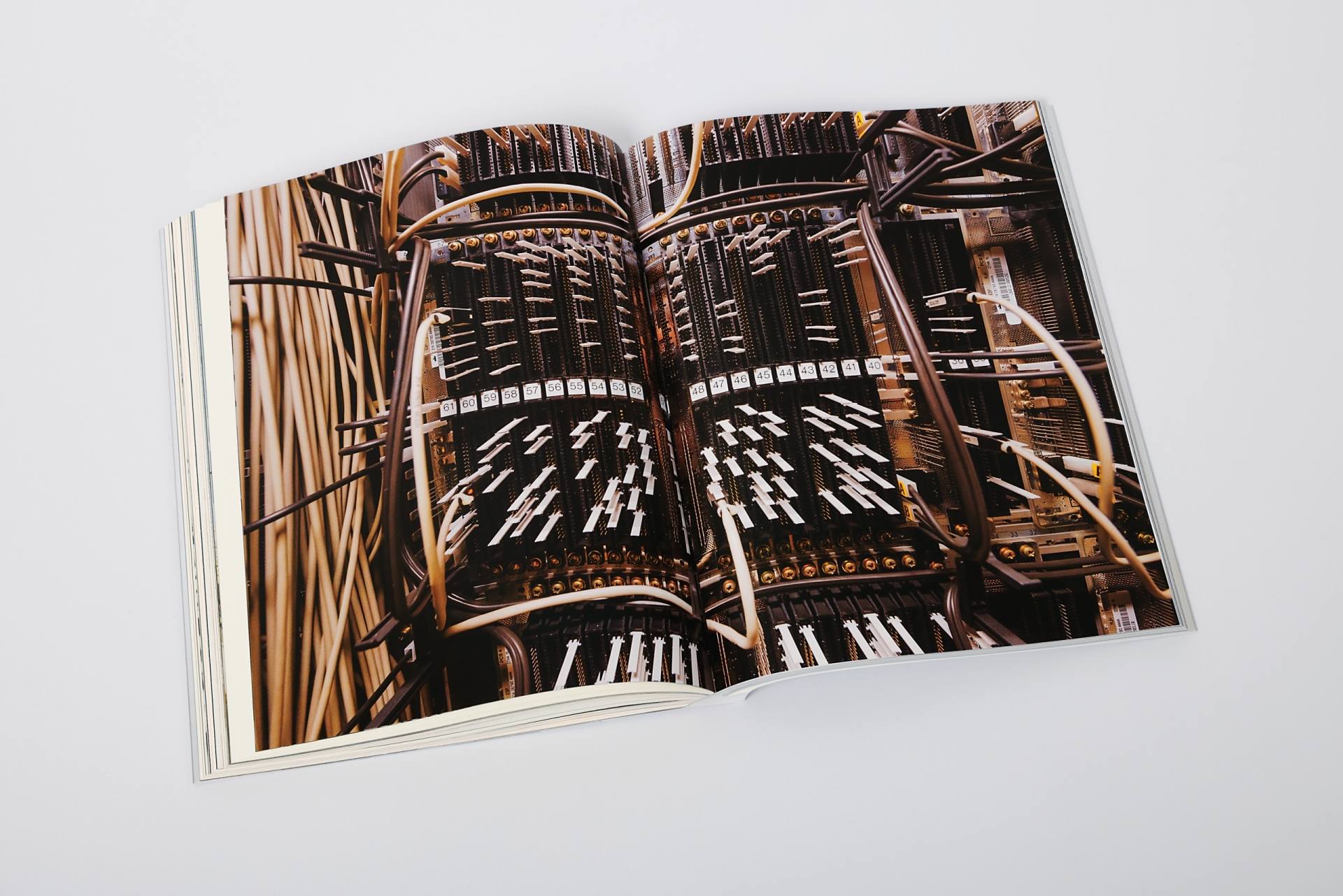

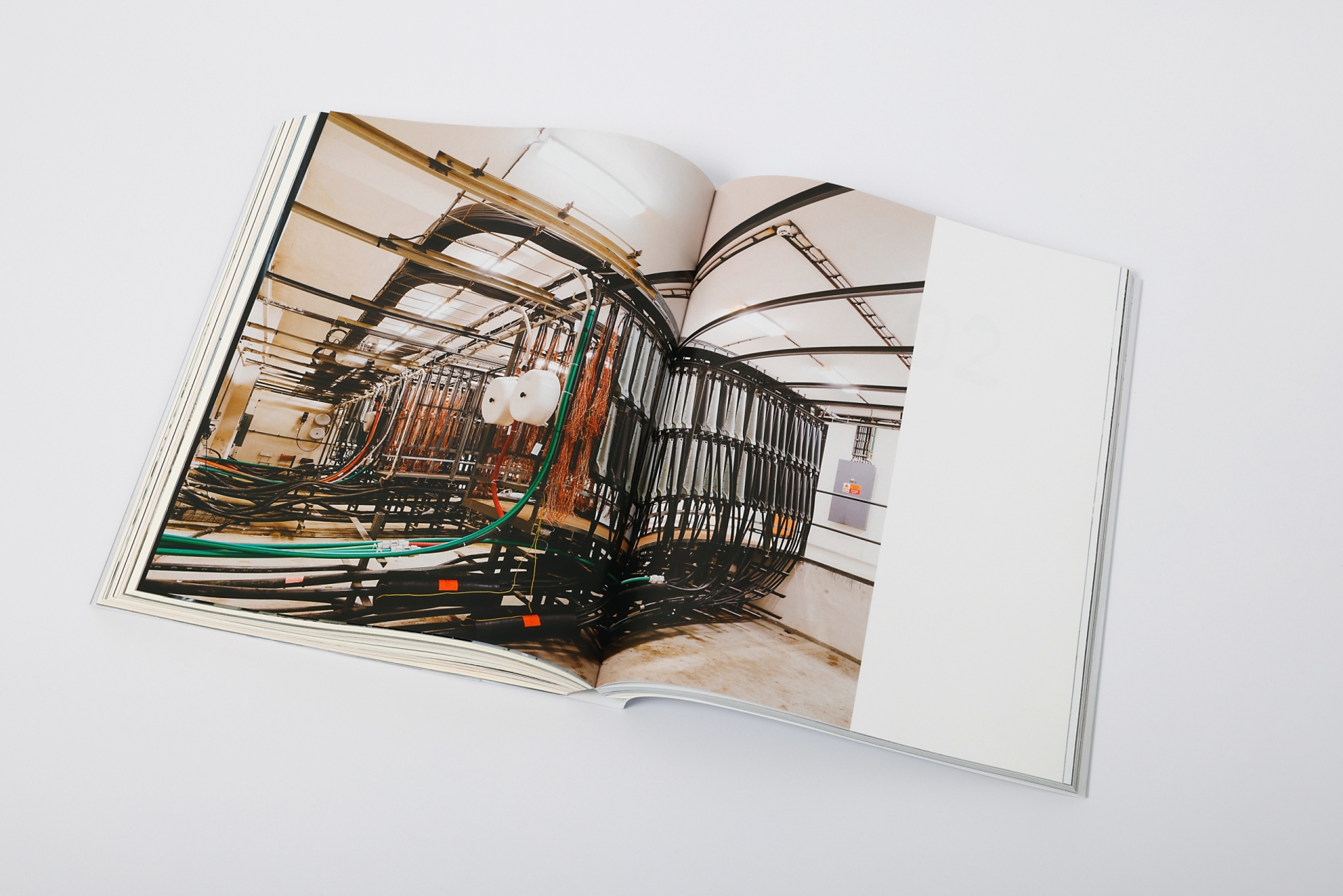

Without advanced communications technology, however, the system as a whole would have been unable to function. As Jiří Suchomel, who initiated systematic mapping and photographic documentation of telephone exchange buildings nearly ten years ago, shows in his chapter ‘Generační záležitost’ (A Generational Affair), the development and production of increasingly powerful and sophisticated machinery did not proceed as planned in the conditions of the Czechoslovak economy, and equipment often had to be imported from abroad. The buildings nevertheless were not exclusively reserved for automatic technologies, as the voices and hands of the women operators, who often worked in substandard conditions, were still needed to connect calls and provide other services. The efforts of telecommunications organisations and architects to create a sophisticated space were reflected also in the design of the interiors and the surrounding area. These aspects are presented in the chapter by Irena Lehkoživová and Jan Zikmund titled ‘Komfort a estetika’ (Convenience and Aesthetics).

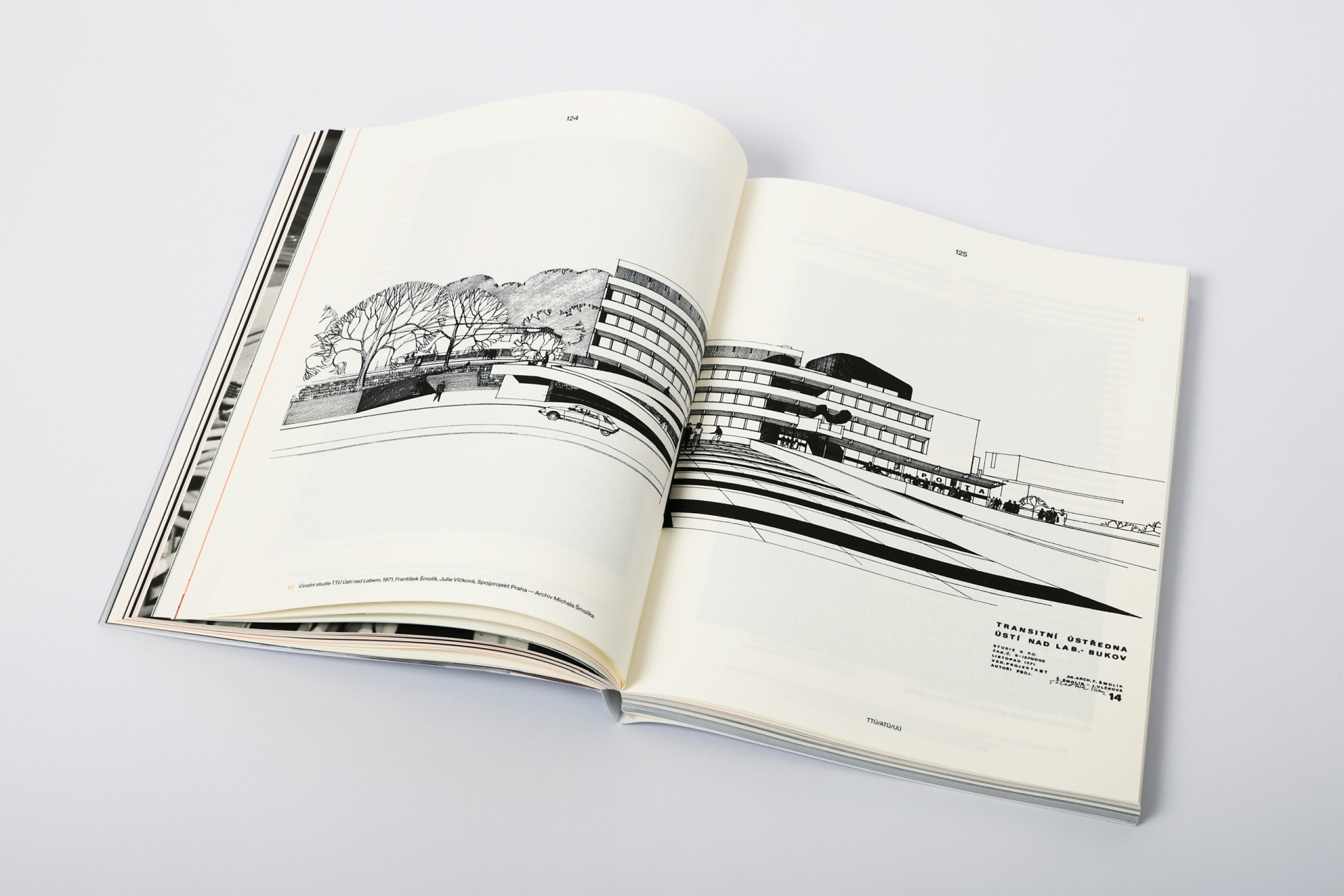

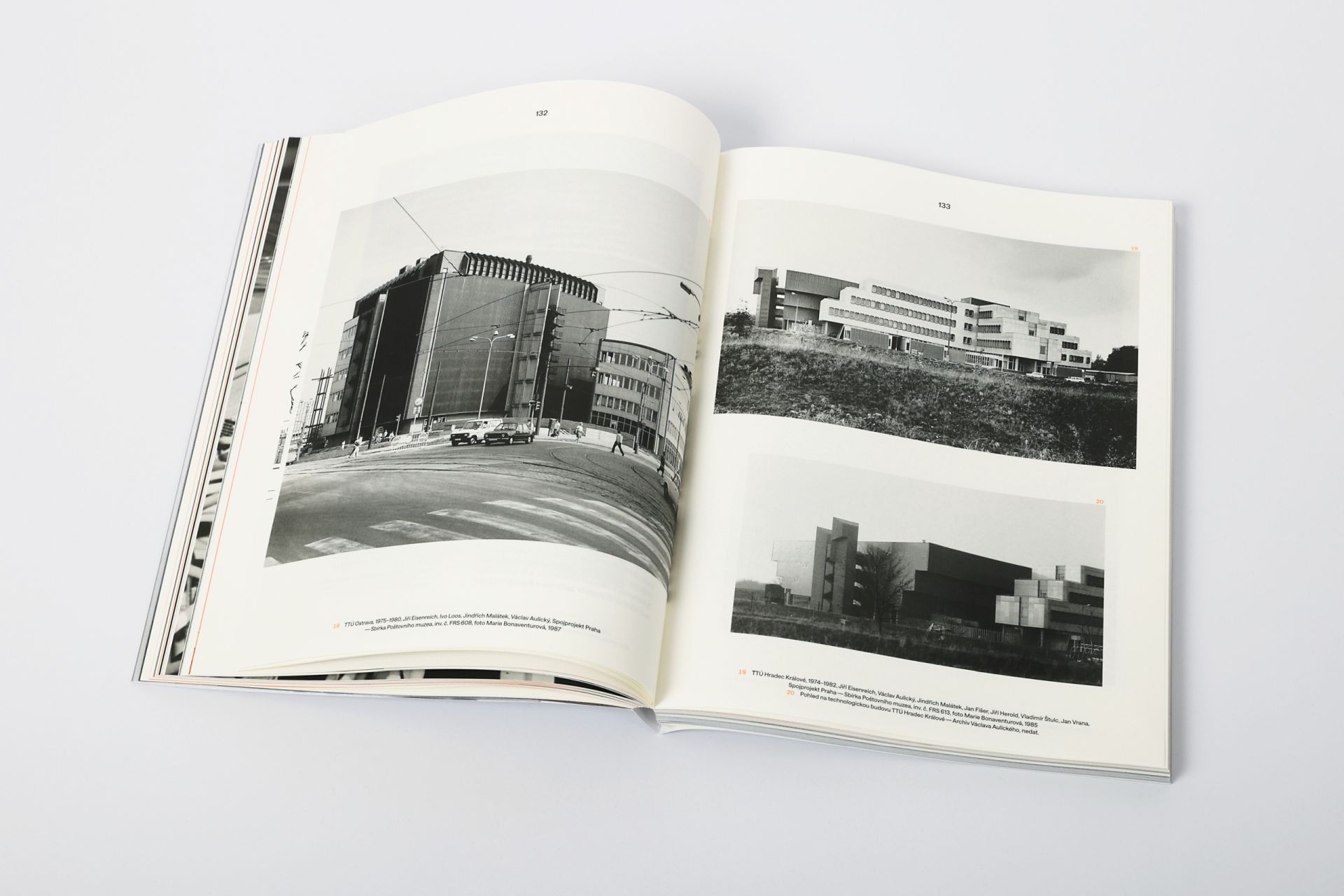

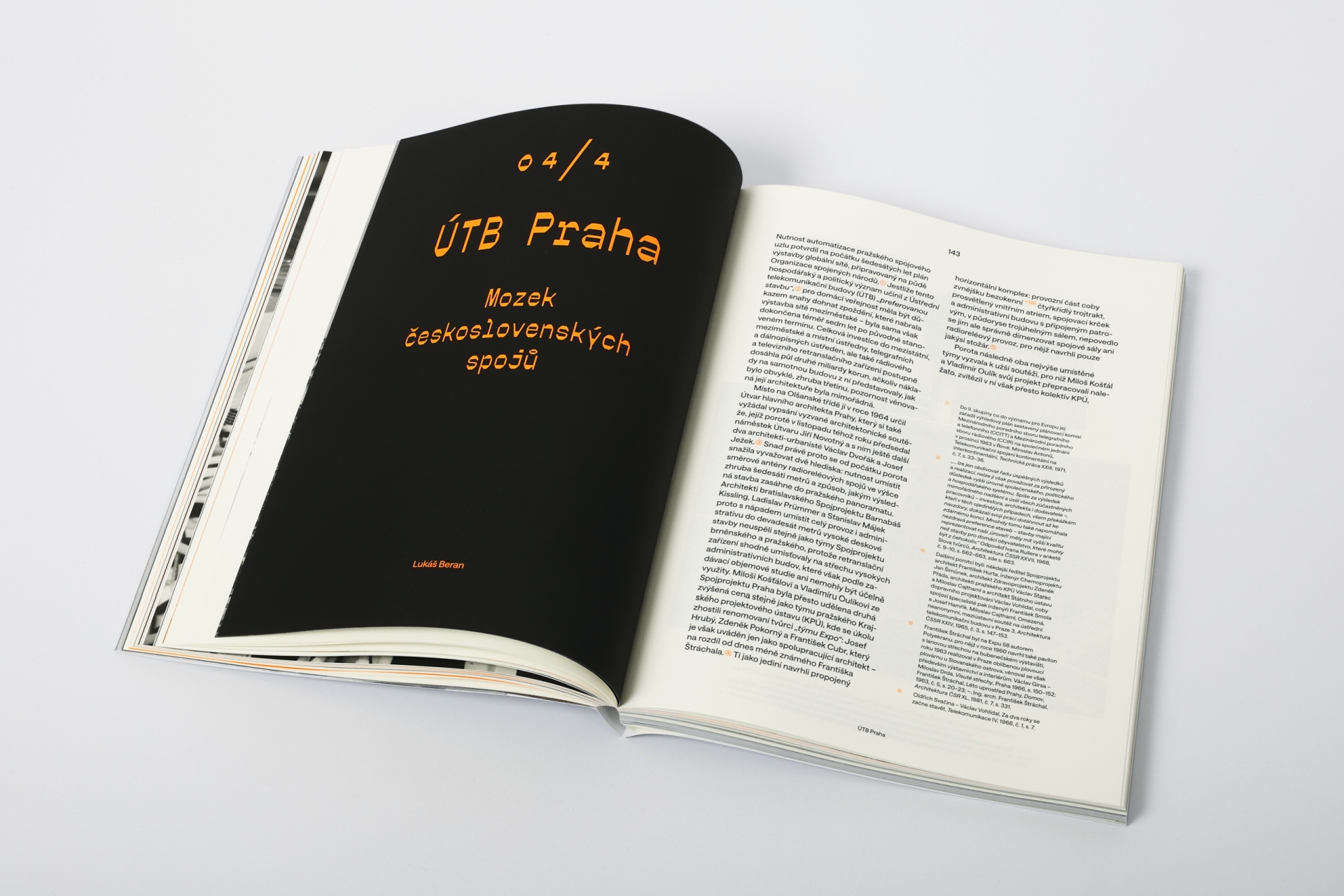

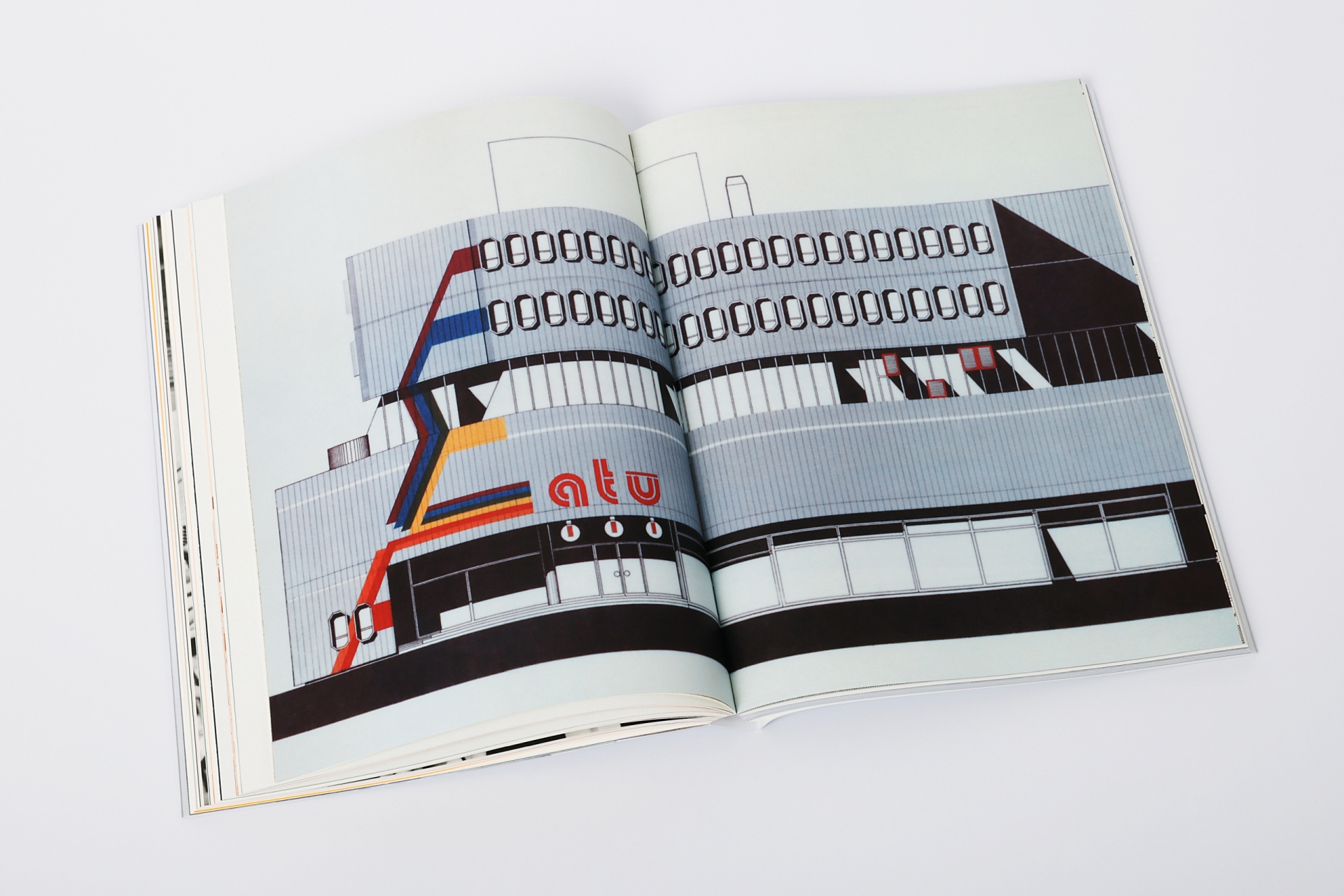

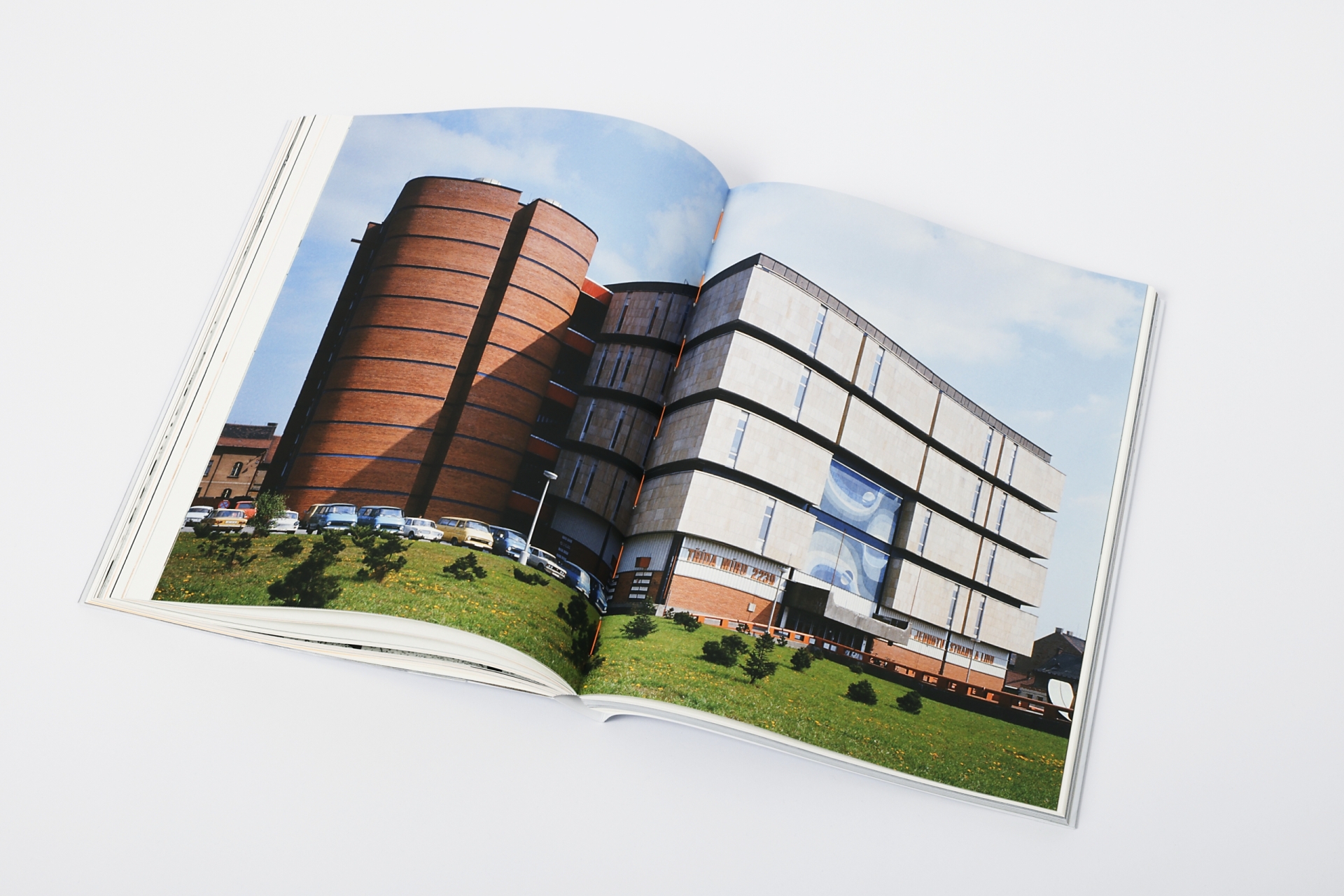

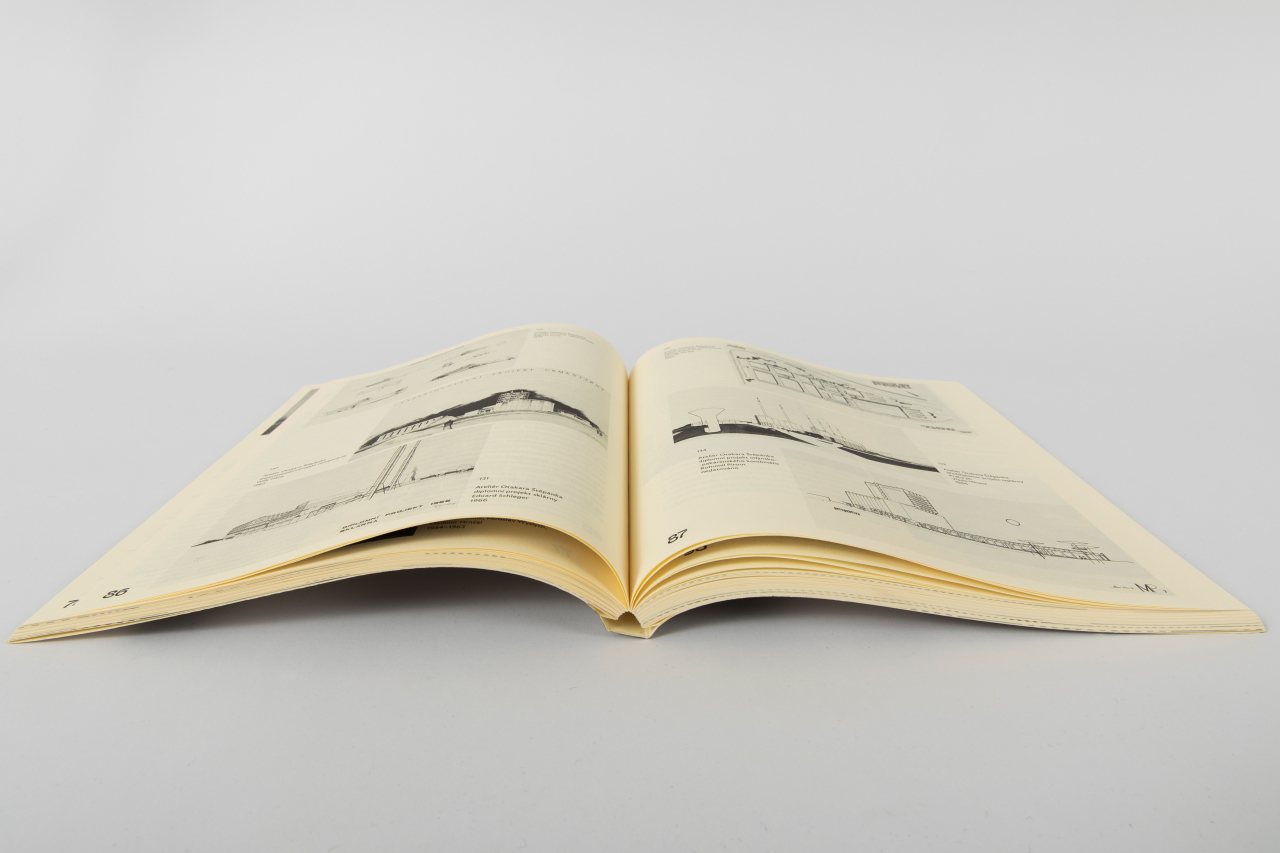

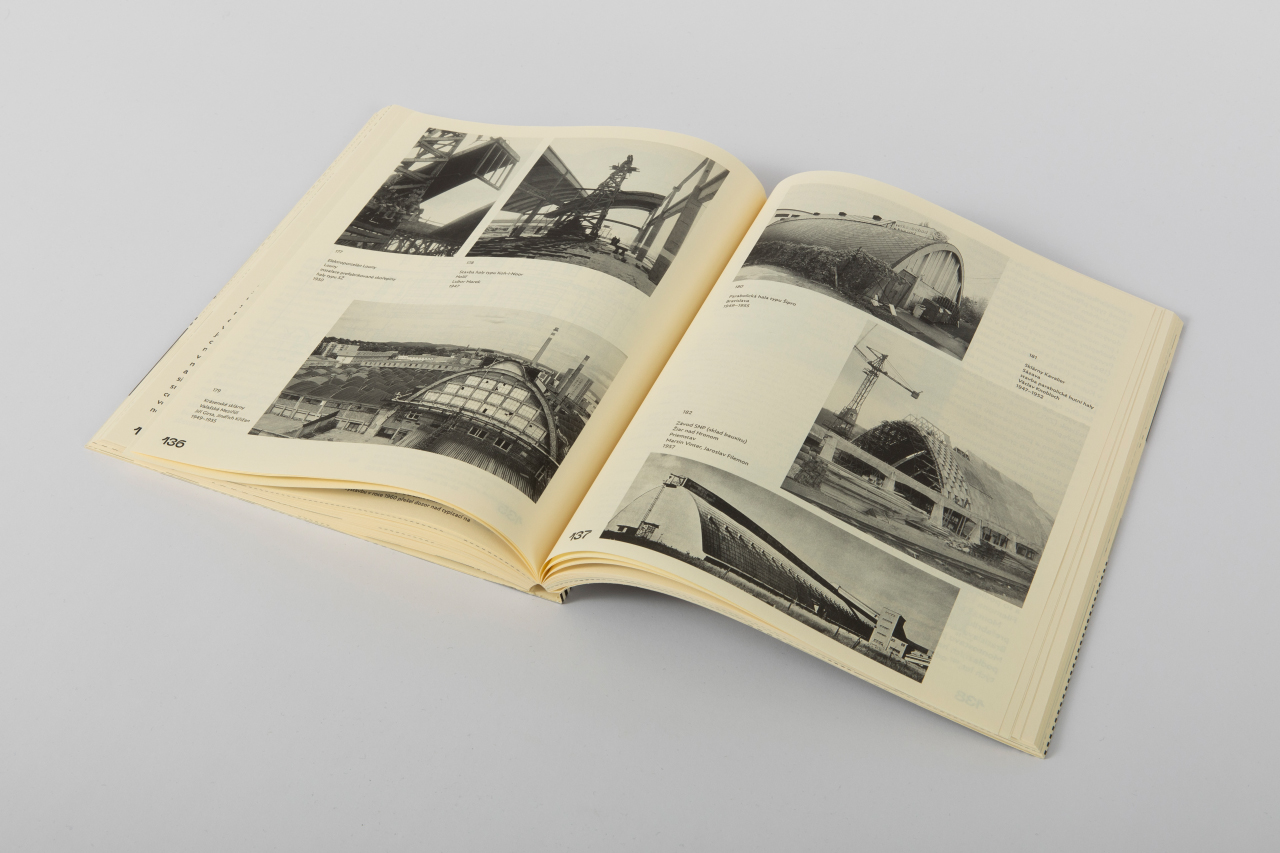

The majority of the book’s space is understandably devoted to architecture. The development of a typology of telephone Exchange buildings after the Second World War is described in detail by Lukáš Beran in his chapter ‘TTÚ/ATÚ/UÚ’, in which he charts the changes to the layout designs, structural solutions, and architectural language of telephone exchange buildings, as well as to their position within the urban plan. Most importantly, he newly identifies many architects behind these buildings and illustrates how a multilayered architecture of telephone exchanges emerged in Czechoslovakia. The most significant of these buildings was the recently demolished Central Telecommunications Building in Prague’s Žižkov district, which is discussed by the same author in a short supplementary appendix titled ‘ÚTB Praha’.

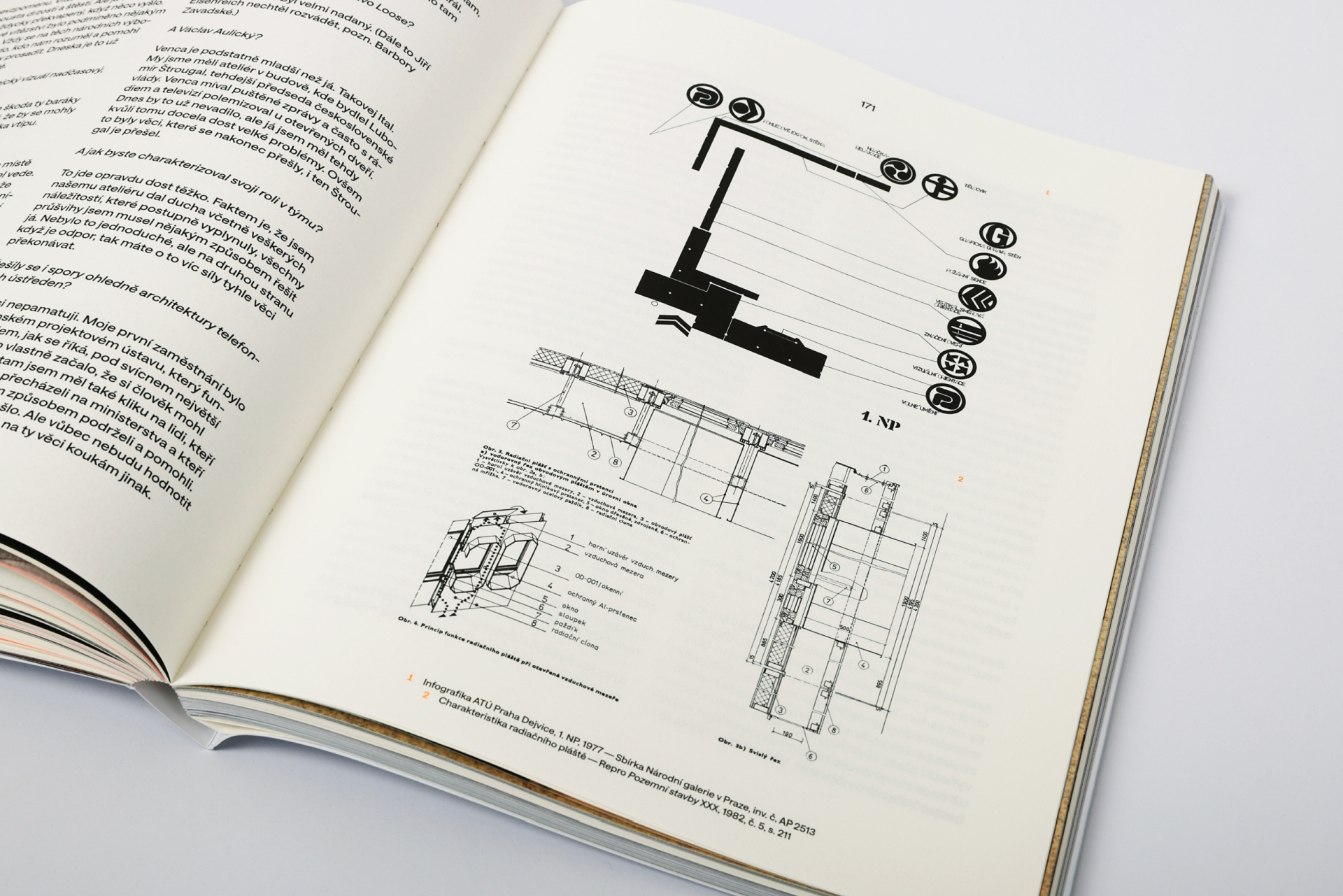

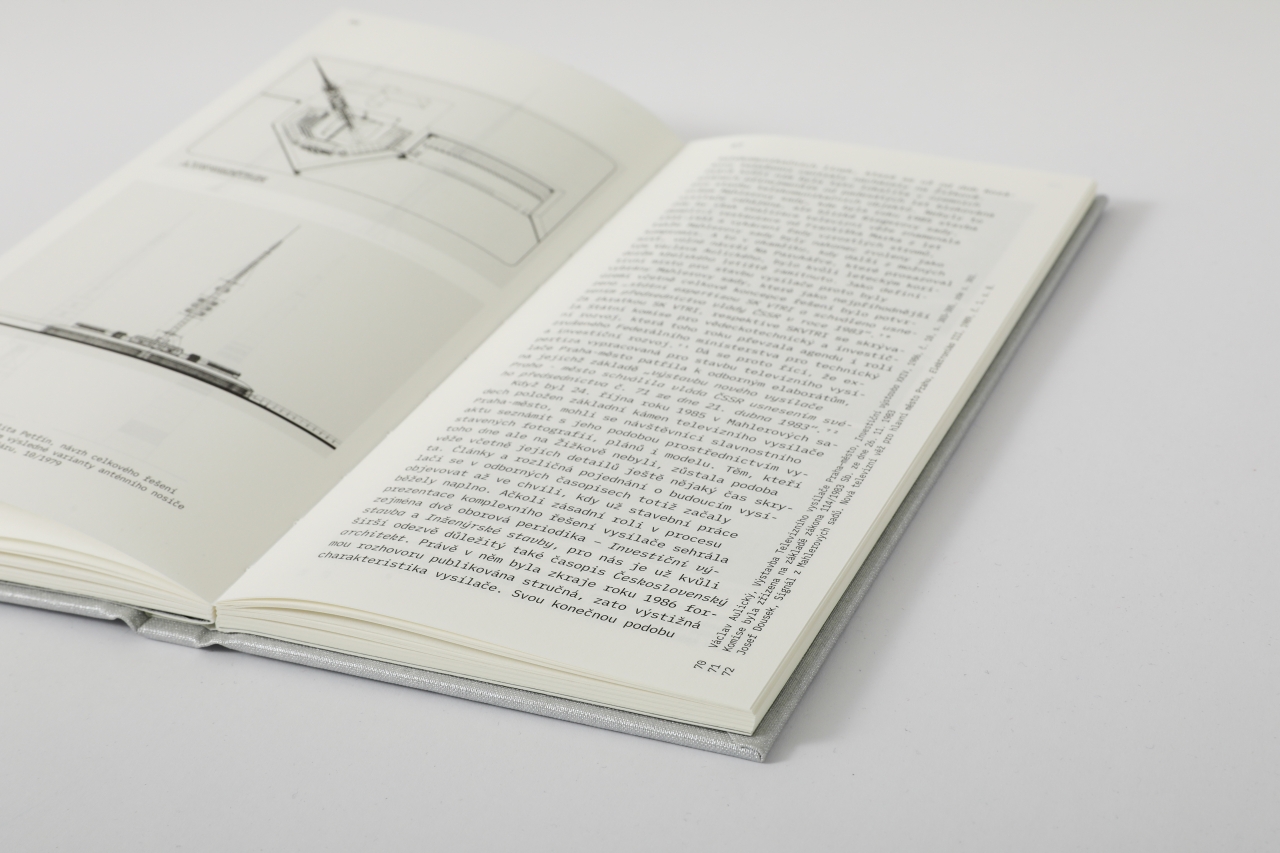

The architectural high point of telephone exchange buildings is represented by the work of Atelier No. 324 of Spojprojekt in Prague: Jiří Eisenreich, Ivo Loos, Jindřich Malátek, Václav Aulický, and Jan Fišer. Barbora Zavadská, in her chapter, notes that their distinctive architecture, which responded to contemporary Western trends and theoretical premises, was made possible by the ability of all the actors to negotiate and improvise within the rigid system of standardised construction they had to work with, as well as by the extremely collegial atmosphere. Zavadská’s chapter ‘Pohled do jednoho ateliéru’ (A Look inside the Atelier) is complemented by interviews she conducted with architects Jiří Eisenreich and Václav Aulický.

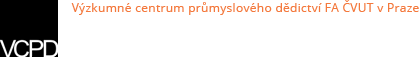

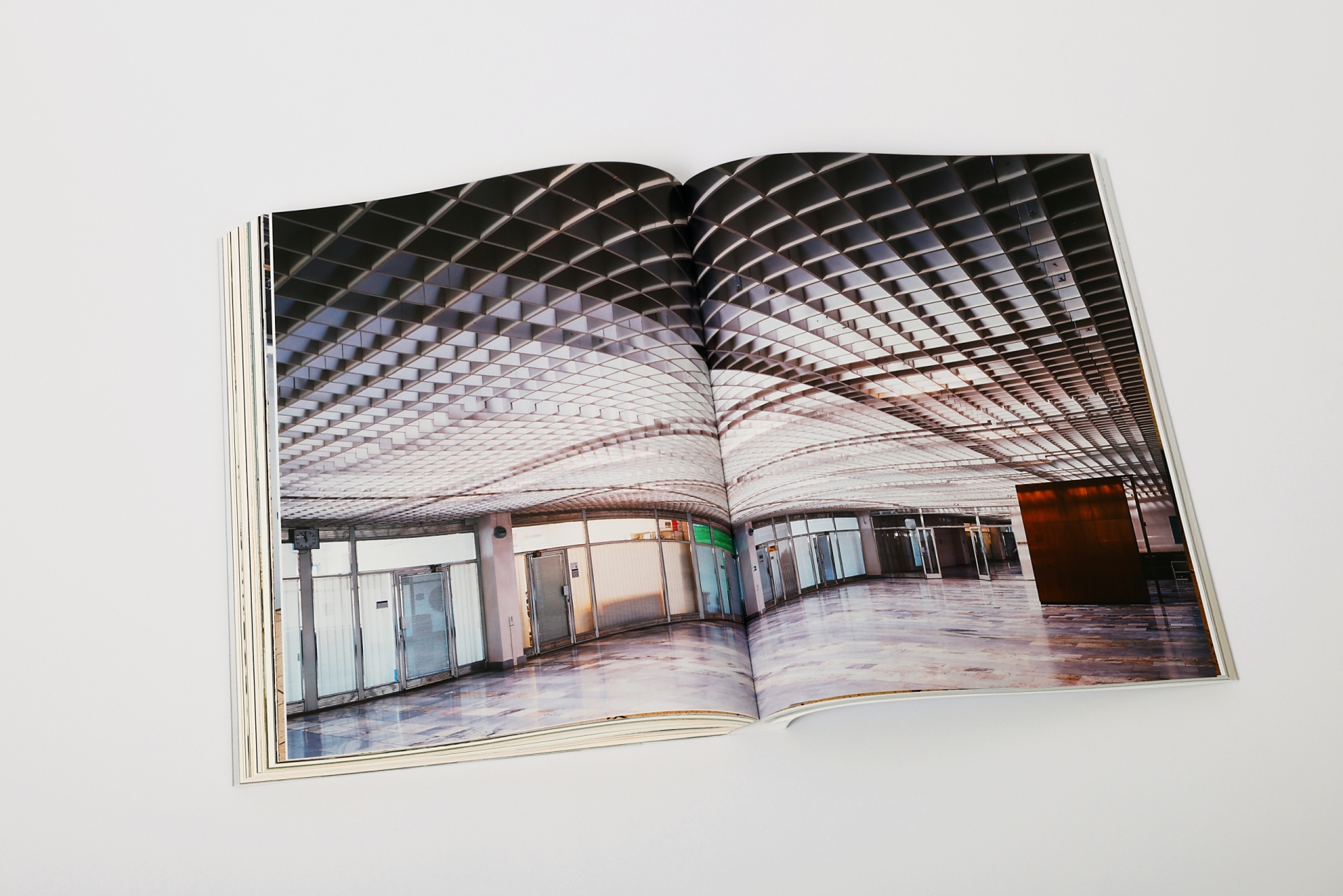

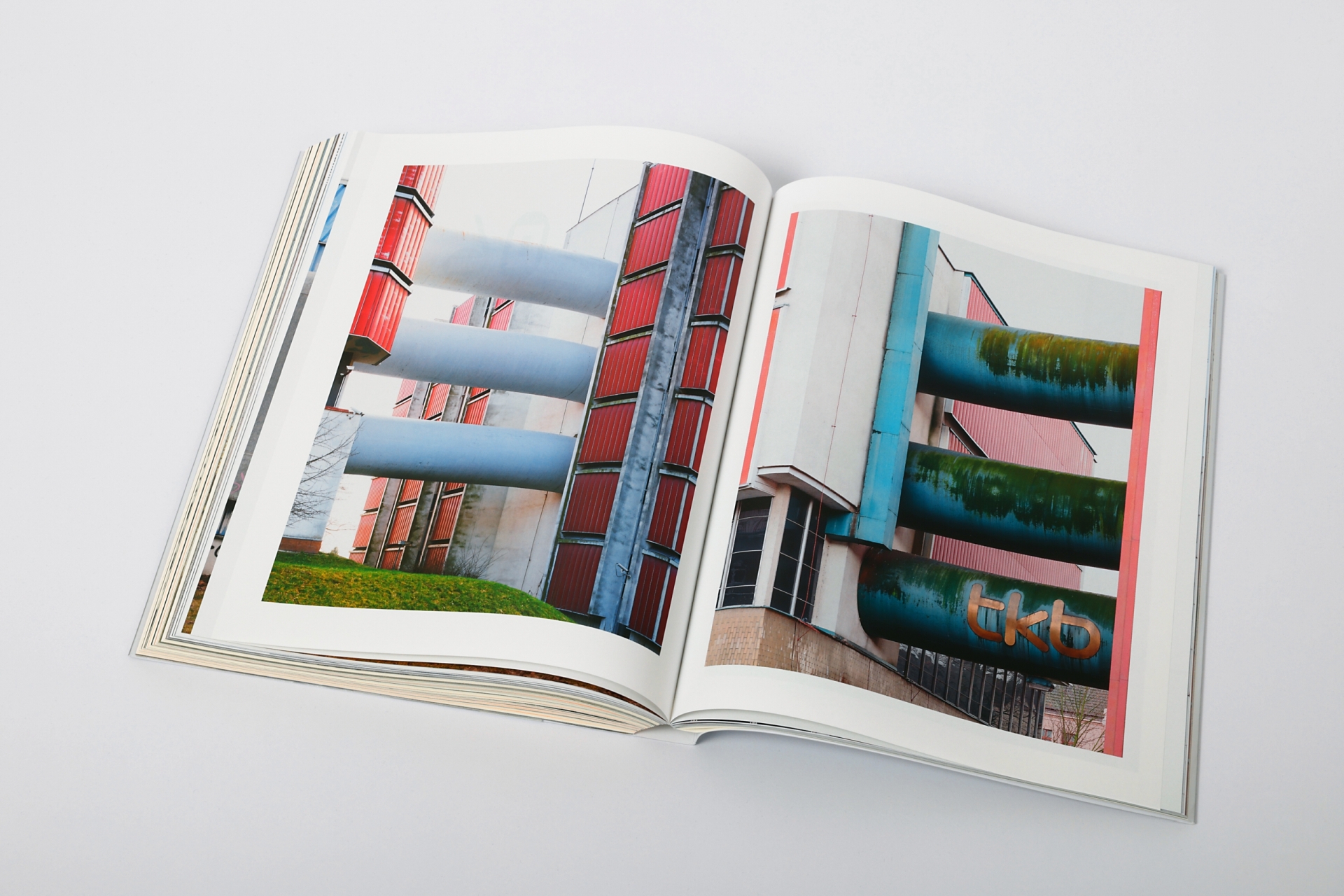

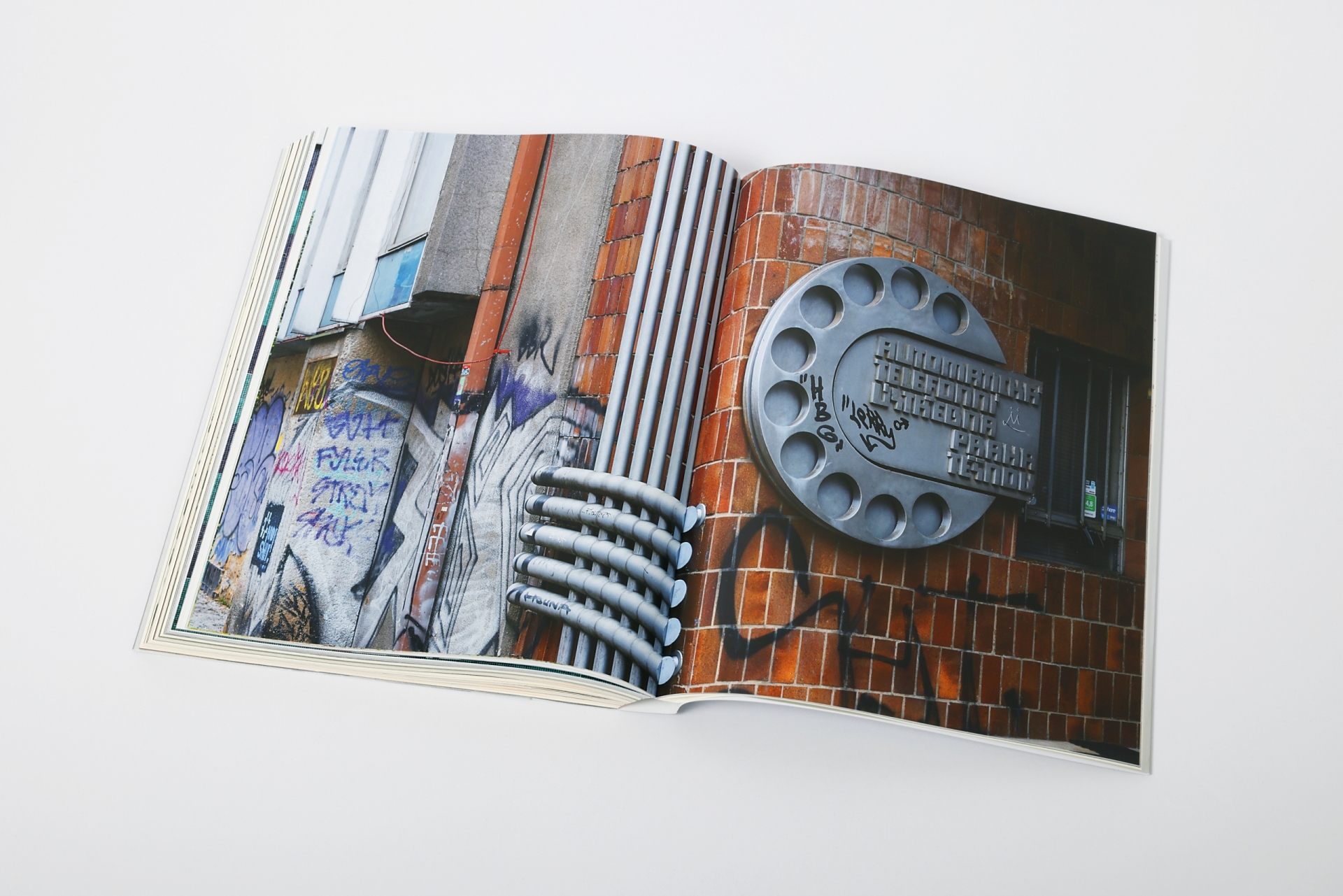

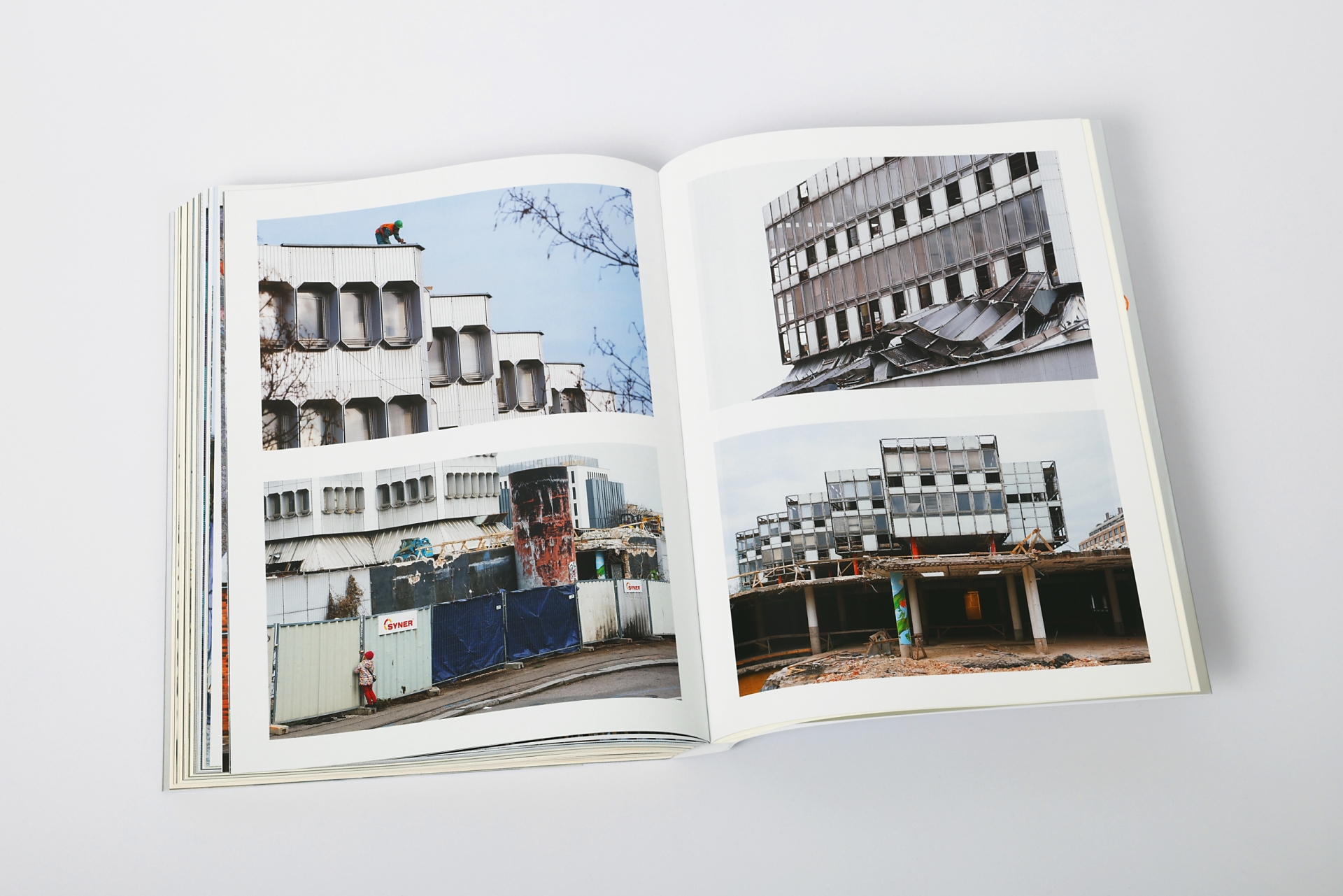

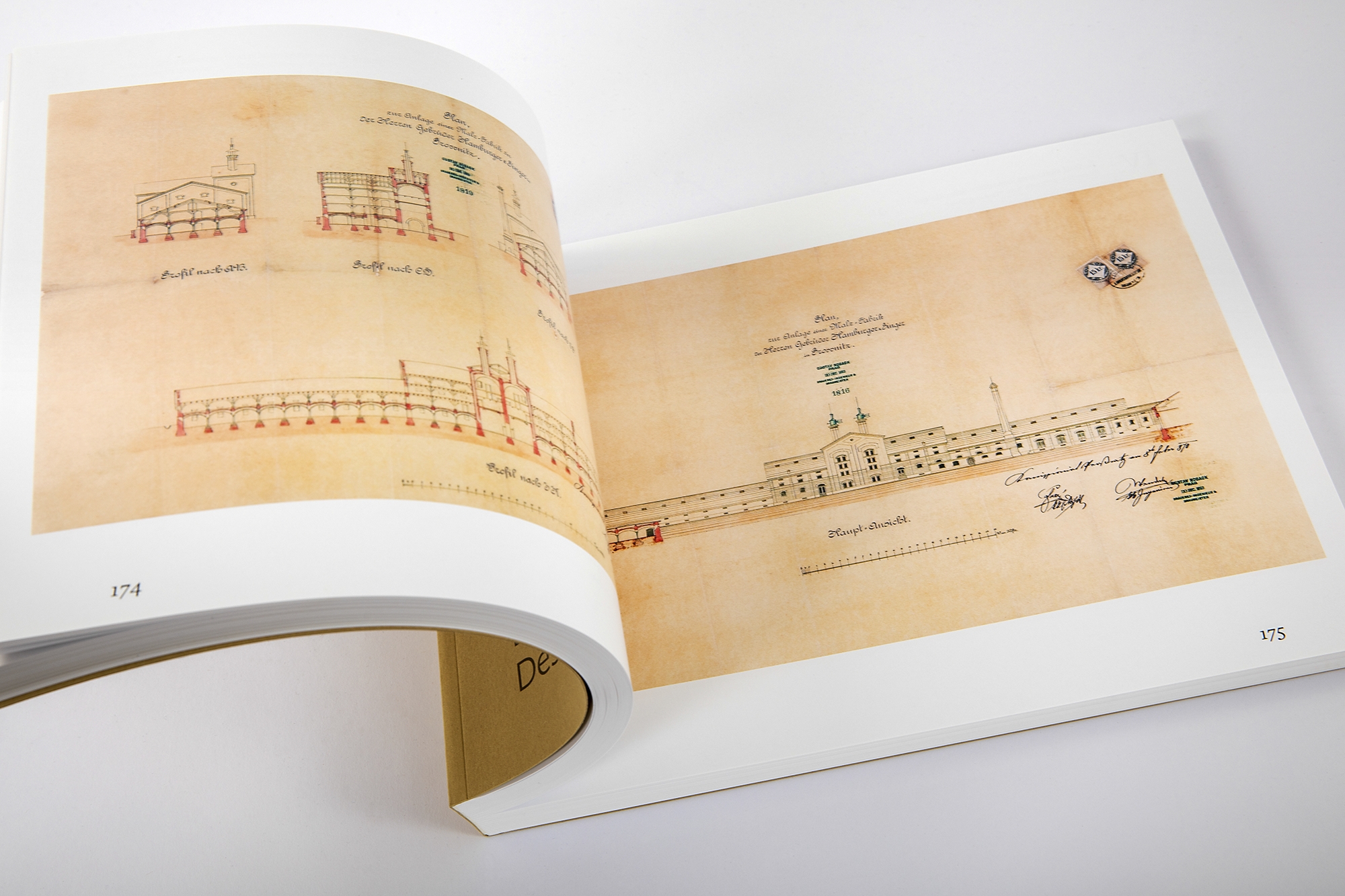

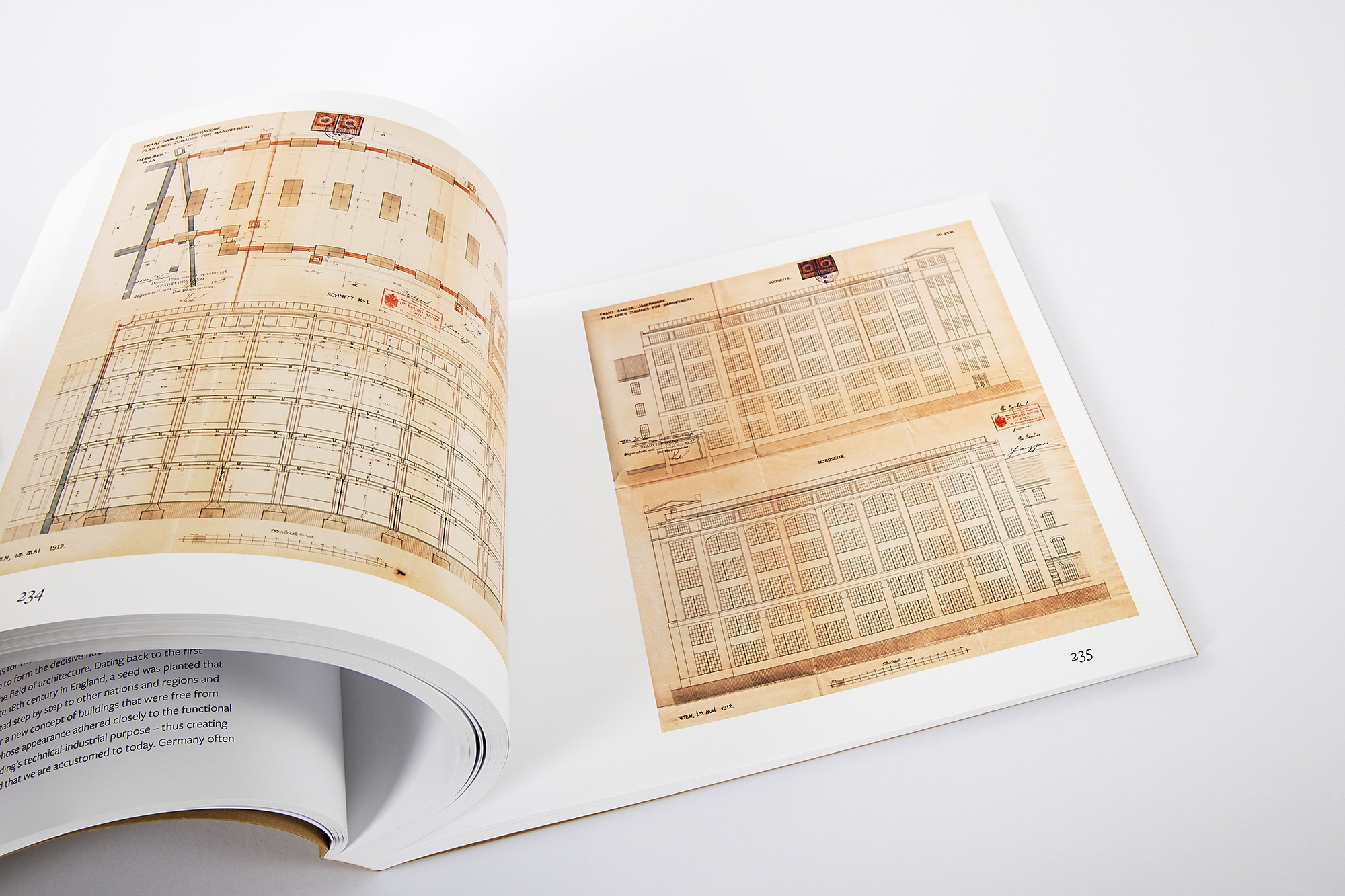

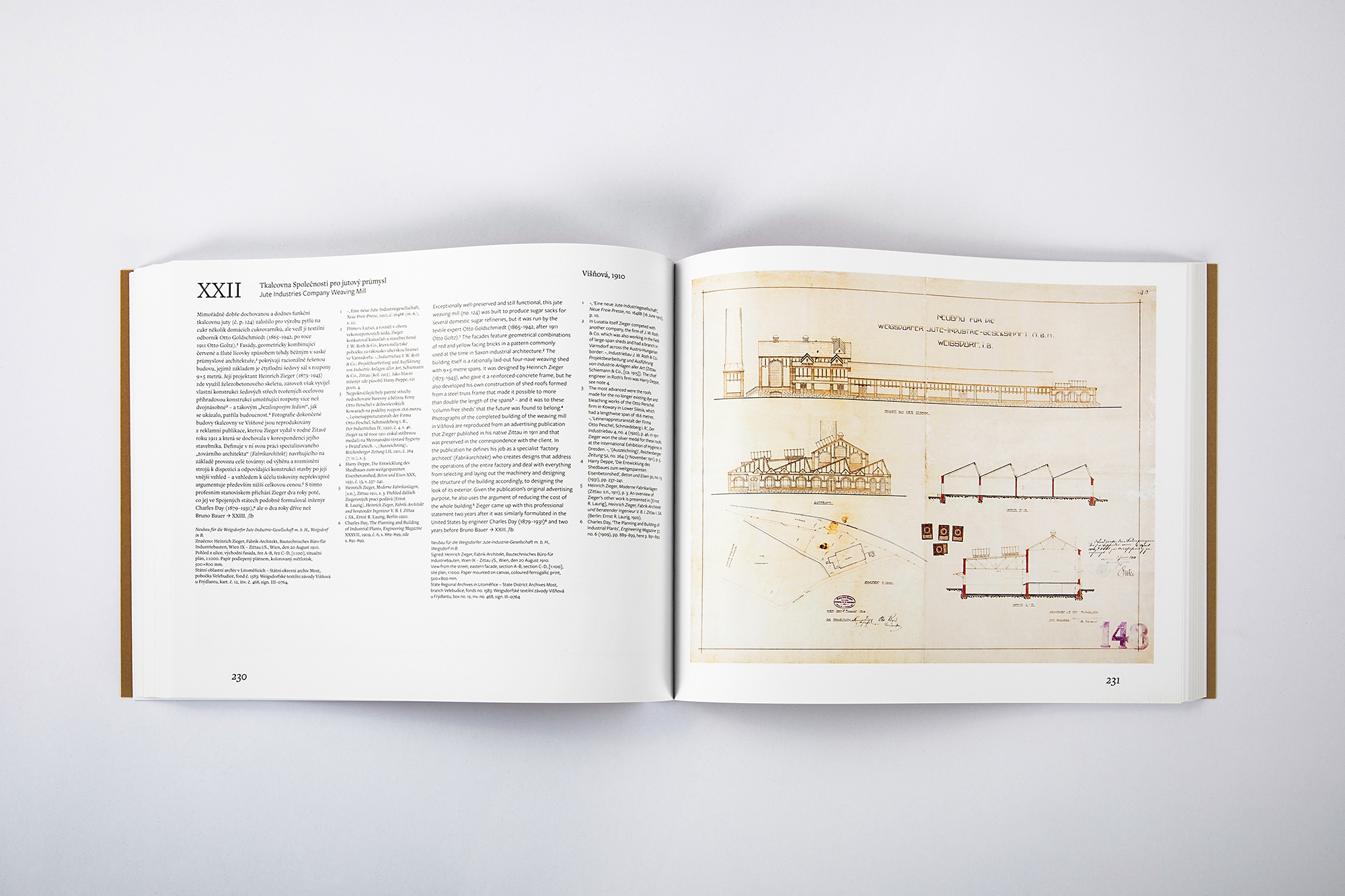

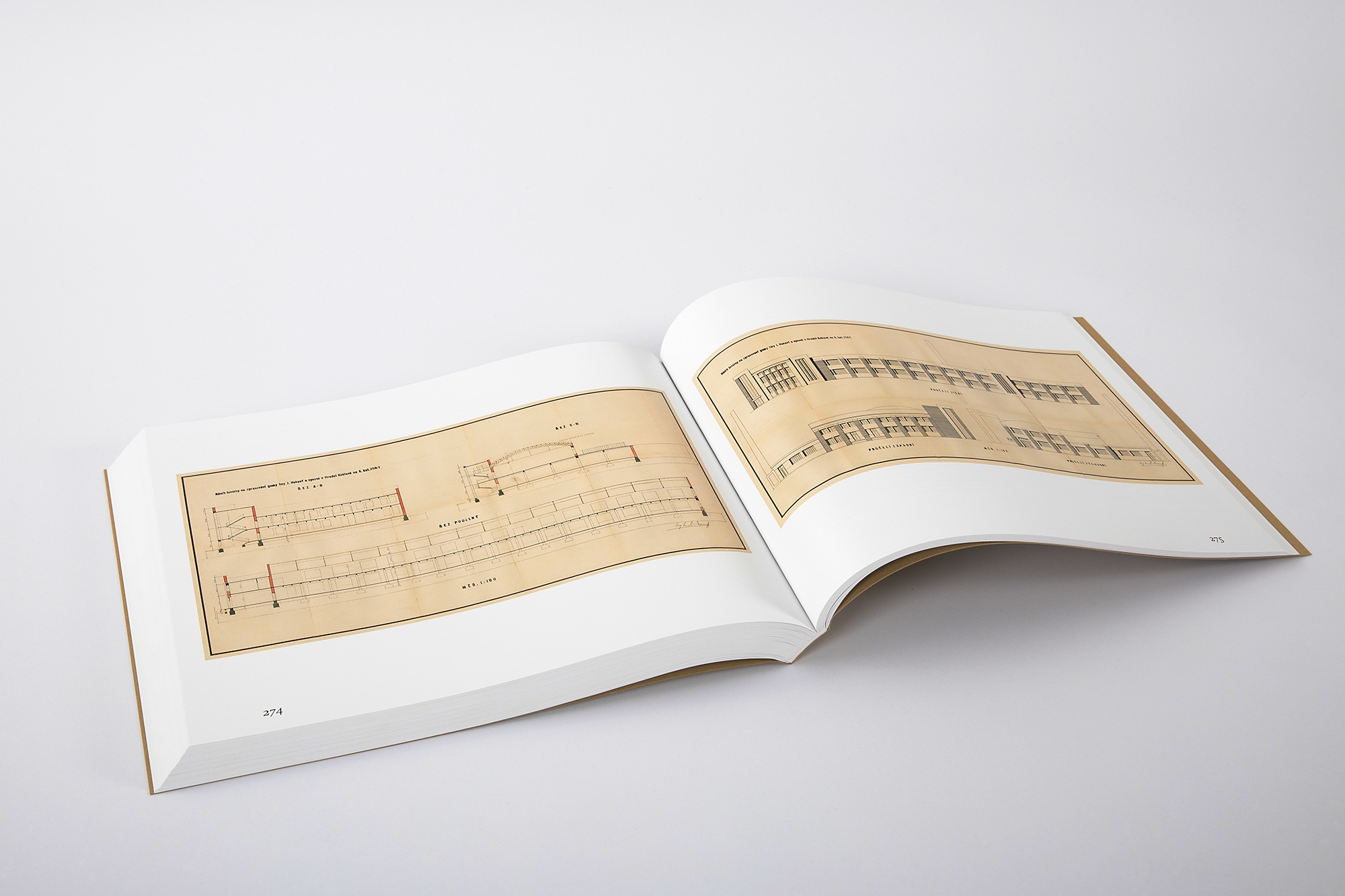

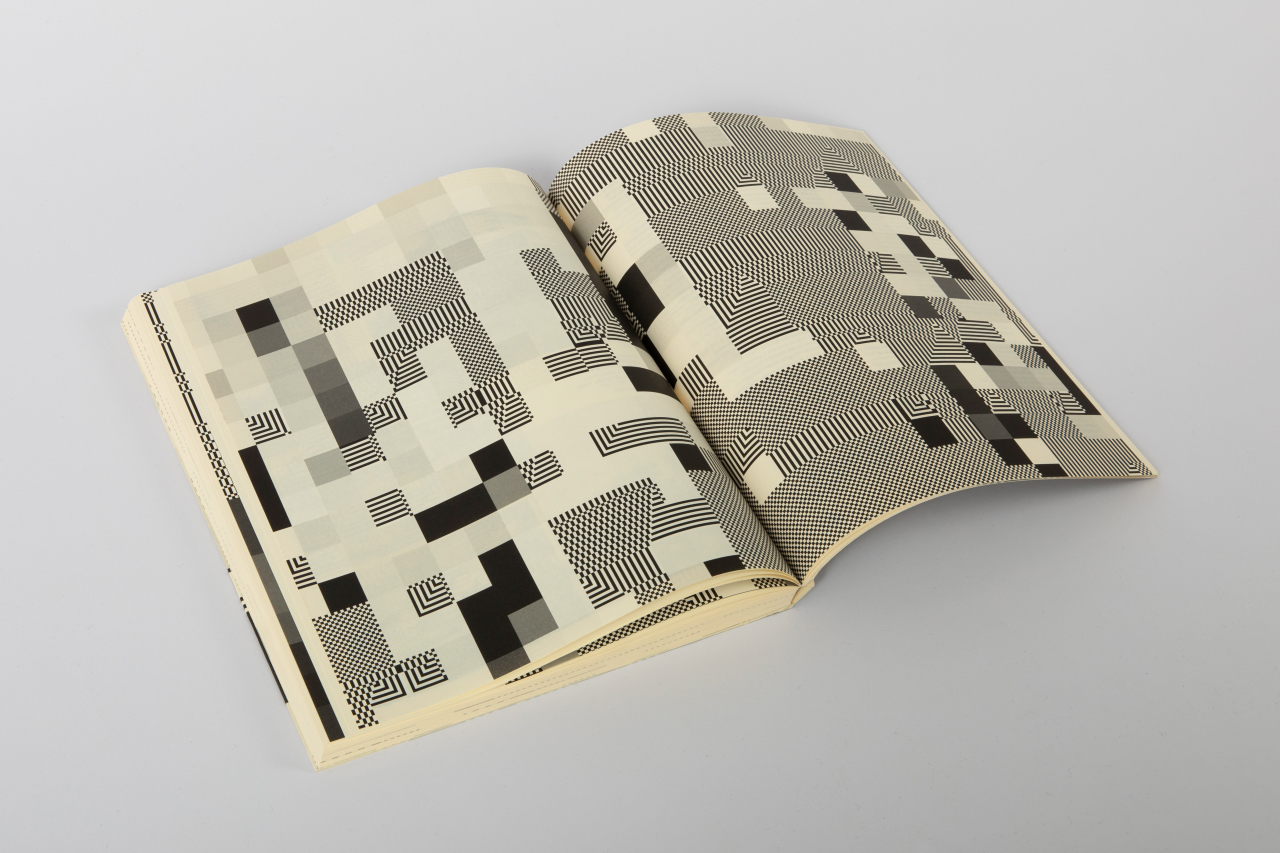

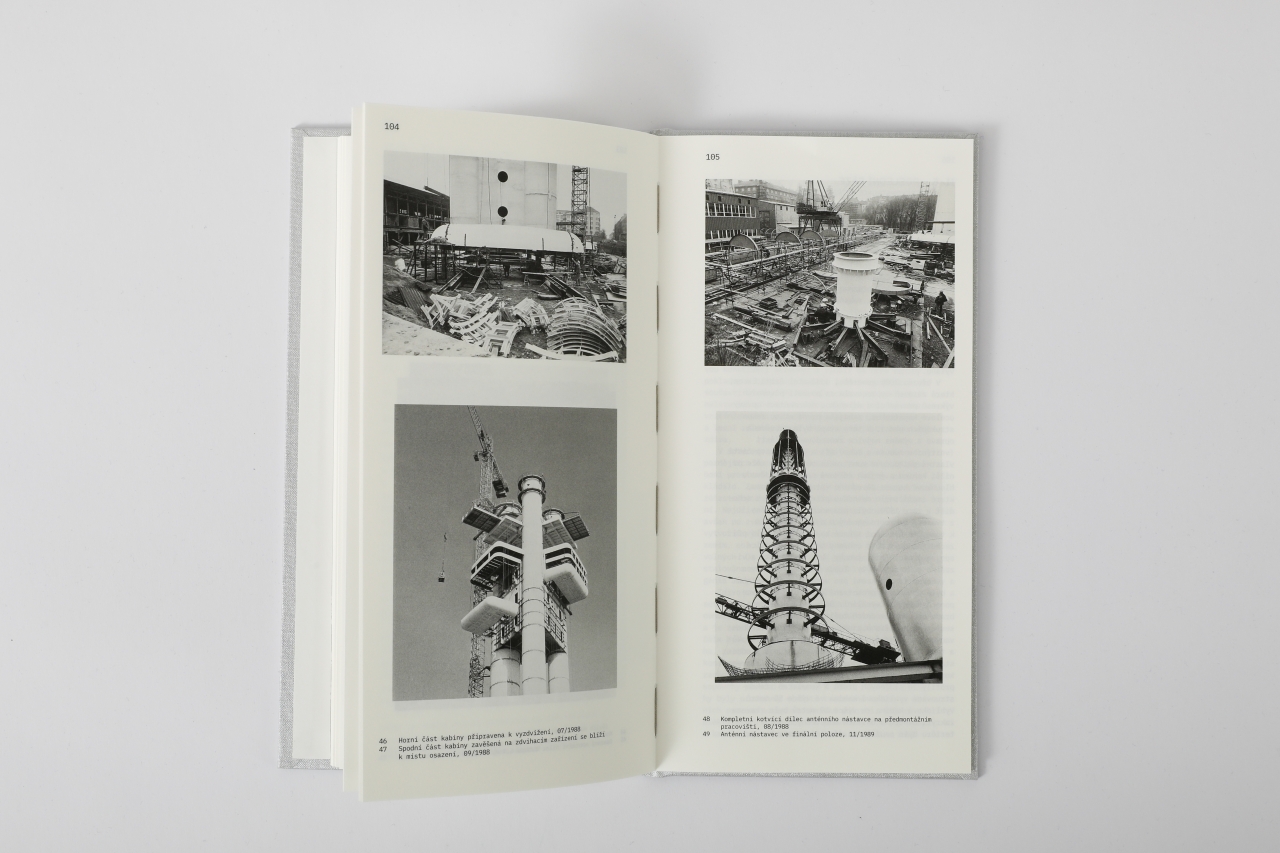

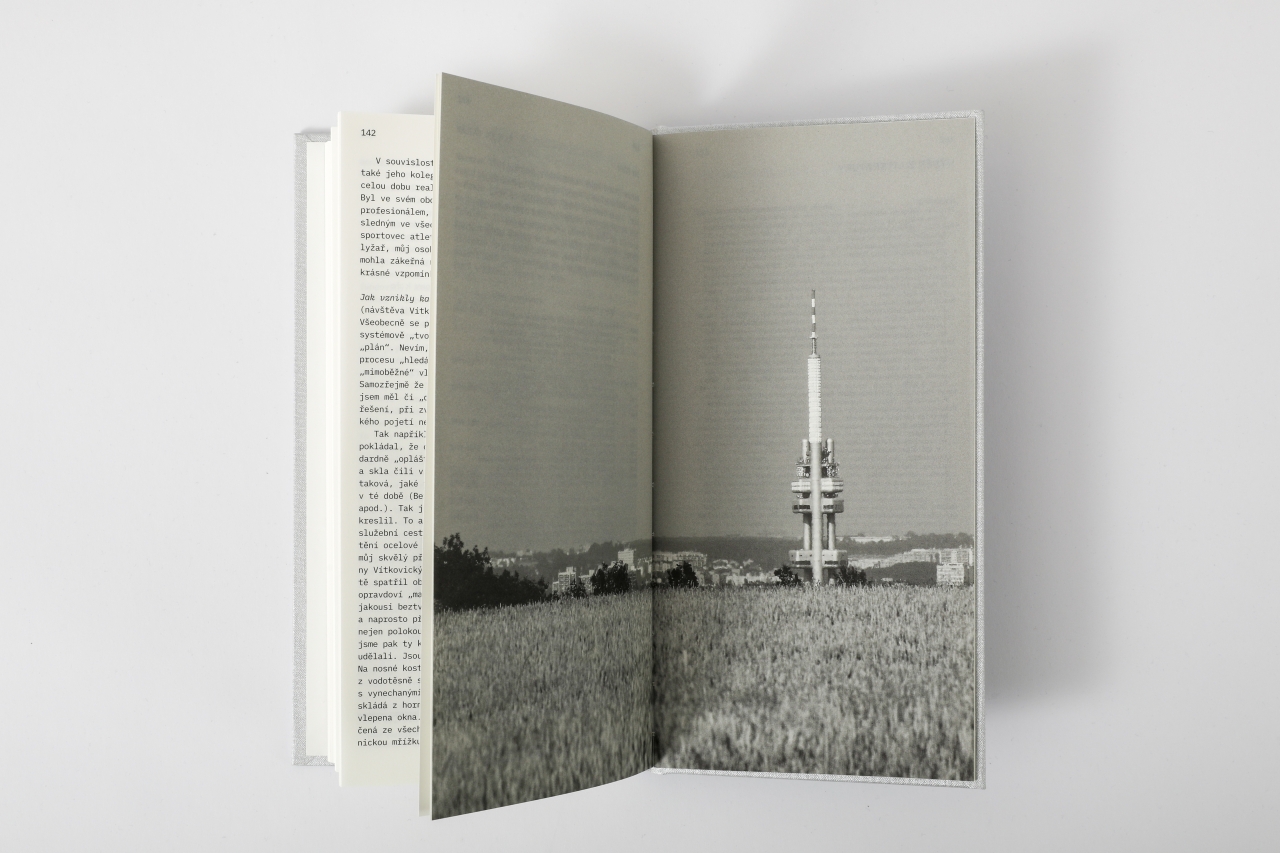

The chapters are accompanied by photographs and plans from the period in question, drawn from the collections of Czech and Slovak museums, galleries, and press agencies, and by many other valuable materials obtained from personal archives. Authentic sources provide the most compelling evidence of the qualities of the subject studied here, but the urgency of its current situation requires an extension of the arguments to the present. The text section of the book therefore concludes with a personal reflection by Petr Freiwillig titled ‘Obětovaná vrstva?’ (The Sacrificed Layer?), in which he asks how Czech heritage conservation reflects the existence of automatic telephone exchanges, and simultaneously he highlights the difficulties involved in recognising the qualities of post-war architecture. In this context, significant space is devoted to visual testimony. A photographic essay by Viktor Macha captures liminal moments in the disappearance of the evidence of what until recently were the most progressive achievements ever to be made in architecture, technological development, and the professional environment of Czechoslovak institutions. Many of the sites in these photographs have been lost since they were taken. Viktor Mácha is thus also recording the speed at which we are losing a layer of our history.

This book is the first publication output of a project supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic under the National and Cultural Identity (NAKI III) research and development programme: ‘Industrial Architecture in the Second Half of the 20th Century: Extension, Transformation, and Identity’. As an auxiliary aktivity with practical applications, the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage organised a workshop for students of the Faculty of Architecture of the Czech Technical University in the spring of 2024 with the aim of finding new uses for the automatic telephone exchanges located in Těšnov and Řepy in Prague. The results of the workshop were presented in the autumn in an exhibition and a small publication, which is available for download at: zavodyprumyslu.cz. None of the eleven projects foresaw the destruction that now awaits the exchange in Těšnov, and the exchange in the Řepy housing estate will probably meet the same fate. The students’ work demonstrated that introducing a topic, defining a problem, and formulating a solution can lead to outcomes other than demolition. With the same motivation, this book hopes to join the discussion in society about the future of automatic telephone exchanges.

Book review: Eva Belláková, Architecture Answers the Call: Typology, Technology, and Memory, Architektúra & urbanizmus LIX, 2025, no. 1–2, pp. 190–192 (available here).

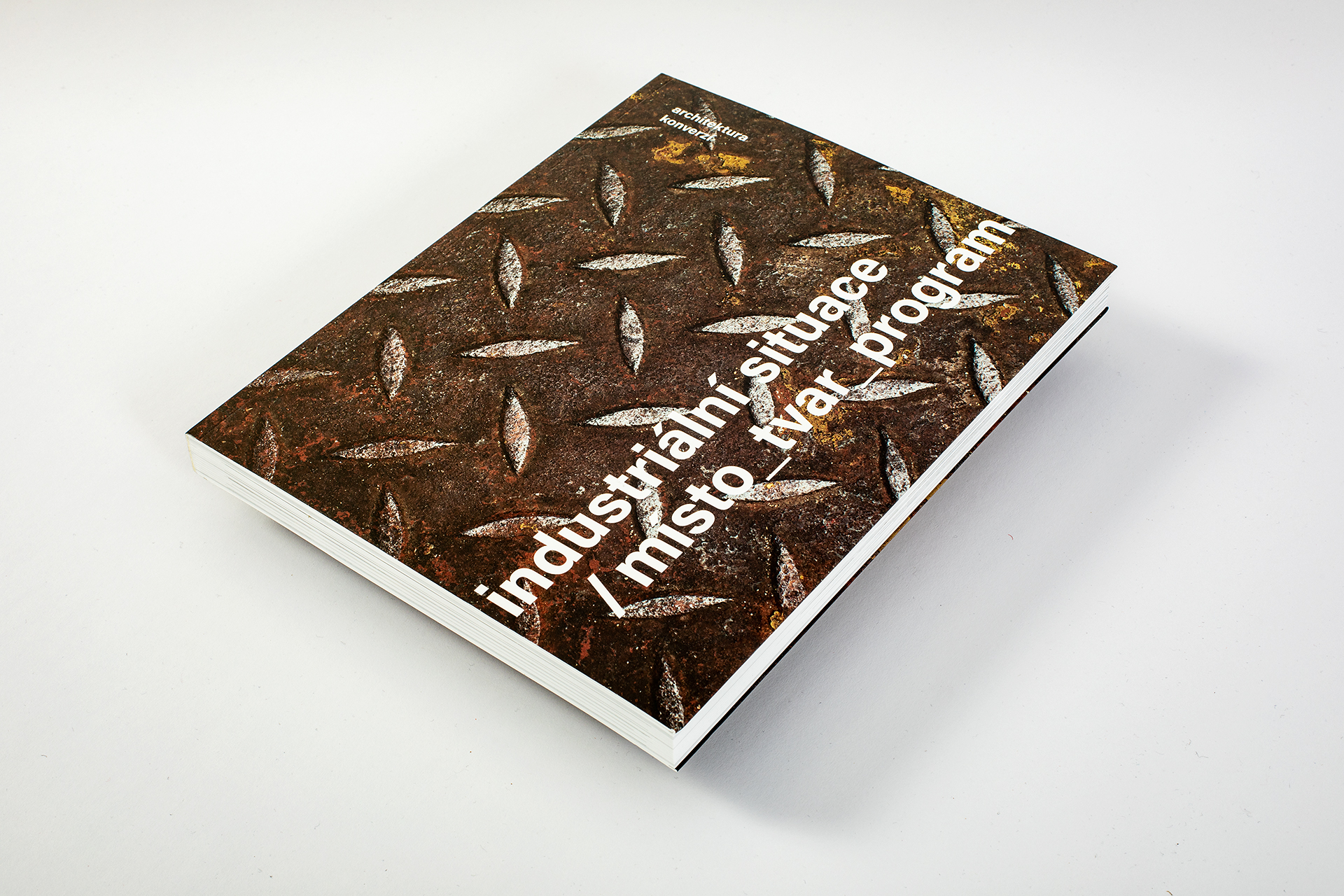

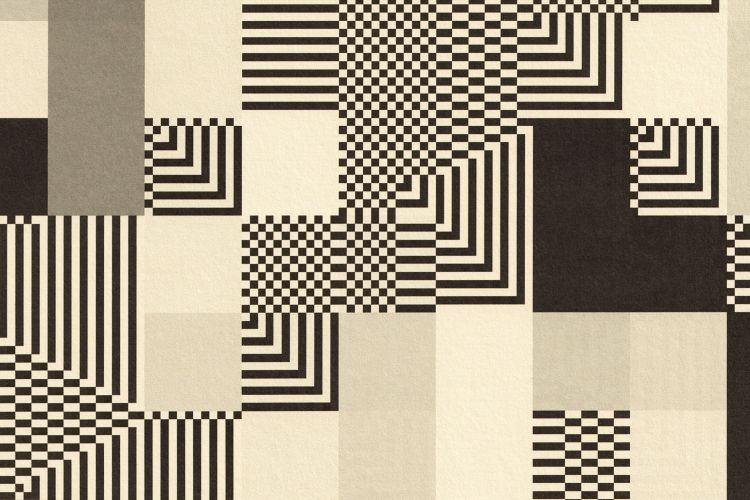

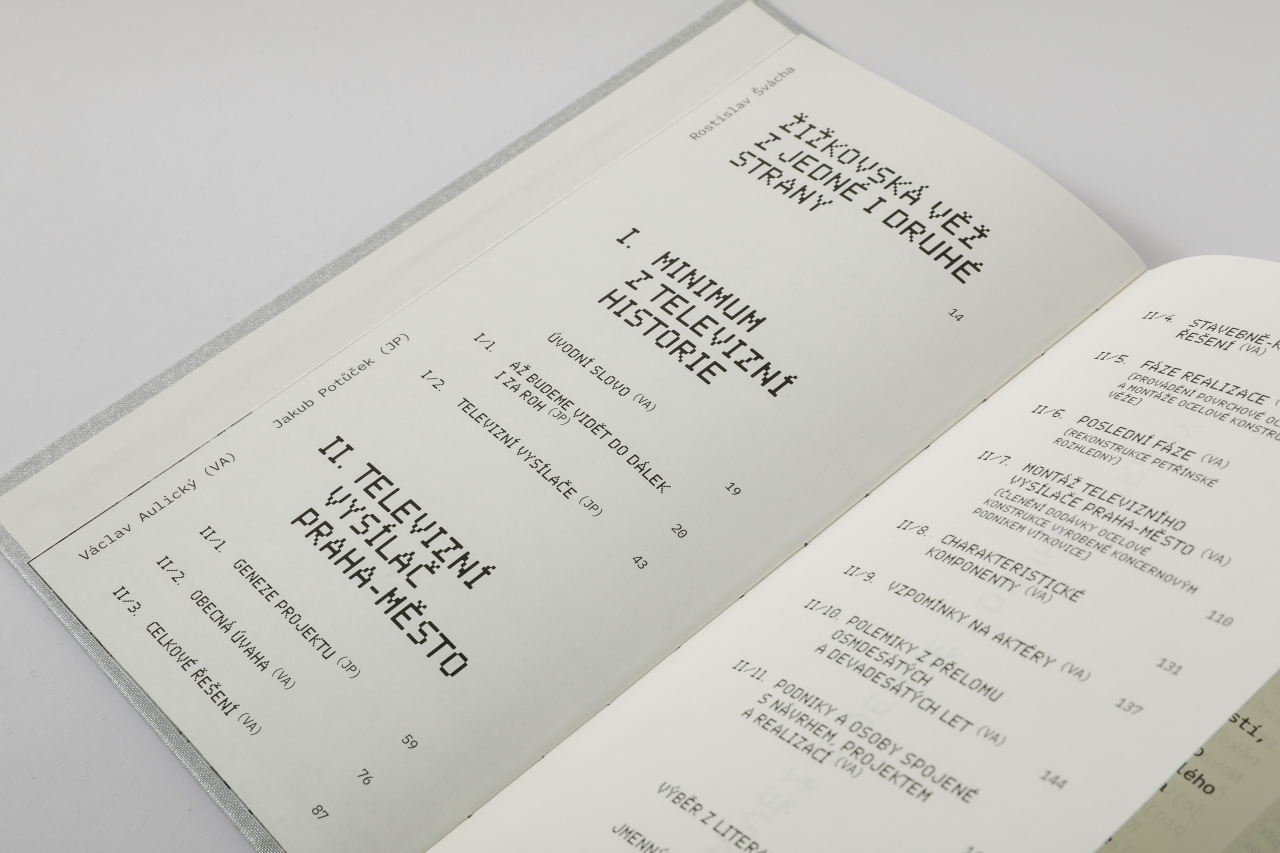

ATÚ: Automatic Telephone Exchanges: Society, Technology, Architecture | 360 pages; in Czech, summary in English; 304 colour a b/w reproductions; ISBN 978-80-01-07322-3 | Editors: Irena Lehkoživová, Jan Zikmund | Authors: Lukáš Beran, Benjamin Fragner, Petr Freiwillig, Irena Lehkoživová, Jakub Potůček, Jiří Suchomel, Barbora Zavadská, Jan Zikmund | Photographic essay: Viktor Mácha | Cooperation: Václav Aulický, Tereza Bartošíková, Jan Červinka | Scientific reviewers: Michaela Janečková, Peter Szalay | Copy editing: Irena Hlinková | Translation: Robin Cassling | Graphic design: Formall | Treatment of reproductions: Jiří Klíma | Fonts: 2049 (Off Type), Saans (Displaay) | Materials: Munken Pure Rough 100 g, Chorus Lux Gloss 115 g, Profisilk 400 g | Production: Gabriel Fragner | Print: Tiskárna Helbich | Published by the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage FA CTU Prague

photos Gabriel Fragner