1898–1921

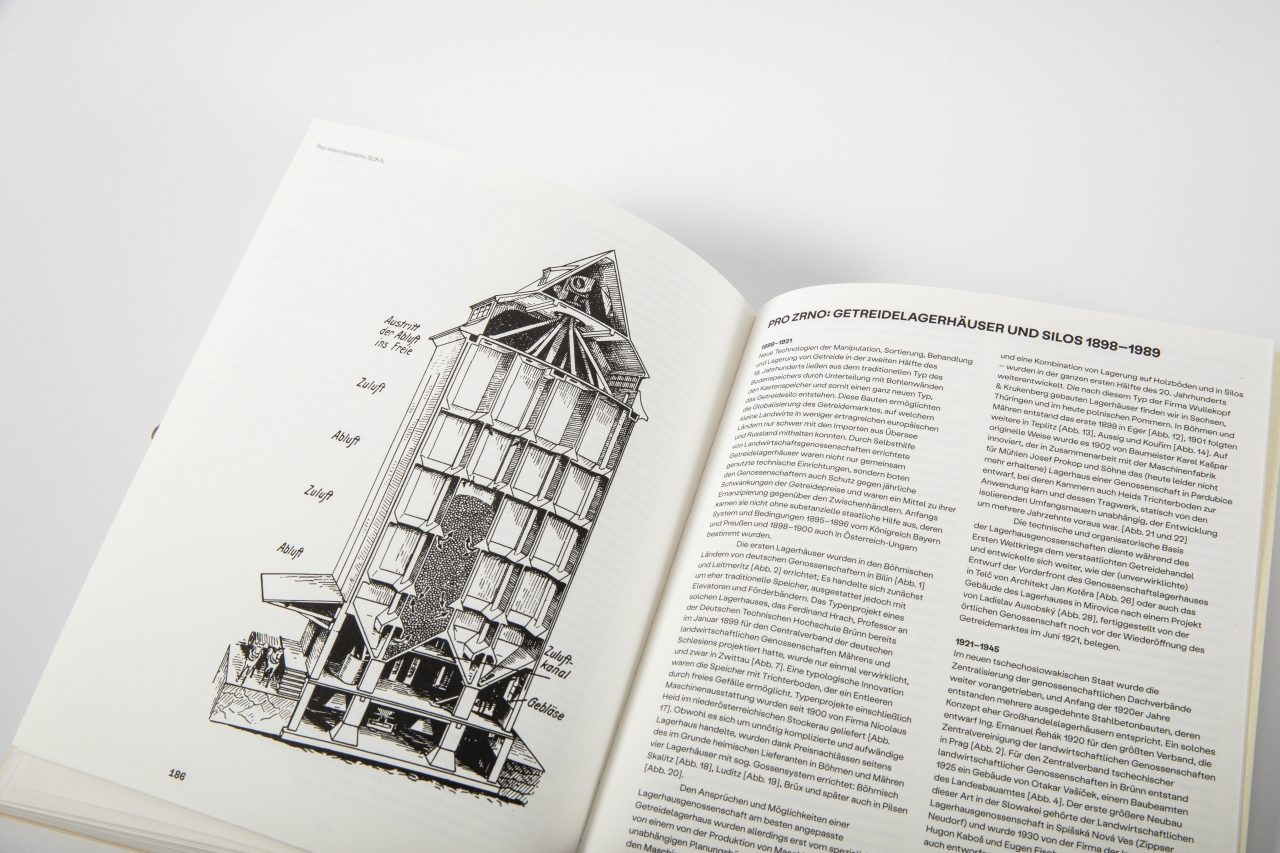

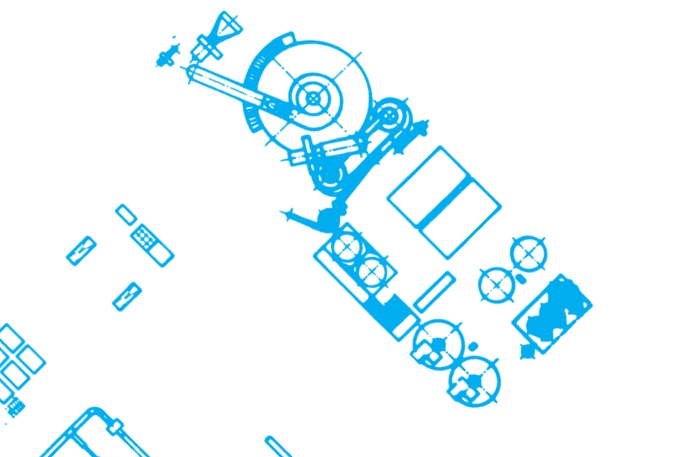

The new technologies that emerged in the second half of the 19th century to move, sort, treat, and store grain transformed the traditional model of floor granary building by dividing it up with plank walls to create shallow bins, but they also gave rise to a brand new type of structure – the grain silo, consisting entirely of deep bins. These structures helped bring about the globalisation of the grain market, in which small farmers in the less fertile countries of Europe then had a hard time competing with imports from overseas and Russia. Grain stores were built by agricultural cooperatives themselves, and not only were they shared technical facilities, they also served as a way of protecting members of a cooperative against seasonal fluctuations in grain prices and of freeing them from dependence on middlemen. Initially they operated with financial support from the state, and the system and conditions that made this possible were created in the Bavarian and Prussian Kingdoms in 1895–1896 and in Austria-Hungary in 1898–1900.

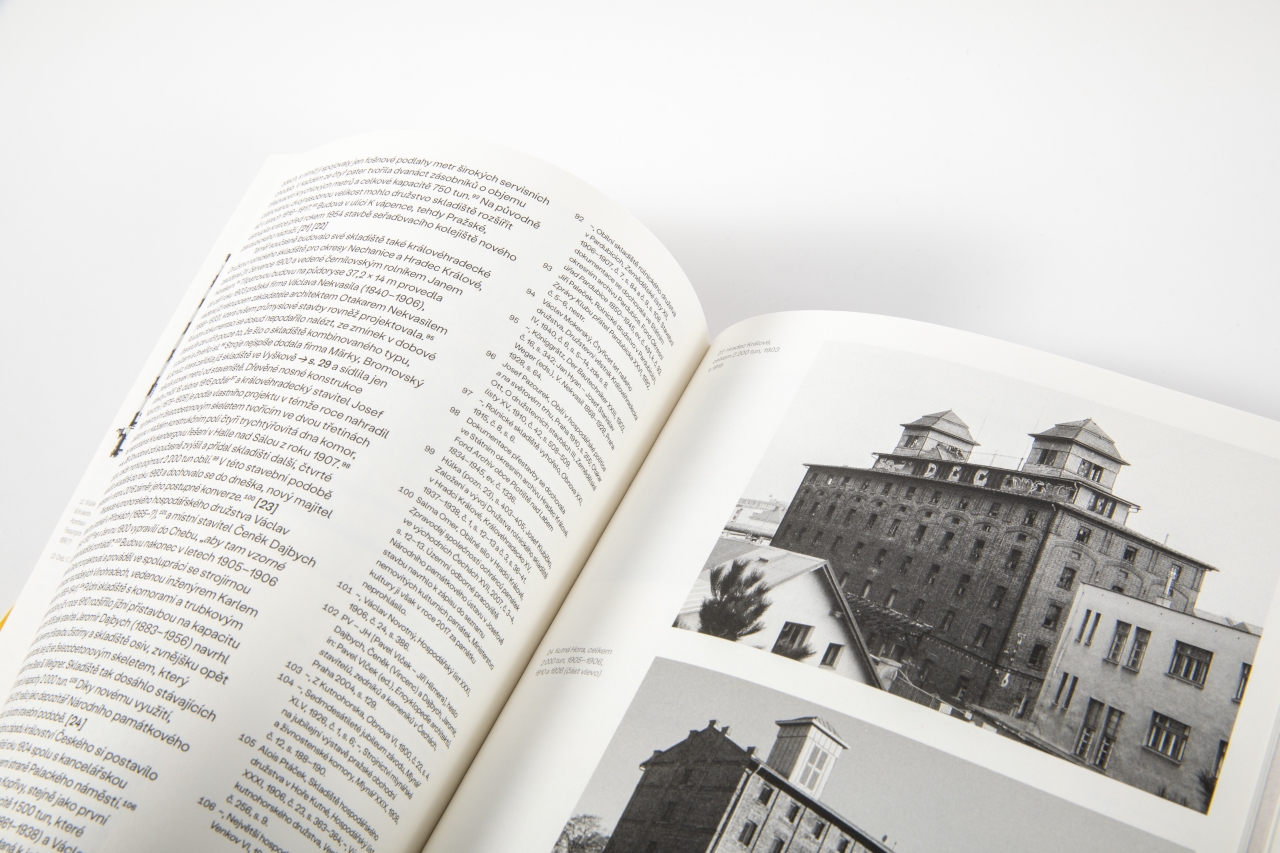

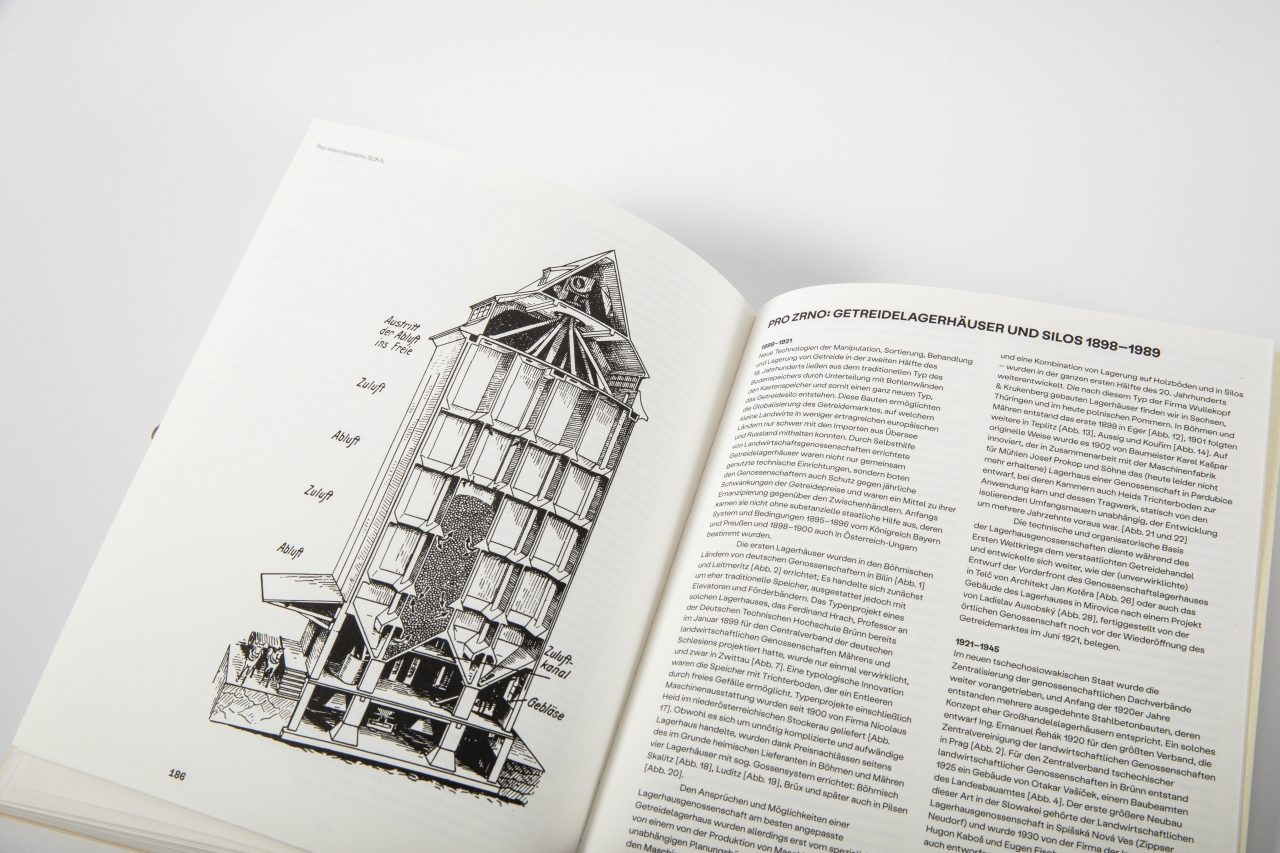

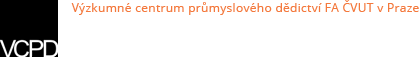

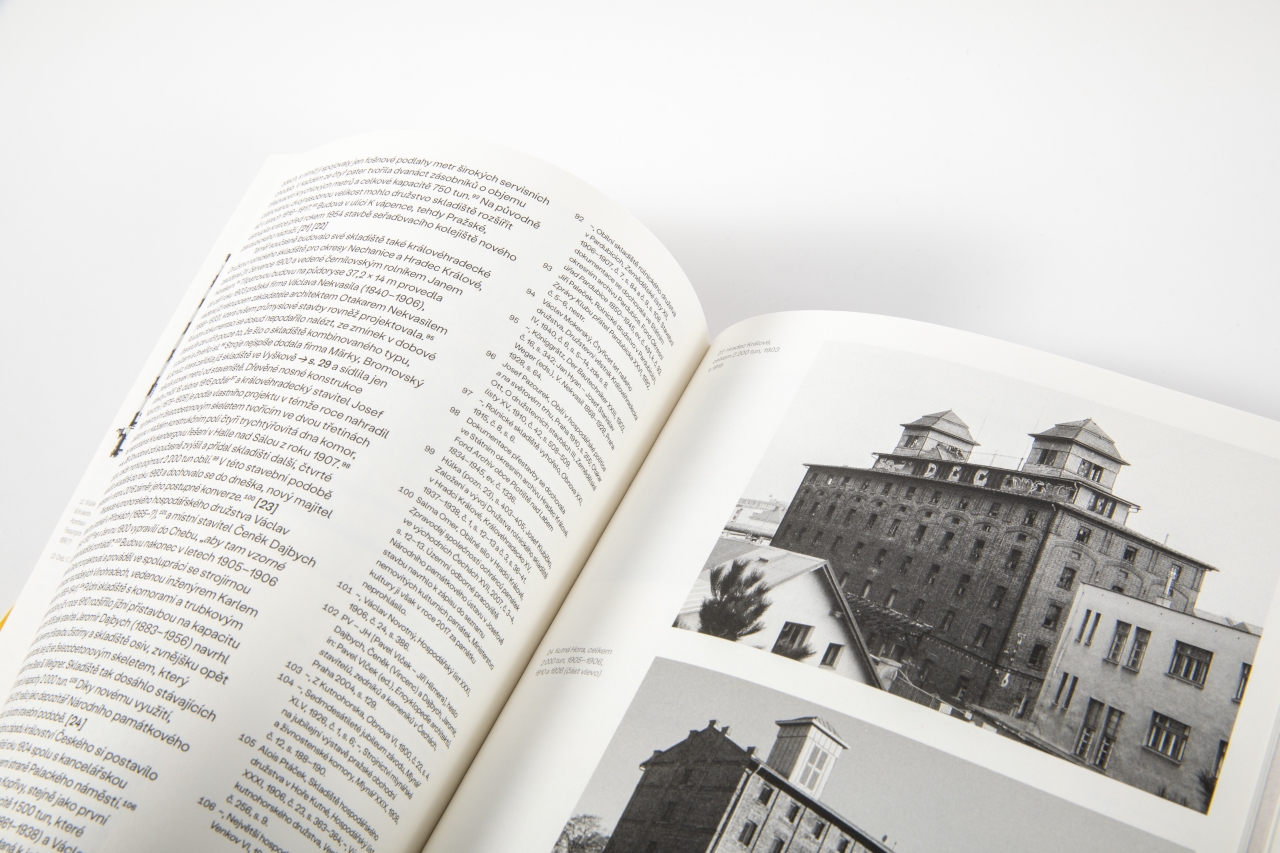

The first grain stores in the Czech lands were built by German cooperatives in Bílina and Litoměřice. Structurally they were much like traditional granaries, but they were additionally equipped with bucket elevators and conveyors. The standard design of mechanised granary was created in January 1899 for Der Centralverband der deutschen landwirtschaftlichen Genossenschaften Mährens und Schlesiens (the Union of German Cooperatives in Moravia and Silesia) by Ferdinand Hrach, a professor at the German Technical University in Brno. But this design was actually used only once, in Svitavy. A subsequent typological innovation came with the development of granaries with funnel-shaped floors, making it possible to empty the bins by gravity. From 1900 the ready-made designs for these stores and the machinery were supplied by the Nicolaus Heid company in Stockerau, Lower Austria. While this was an unnecessarily complicated and expensive type of building, the company was given preference as a domestic supplier, and consequently four Gossensystem grain stores were built in the Czech lands: in Česká Skalice, Žlutice, Most, and later Plzeň.

The standard design of grain store that was best suited to the needs and possibilities of the cooperatives, however, was ultimately developed and published by a specialised office that had no ties to any machinery manufacturer and was founded in Hannover in 1898 by mechanical engineer Friedrich Krukenberg and architect Ernst Wullekopf. Their two basic principles – the first being that it was built with a square layout to accommodate a rotary tube distributor and rather as a taller, narrower structure to accommodate the gravity flow tubes and spouts, and the second being that for storage it combined both granary floors and bins – were then further elaborated on throughout the first half of the 20th century. Standard grain stores, built according to the type design of the Wullekopf & Krukenberg Company can be found in Saxony, Thuringia, and what is today Polish Pomarania. The first one in the Czech lands was built in Cheb in 1899, followed in 1901 by others in Teplice, Ústí nad Labem, and Kouřim. In 1902 builder Karel Kašpar came up with an original variation on this design, and in cooperation with the milling engineering works of Josef Prokop and Sons designed a grain store (that unfortunately no longer exists) for a cooperative in Pardubice with Heid’s funnel-shaped floors, supported by a wooden frame that was structurally independent from the insulating perimeter walls – with this construction he was several decades ahead of his time.

During the First World War the technical and organisational foundations of the grain storage cooperatives served the nationalised grain-trading system and continued to evolve, as evidenced by a (never built) design for a façade that architect Jan Kotěra created for the cooperative grain store in Telč, or by the example of a granary building in Mirovice that was designed by architect Ladislav Ausobský and completed by the local cooperative before the grain market was denationalised again in June 1921.

1921–1945

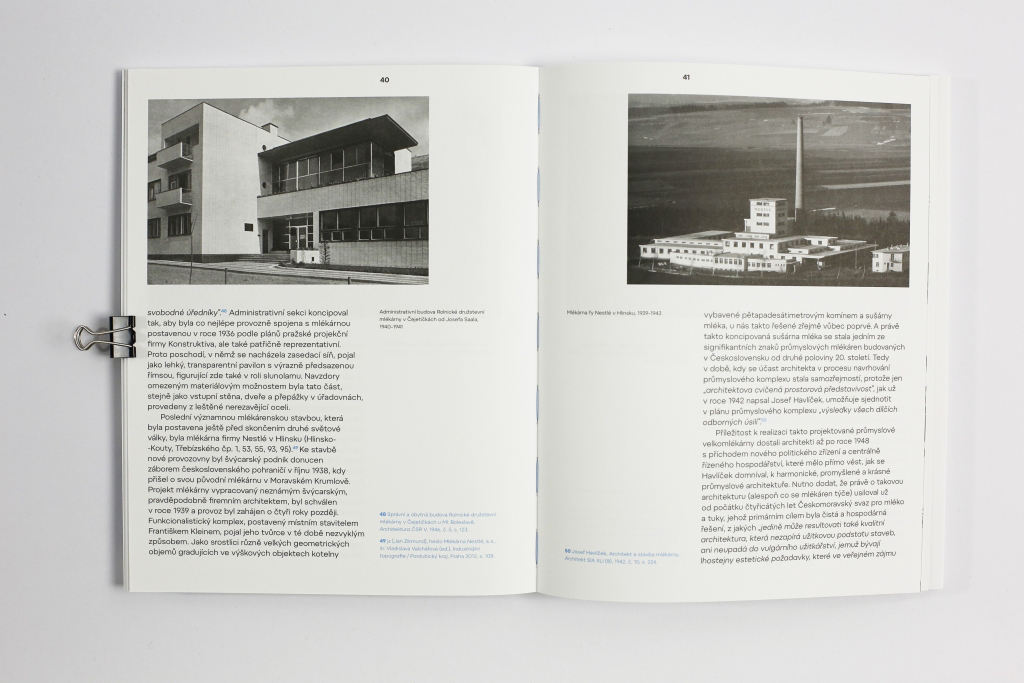

In the new Czechoslovak state, the centralisation of cooperatives as umbrella trade organisations continued and in the early 1920s they built several large reinforced-concrete grain stores that in design seemed more like stores used by private wholesalers. Structural engineer Emanuel Řehák designed buildings of this kind in 1920 for the largest such organisation, the Central Association of Economic Cooperatives (Ústřední jednota hospodářských družstev) in Prague, as did Otakar Vašíček, a construction engineer from the Provincial Construction Authority (Zemský stavební úřad), in 1925 for the Central Union of Czech Economic Societies (Ústřední svaz českých hospodářských společenstev) in Brno. The first large new structure of this type in Slovakia was introduced by the Farmers’ Granary Cooperative (Rolnícke skladištné družstvo) in Spišská Nová Ves in 1930 and was built and likely also designed by the company owned by engineers Hugo Kaboš and Eugen Fischer.

In the middle of the 1920s, the Board of Agriculture of the Bohemian Kingdom (Zemědělská rada pro království České), a professional institution that was established in 1873 for the purpose of supporting agriculture and to that time had been involved in assessing projects applying for state support, inserted an intervening hand in the evolution of granary buildings and began offering agricultural enterprises new granary designs that had been developed at the Institute of Agricultural Engineering of the University of Agriculture and Forest Engineering by architect Theodor Petřík and his colleagues, one of whom was Josef Hönich. Petřík’s granaries, built in Hořice and in Tišnov near Brno, used an affordable wooden frame and were regarded favourably for the contextual nature of their external architectural design. Similar in both aspects were the grain stores that architect Alfred Theimer designed for the Central Union of German Agricultural Cooperatives in Moravia (Zentralverband der deutschen landwirtschaftlichen Genossenschaften in Mähren) in the style of contemporary German Reformarchitektur. The largest of them, built in Jihlava and Uničov in 1927–1928, had plank floors inserted into a concrete frame and were topped with a lamella roof, which had only recently been invented then. Petřík’s rationalising but still architectonic endeavours in the field of architectural engineering were carried on by his student and assistant architect Karel Caivas, who in 1927–1931 worked for the Association of Agricultural Cooperatives (Jednota hospodářských družstev) in Prague. His grain stores – surviving examples of which can be found in Brandýs nad Labem, Beroun, Straškov, Milevsko, Rokycany, Dolní Roveň, Zlonice, and Pečky – document the gradual supplanting of wood first by steel and then reinforced-concrete support structures. For the rest of the interwar period the look of small granaries in the Czech lands was defined by a combination of Petřík’s picturesquely shaped roofs and the singular modernistic morphology of Caivas’s façades.

Reinforced-concrete silos which before the First World War had mainly been built for large mills only began to be used by the cooperatives once long-term grain storage was made possible with the invention of various methods of grain aeration. The first more widespread such structure in the Czech lands was developed in 1914 by the Rank Brothers company in Munich, where the walls of its cuboid bins were made of shaped bricks that had air ducts. A licence to use the design was obtained in the middle of the 1920s by Prague builder Václav Říha. He employed a Slovenian-born agricultural engineer named Fran Ciaffarin who had become acquainted with this design directly in Munich. The first Rank aerating silo in the Czech lands was built in 1926 for the model farm of the Czech Division of the Agricultural Board (Český odbor zemědělské rady) in Sobětice u Klatov. Its square bins could also be operated as part of a granary store – and the first structure like this in the Czech lands was built in Měšice in 1928.

A contemporary European advance in this storage technology came about with the construction of the (now no longer existing) cooperative granary in Znojmo, which was designed in 1927 and built by the Brno branch of the Austrian-German building company Wayss & Freytag and Meinong according to a new patent introduced by the Rank brothers in 1923, using bin walls with inclined lamellae, under which the repose slope of grain creates horizontal air ducts. That same year a small modification to this system, but one that represented a remarkable improvement, was introduced by the Munich-based company Schulz & Kling (SUKA), which then quickly came to dominate the market. The first silo in the Czech lands designed by this company was built in 1929 by miller Rudolf Wöhl, in the town of Raspenava, and a pair of connected, much larger silos were built a year later by a grain store cooperative in Žatec, and the same SUKA-silo was also used later by a cooperative in Uherské Hradiště.

The economic conditions that had led to the formation of grain storage cooperatives arose again a half century later, as during the Great Depression they once again became an instrument of state economic policy developed and advanced by the strongest political party in the Czechoslovak Republic, the Republican Party of Farmers and Peasants (Republikánská strana zemědělského a malorolnického lidu) – an agrarian party – and by Minister of Agriculture Milan Hodža, who was a member of this party. To support farmers in the hardest-hit areas of the country during the crisis, in 1933 he introduced a law that allowed cooperatives to run stores as public warehouses and to issue warrants. This legislation led to the construction of a network of grain stores in Slovakia that were built to the standard design created by architect Miloš Svitavský: this network of warehouses mostly consisted of six Rank-system silos, built in 1934–1936 in Topoľčany, Galanta, Veľký Meďer, Nové Město nad Váhom, Michalovce, and Trebišov, and a large combined grain store in Trnava. In Carpathian Ruthenia in 1936 the introduction of this legislation led to the construction of two large warehouses with steel grain silos, which were designed and built by Vítkovice steelworks in Baťovo and Berehovo, and also to the construction of three high-rise reinforced-concrete combined warehouses in Mukačevo, Užhorod, and Vinohradiv, which were designed by Rudolf Zelenka, an engineer at the Agricultural Construction Institute of the Agricultural Association of Czechoslovakia (Zemědělský stavební ústav při Zemědělské jednotě Československé republiky). He designed the same type of building also for the cooperative in Humpolec in Bohemia.

The construction of granaries in Czechoslovakia in the 1930s was fundamentally influenced by the country’s subsequent steps in the direction of a regulated economy in agriculture, like the one that had been devised on the international level primarily by the Czechoslovak Agricultural Academy’s Institute for Agriculture Policy (Ústav pro zemědělskou politiku Československé akademie zemědělské) headed by Edvard Reich. A government ordinance issued in July 1934, known as the ‘grain monopoly’ law, granted the exclusive right to trade grain at government-set prices to the newly established joint-stock Czechoslovak Grain Company (Československá obilní společnost). Thanks to the director of the largest domestic union, Ladislav Feierabend, it was the actors engaged in the grain trade who in proportional number became the company’s stockholders – consequently, as well as milling and trade organisations and consumer cooperatives, a 40% share was also held by grain storage cooperatives. The latter cooperatives were forced at the very least to double their storage capacity and introduce improvements that would enable them to provide long-term storage for the state’s strategic grain reserves.

In 1931 the Association of Agricultural Cooperatives established its own design office, which was headed by the then still little-known civil engineer Ladislav Platil, who while he was there successfully elaborated on the architectural and structural designs of Karel Caivas. The first grain store built according to Platil’s design was evidently built that same year in Mělník, the best preserved of his various cubiform structures can be found in Bechyně, Kasejovice, Kaznějov, Lično and Blatná, and the largest variant is in Sereď in the Považie region of Slovakia and dates from 1936. In many of them wooden rectangular bins with louvred aeration walls were built into their structural frames, a construction that was developed in the early 1930s by builder Antonín Kopta in collaboration with agronomist František Endler (‘the Endkop system’). It was first used in 1934 in a grain store in Blížejov, one that was probably designed by Karel Caivas, who at the time was promoting the use of these bins. About the same time, Platil’s office was also supplying the Association’s member cooperatives with projects for large stores that had plank floors supported by a reinforced-concrete frame and could also include Rank-system bins. The first such structure was built in Tábor, where this kind of frame made it possible to effectively take advantage of the irregular shape of the lot, and later again in Soběslav and Příbram, and among the largest examples were the structures in Louny and Mnichovo Hradiště. It was not until around the year 1937 that Platil’s office developed standard designs for smaller grain stores that differed only by the number of floors they had, as illustrated by the structures built in Jestřabí Lhota, Červené Pečky, Malešov, and Luže. New standard designs were developed again in the early 1940s.

The greatest degree of use of standard grain storage buildings was implemented by the Moravian Association of Agricultural Cooperatives in Brno, which worked with the Brno design office of architect Eduard Žáček. This is the office that can be considered to have come up with the design for a series of large granary-type stores that were built in 1935 in Velké Meziříčí, Prostějov, and Hranice and the following year in Uherský Brod, Kyjov, and Konice. But it was also and most notably the creator of a standard design for a reinforced-concrete-framed store with plank floors with a capacity for 700 tonnes of grain, which in 1936 was used, for example, by cooperatives in Dačice, Nesovice, Uničov, Telč, Bransouze, Náměšť na Hané, and Rosice. One atypical design is that, for example, of a ten-storey structure in Moravské Budějovice, where it was possible to obtain just a small plot of land, and another is that of a building in Holešov, which has a riveted steel frame.

The far less numerous granary cooperatives formed by Catholic farmers and tied to the Czechoslovak People’s Party (Československá strana lidová) began after the introduction of the monopoly to compete fiercely with the cooperatives with agrarian-party links, and soon in many localities it was possible to come across two granaries, often within sight of each other: a granary with Republican Party links and one aligned with the People’s Party. For the Moravian cooperatives (called Zádruha) the ‘People’s-Party’ granaries were built by the Prostějov-based company Gustav Bittner and Antonín Pavlovský: these were granary-type buildings with beam ceilings supported by steel columns and were built in 1936–1938 in Prostějov, Kojetín, Brodek u Prostějova, and Příbor. In Bohemia, the ‘People’s-Party’ cooperatives in 1937 used a standard grain store design with a reinforced concrete frame and plank floors that was created by engineer Fran Ciaffarin, examples of which have survived in Chotěboř, Čáslav, and Bechyně; in 2018 the only granary of this type equipped with Rank silos, brought by Ciaffarin to the Czech lands, which was located in Hradec Králové, was demolished.

The Central Union of German Agricultural Cooperatives (Ústřední svaz německých zemědělských družstev / Zentralverband der deutschen landwirtschaftlichen Genossenschaften) in Moravia and Silesia, as a shareholder in the Czechoslovak Grain Company (Československá obilní společnost), continued to work with architect Alfred Theimer, who designed a series of standard stores for the union that took the form of a brick building with a wooden interior frame and a high truss roof that housed the top granary floor. Two-storey versions of this grain store have survived in Potštát and Šlapanov in Vysočina, and there are two granaries that were built as three-storey versions of this project that are still standing and in their original state in the Znojmo region in the villages of Šumná and Božice, while the last structure in this series, and the one most fully preserved, is represented by a horizontal version of the granary that was constructed in 1939–1940 in Hanušovice. Alfred Theimer also apparently collaborated on SUKA-system silos for the Union that were structurally designed in 1935–1938 by his brother, and a building-company shareholder, Otto Friedrich Theimer, who then began working directly for the Munich-based office of Schulz & Kling and later became an internationally renowned expert on these structures. The first such silo was built by a German cooperative in Pohořelice and was demolished in 2010, but a silo designed at the same time and built slightly later in Moravská Třebová which was added to an older grain floor building by Alfred Theimer, has survived, as have the silos in Uničov and Opava. Wherever cooperatives did not yet have their own grain store and did not have a large enough piece of land to build on either, the Union had reinforced-concrete tower buildings built that had ventilated silos combined with grain floors – examples are the stores in Fulnek and Maršíkov.

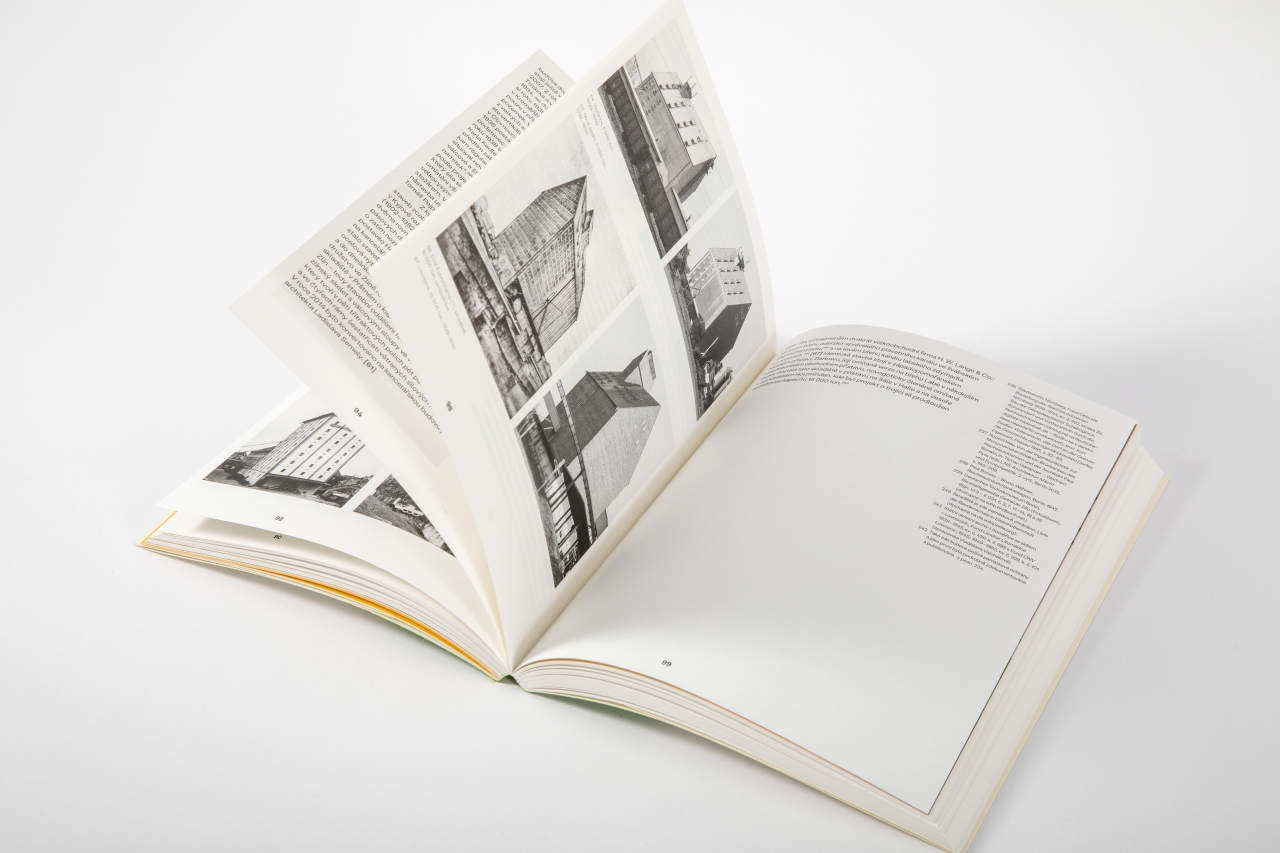

In 1939 the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia became part of the state-controlled economy of the German Reich, which sought to increase the efficiency of agricultural production in order to achieve food independence during the planned war. A part of this was the generous state support that began to be provided in 1938 for the construction of granaries, but only on the condition that one of the standard designs that had been drawn up by the Reichsamtfür Wirtschaftsausbau was used. The two largest types, which combined flat-slab grain floors supported by mushroom columns with a system of eight-, four-, and three-sided deep bins on an elongated floor plan, were called ‘Reichsspeicher’ . Two of three grain stores with a 5,000-tonne capacity built in 1939–1940 by the Oberste Bauleitung der Reichsautobahnen Nürnberg, to a design apparently created by architect Paul Bonatz, are located on what is today Czech territory: one in Vojtanov and one in Nové Sedlo near the train station Žabokliky, while the third such structure is in Schwandorf in Upper Palatinate. Around the same time, the wholesale company of H. W. Lange & Co. built the biggest type of Reichsspeicher for itself in Lovosice, with a 10,000-tonne capacity, which architect Emil Fahrenkamp worked on. However, it was evidently modified to conform to the construction traditions of its base city of Hamburg, thus featuring klinker-brick facades. The company built the same store also on the banks of the Oder-Spree Canal in Eisenhüttenstadt, Swabia.

1945–1989

Immediately in 1945 the Ministry of Food was established so that all agricultural sales and purchases in Czechoslovakia could be managed centrally, but both the large purchasing federations and syndicates and the small granary cooperatives nonetheless remained in the country unchanged until 1948. Not many new grain stores were built up to the end of the 1940s, but the most architecturally interesting ones were designed by Jan Tymich for the town of Jevíčko and Bohuslav Fuchs for Židlochovice.

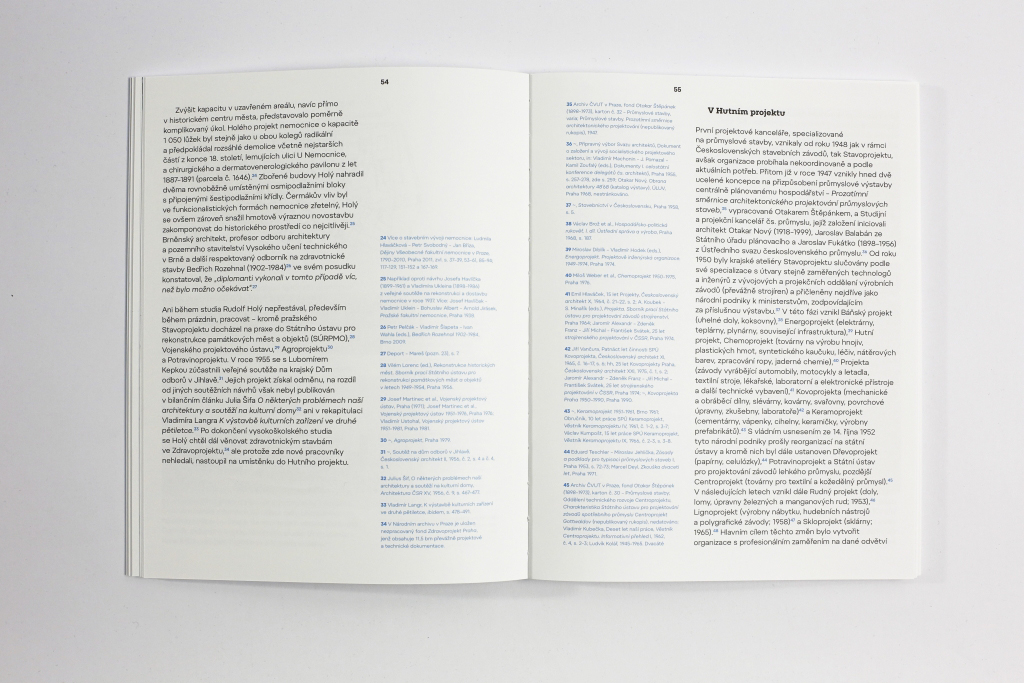

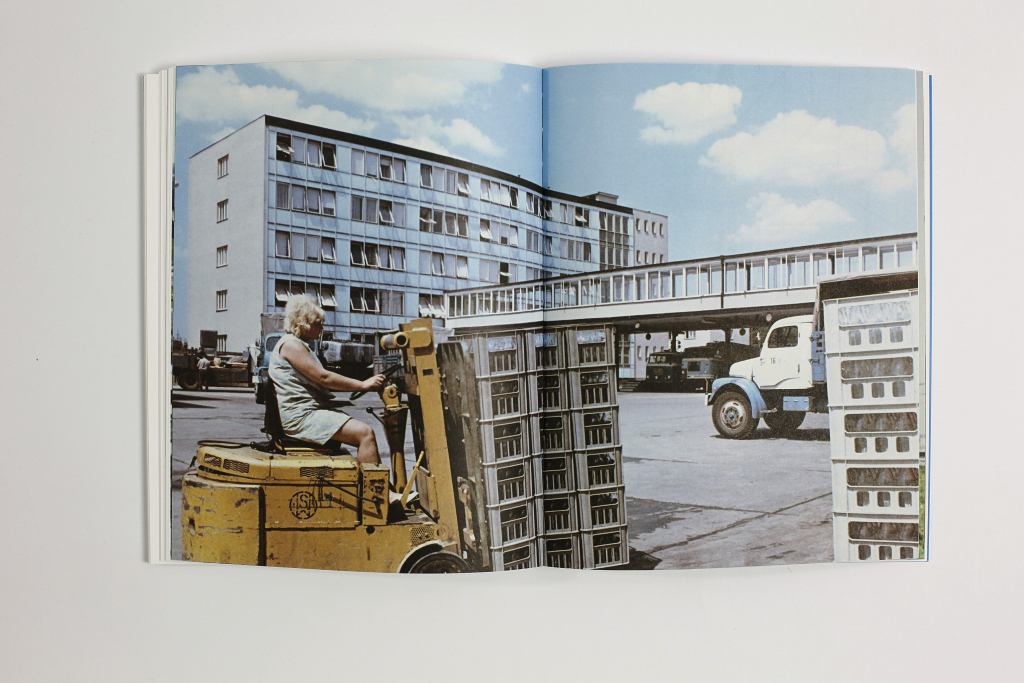

After the communist coup in February 1948, the entire agricultural sector was nationalised – from the cooperatives to large-scale farms and even the property of small farmers. The state ran the entire system of agricultural purchasing by setting up coordination platforms such as the Central Office for the Management of Agricultural Products (Ústředí pro hospodaření zemědělskými výrobky, 1948–1951), the Central Purchasing Administration (Hlavní správa výkupu, 1951–1958), the Association of Purchasing Enterprises (Sdružení výkupních podniků, 1958–1962), the Central Administration for the Purchase of Agricultural Products (Ústřední správa nákupu zemědělských výrobků, 1962–1967), and Agricultural Supply and Purchasing (Zemědělské zásobování a nákup, 1962–1989). At the same time, the entire building industry and the process of architectural work were transformed into nationalised formats and special design offices dedicated to the construction of granary structures were set up: the design office of the Central Council of Cooperatives (Projekční kancelář Ústřední rady družstev, later Potravinoprojekt), The design department of the Association of Purchasing Enterprises (Projekční oddělení Sdružení výkupních podniků), the Design Office of the Central Administration for the Purchase of Agricultural Products (Projekce Ústřední správy nákupu zemědělských výrobků) and construction enterprises (Průmstav Pardubice, Stavoindustria Bratislava, and others).

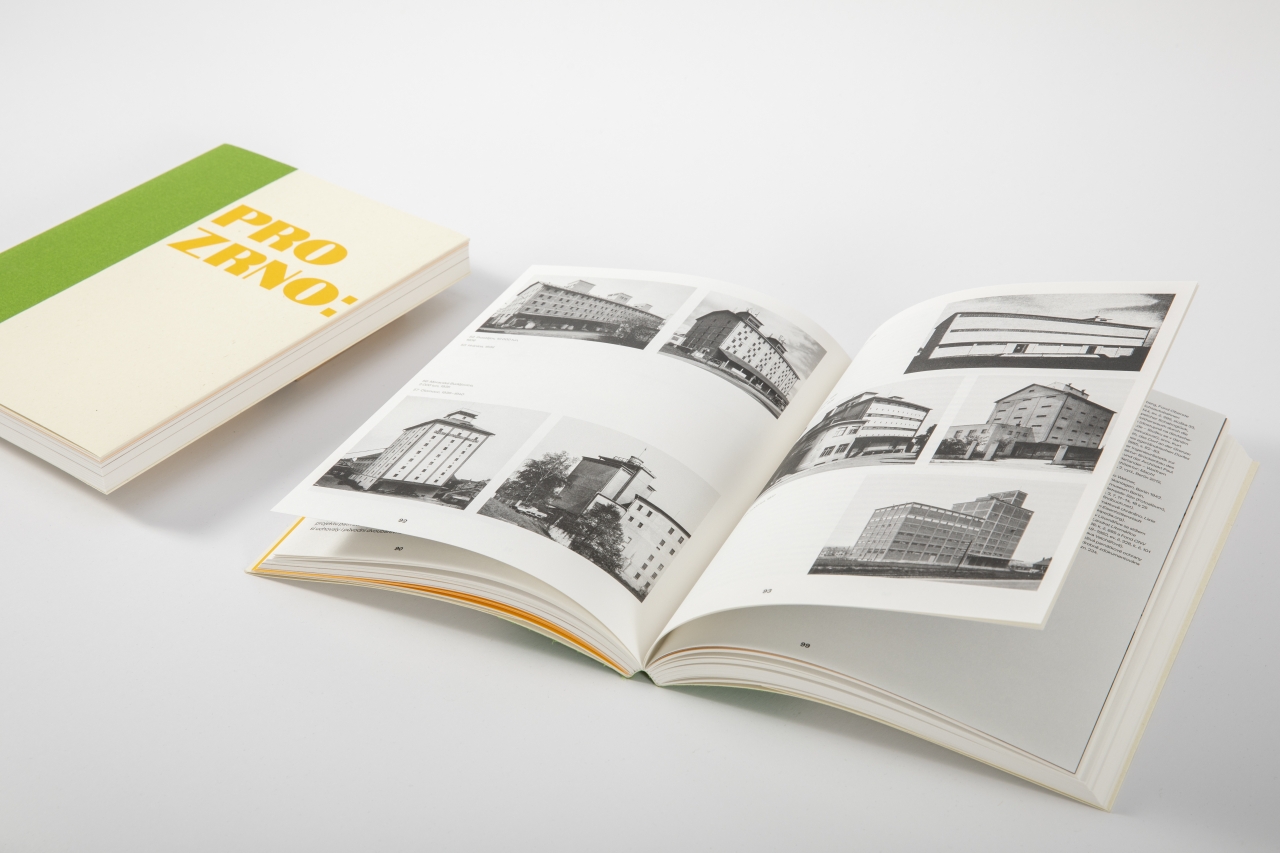

The first post-war large-volume grain stores, combining a floor granary with deep bins, was designed in 1948–1953 by the design office of the Central Council of Cooperatives. The structures built in České Budějovice, Hrochův Týnec, Pardubice, Přerov, Batelov, Kojetice, and Rakšice can be regarded as an important first step towards a new generation of standardised grain store.

In 1953 the design office of the Central Council of Cooperatives became the base for a new state design institution dedicated to food-industry structures called Potravinoprojekt. Departments were set up in this office that were devoted solely to working on grain stores: Centre 12 in Prague, headed by architect Vojtěch Florian, and Centre 21 in Pardubice, where the central figures were architects Jaroslav Dědič and František Cabicar and engineer Alfréd Geřábek.

Grain stores in the centrally run economy were thereafter supposed to be built solely to standard designs. The most widespread design in the 1950s was a combined grain store with a 3,600-tonne capacity, which was created in 1952 by Jaroslav Dědič and František Cabicar. By the year 1959 it had been used in seventeen locations in Czechoslovakia. Jaroslav Dědič and František Cabicar were also the creators of a standard design of grain store with a capacity to hold 6,000 tonnes of grain, again to be stored both on grain floors and in deep bins. This had been used just seven times, the best-preserved example, which includes the original technology, is located in Ronov nad Doubravou, while a longer version was built in Senica, Slovakia. In the meantime, Vojtěch Florian’s team prepared two types of silos with a capacity for 15,600 tonnes, which was ultimately never built, and 10,500 tonnes, which can only be found in Vrbno nad Lesy.

During the 1950s a series of standard designs were developed that tested various operational concepts and structural solutions. In 1957 Alfréd Geřábek designed a modular reinforced-concrete silo that could easily be connected to older granaries. The prototype was built three years later in Poběžovice. Cost considerations were also behind a design for a ‘gravity silo’ in 1958 at Potravinoprojekt in Pardubice by architects Josef Doležal and Jan Cupal. A characteristic feature of this type was that circular bins were used in it for the first time and visibly reflected in the shape of the structure. Silos with a 4,650-tonne capacity were built in Jičín, Kouřim, Hodonice, and Stod, and a larger version was then built in Česká Skalice, Kostelec nad Orlicí, and Toužim. The long-term storage of grain in standard single-storey hangars was explored as well. The first designs were developed in the design office of the Central Council of Cooperatives, but the versions that were ultimately constructed were assembled two-tract halls of prefabricated reinforced-concrete components that could also be grouped in fours to form ‘bases’. Examples of these can be found in Křinec, Protivín, and Šamorín in Slovakia.

In the 1950s a series of remarkable grain stores were built in Slovakia, some of which were even successfully replicated. The largest one, with a capacity of 12,000 tonnes, was designed in 1954 at Potravinoprojekt in Prague by Ladislav Kučera, Jaroslav Musil, Miloš Kožíšek, and Bohuslav Dvořák and was built in Michalovce, Pohronský Ruskov, and, with a modified architectural design, in Vráble. Interesting grain stores can also be found in Námestovo and Parchovany (3,000 tonnes), Zlatovce, Lipany, and Čečejovce (4,550 tonnes), while small standard granaries with a capacity for 25, 50, or 100 wagons of grain were also well-suited to the agricultural character of the Slovak landscape.

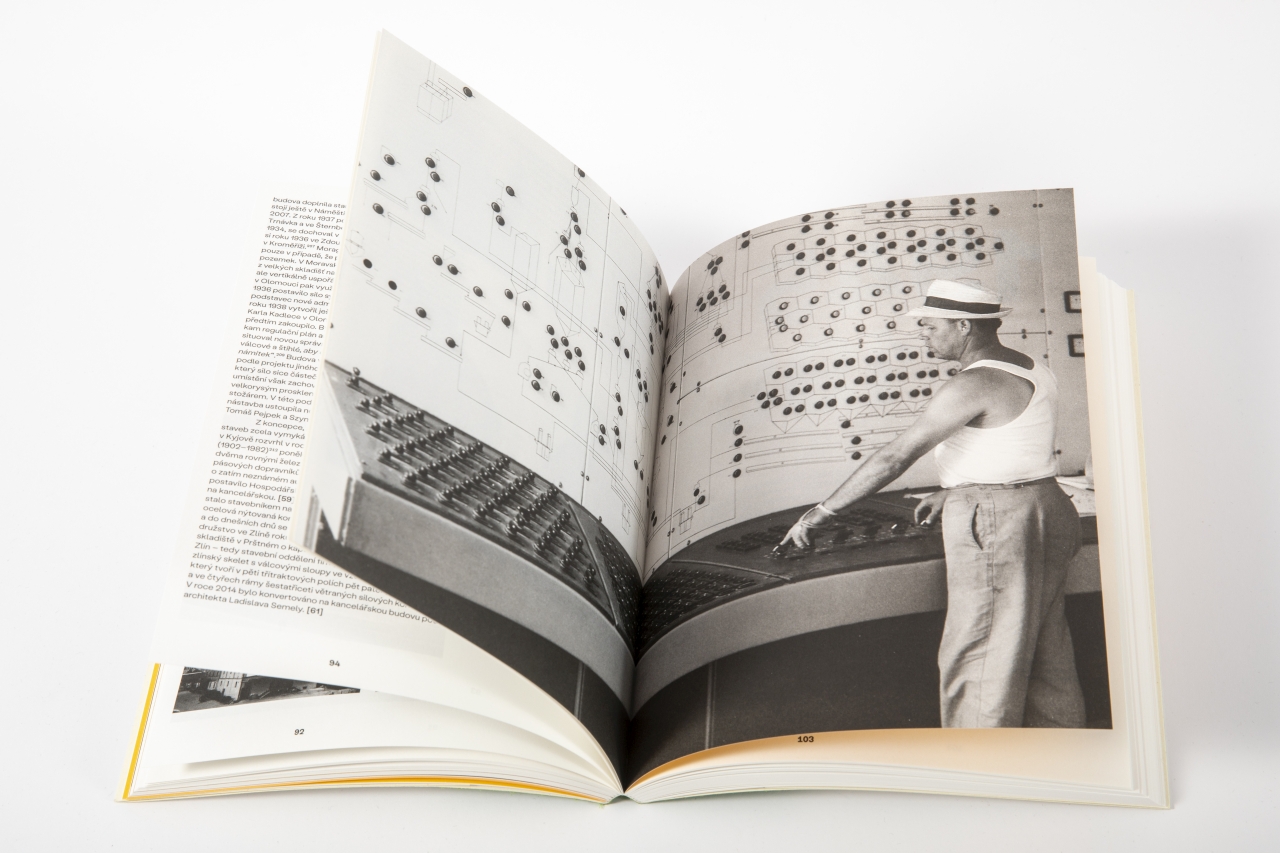

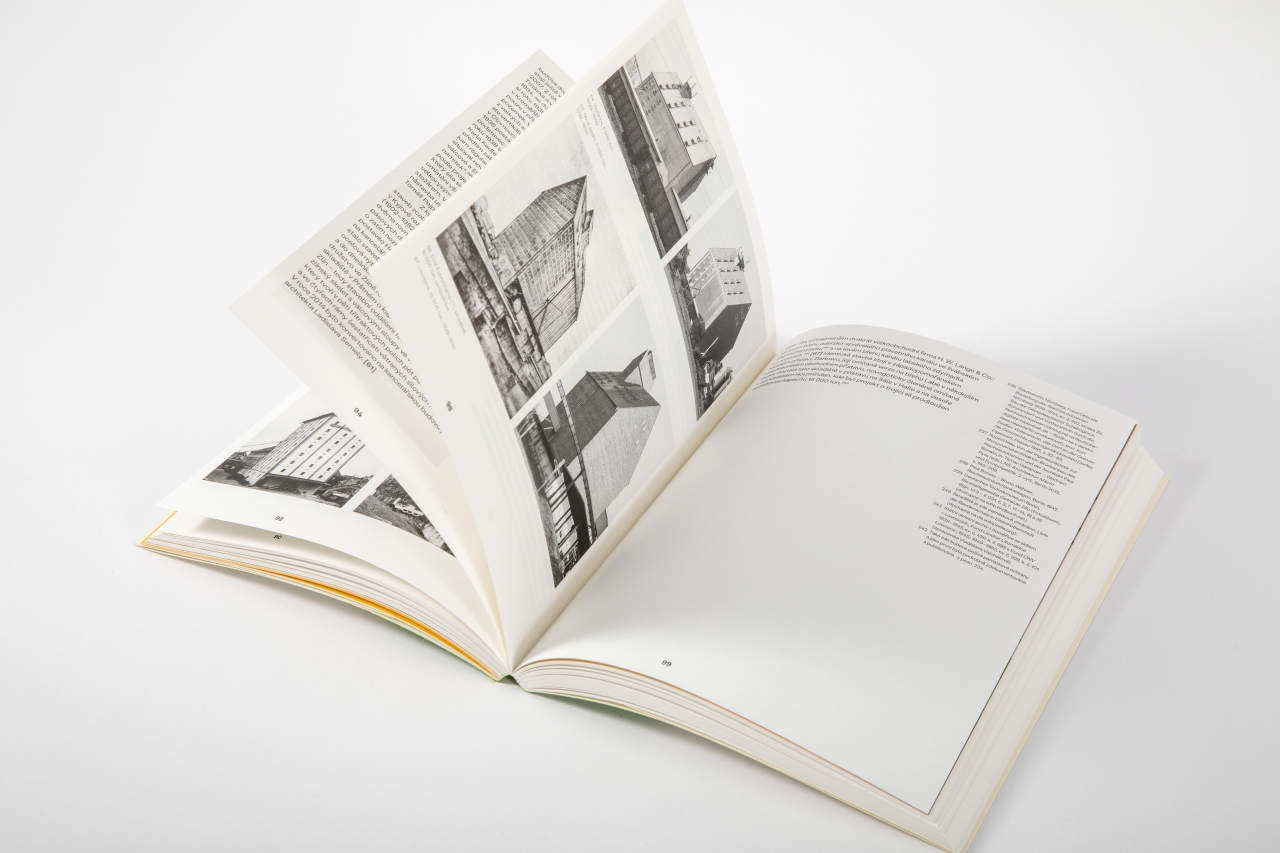

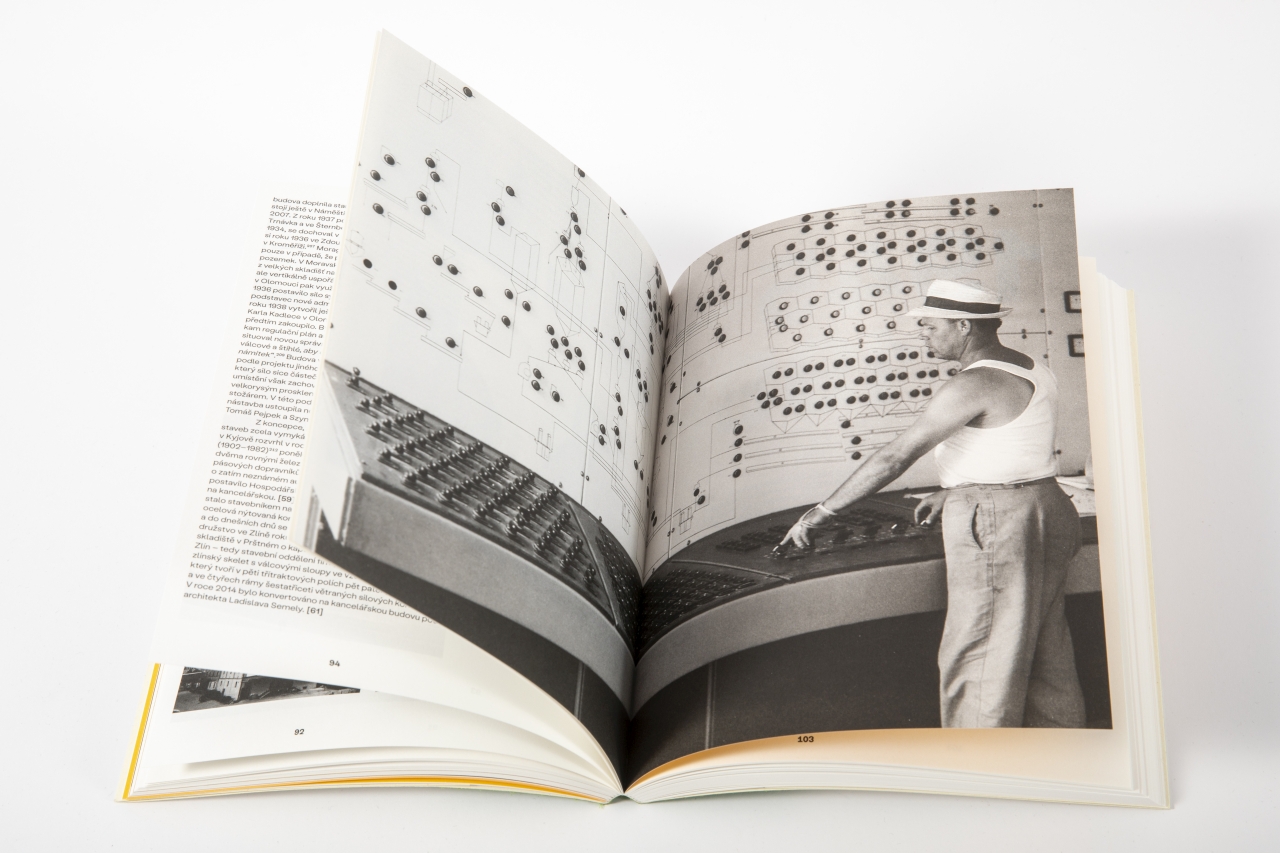

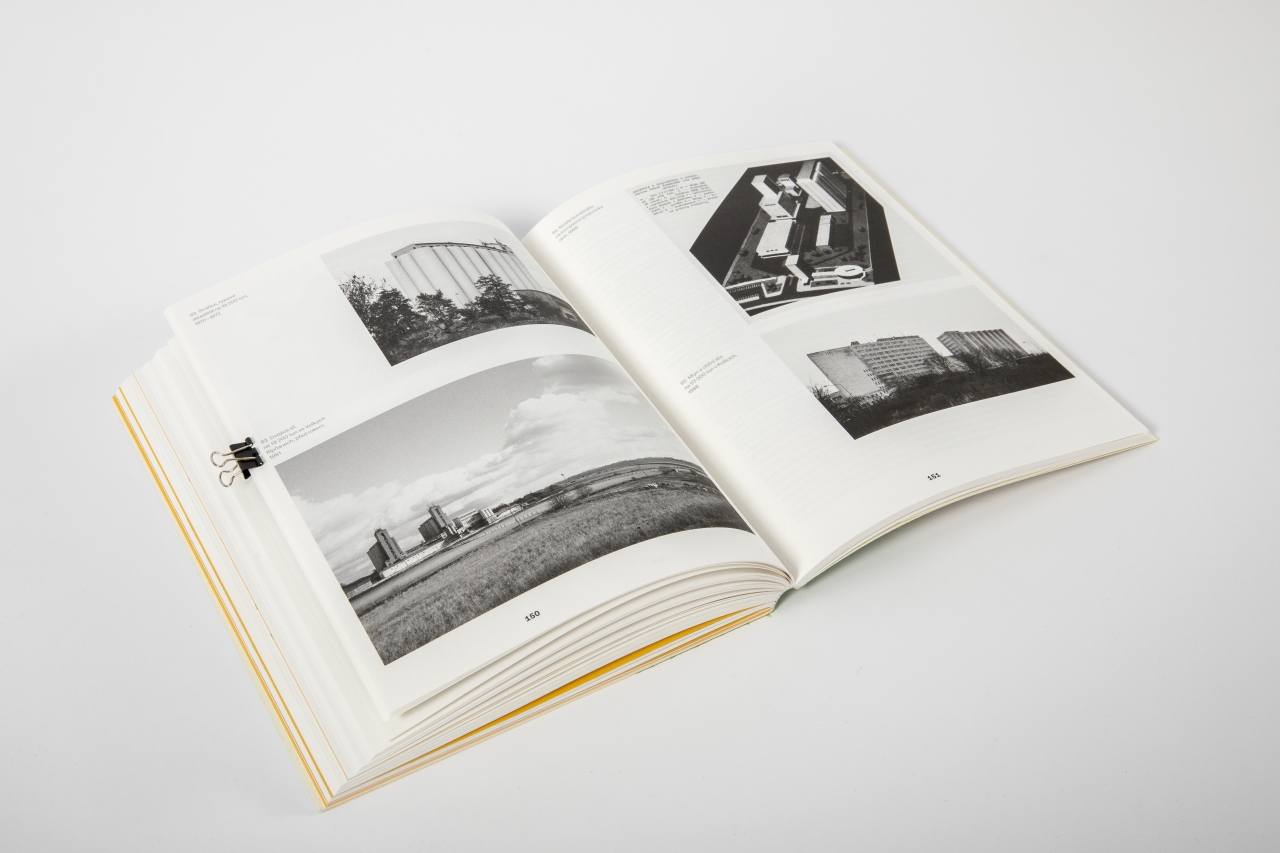

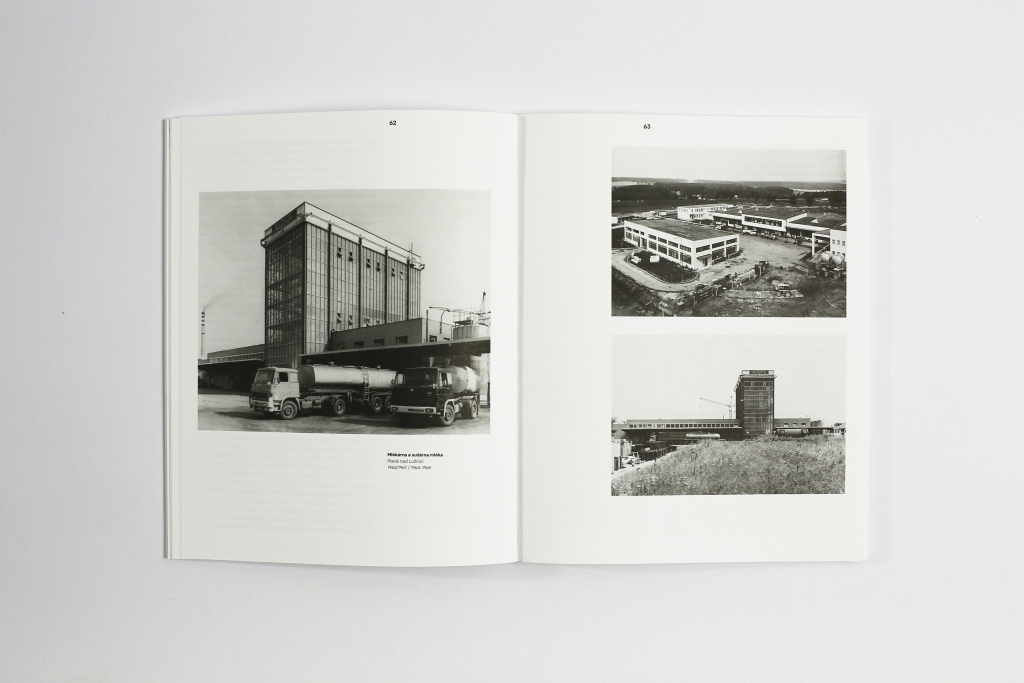

Despite all the efforts, it proved impossible to build the necessary capacity of modern storage on a scale and at a speed envisioned by the central planners. Construction was hampered most by the slow pace of construction work, which usually took several years, and by the constant legislative changes throughout the entire apparatus of construction and design, changes that regulated what positions investors, designers, and suppliers occupied in relation to each other. All these maladies were supposed to be resolved by a fundamental reworking of the overall concept of storage and building design. This ultimately came in the form of a silo with a 21,000-tonne capacity, which became the most widely used type and was built at more than 89 locations in Czechoslovakia. The design was developed in 1958 under the direction of Vojtěch Florian in the design group of the Association of Purchasing Enterprises’ technical department by Ladislav Procházka, Ladislav Kučera, and structural analyst Josef Vostřel, while the architectural design was created by Bohuslav Dvořák. The structure is a reinforced-concrete monolith comprising 25 interconnected hexagonal bins, and its operations are completely automated and controlled remotely from a control room. The first silo of this type was completed in Pardubice in 1961. In the years that followed a number of modifications were made, both structurally and in terms of its capacity, leading to silos with a capacity of 3,600 tonnes in Vlašim and Šenov near Nový Jičín, 12,000 tonnes (in Martin), 22,700 tonnes (Trutnov), and most notably 23,000 tonnes, which was built in more than twenty locations in Czechoslovakia. In the 1960s two types of circular silos emerged: one with a 17,000-tonne capacity (1959, Pavel Fabián, Potravinoprojekt Bratislava), examples of which were only built in Slovakia, and one with a capacity of 19,200 tonnes of grain (1962, a design by the Central Administration for Purchasing Agricultural Products).

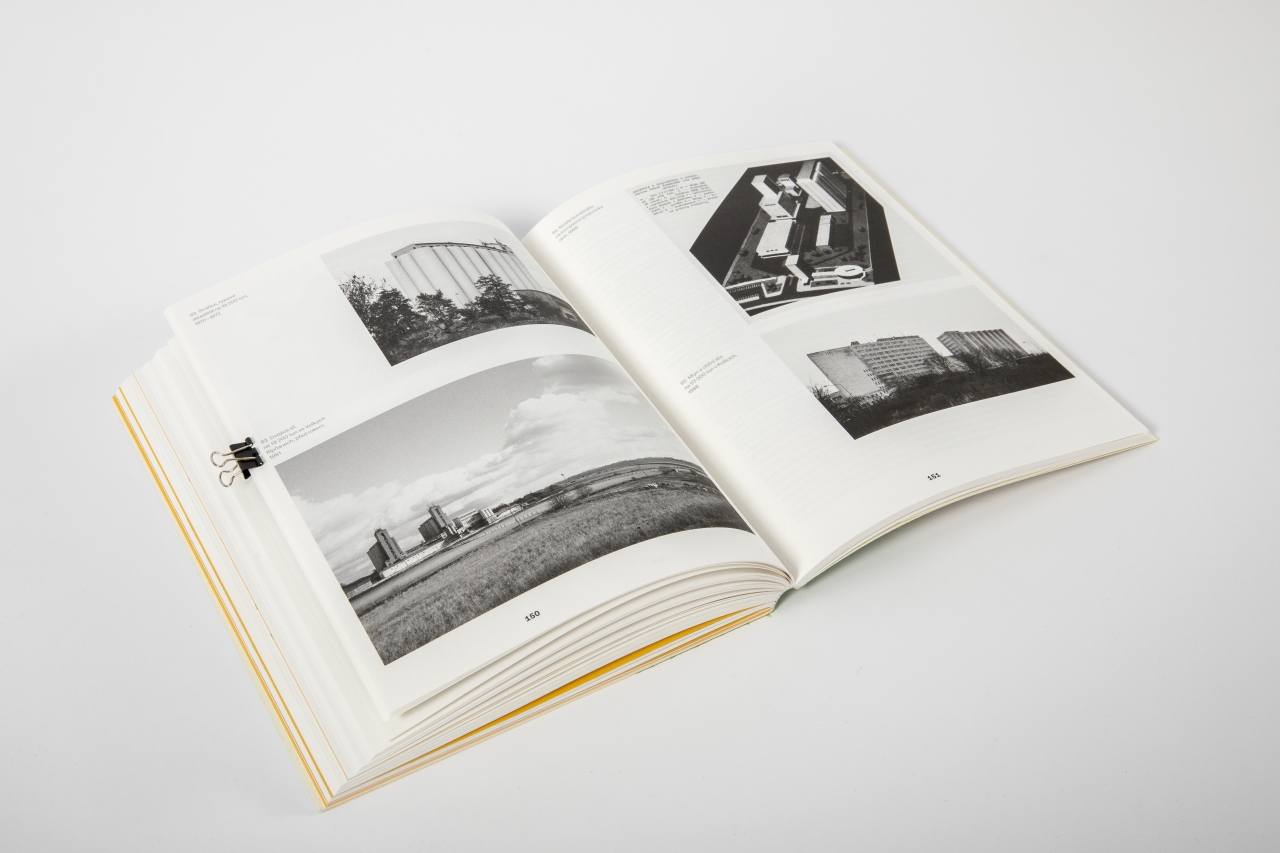

Starting in the 1970s steel began to replace reinforced concrete in silo construction. Alongside the ‘Štolfa’, a widespread type of small grain store, three standard designs of silos helped most to make up for the shortfall in capacity and they originated in the design department of Milling Machine Factories (Továrny mlýnských strojů / TMS), a national enterprise in Pardubice. The first silo, with a 20,000-tonne capacity, was built in Libáň, and there was an enlarged version with a capacity for 50,000 tonnes. A small modifiable silo known as the ZOOS that emerged out of the design department at TMS also became common in the late 1970s.

Events to compare architecture and construction methods were organised on the basis of agreements within the framework of COMECON (Rada vzájemné hospodářské pomoci / RVHP) or on the basis of politically favoured cooperation between state-socialist countries. An example of this cooperation was a silo with a capacity of 50,000 tonnes in Kněžmost, where the design and all the construction work was done by Budimex, an enterprise in Warsaw. Another Polish design office, Cukroprojekt Warszawa, designed a silo with a capacity for 66,000 tonnes of grain built in Milín. Two circular silos with a capacity of 38,000 tonnes built in Mimoň and Polepy were designed by Industrieprojektierung, an enterprise in Dessau.

Events abroad in the field of construction also influenced the nature of the final era of Czech grain store design. From the start of the 1970s the design department at the ZZN focused on ‘mammoth’ silos, which were supposed to make up for the persistent shortfall in storage capacity. In 1977–1982 a silo with a capacity of 92,000 tonnes was built in Šakvice, which was the largest one ever built in Czechoslovakia. Smaller versions with a 69,000-tonne capacity are standing in Zdislavice and Blovice, and the smallest ones are in Olomouc and Ivančice. The silo in Blovice was completed in 1990 and it was thus the last classic reinforced-concrete silo built on the territory of Czechoslovakia.

Summary translated by Robin Cassling

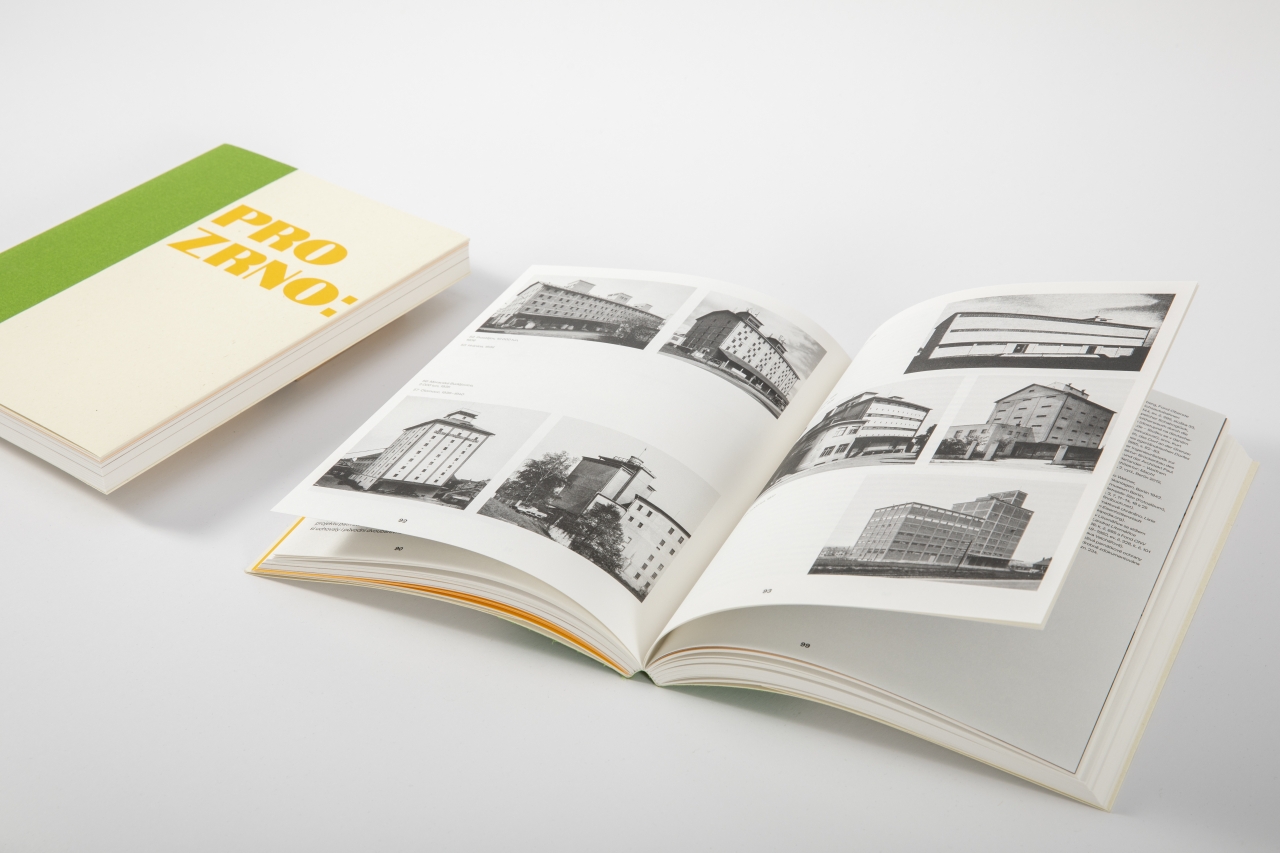

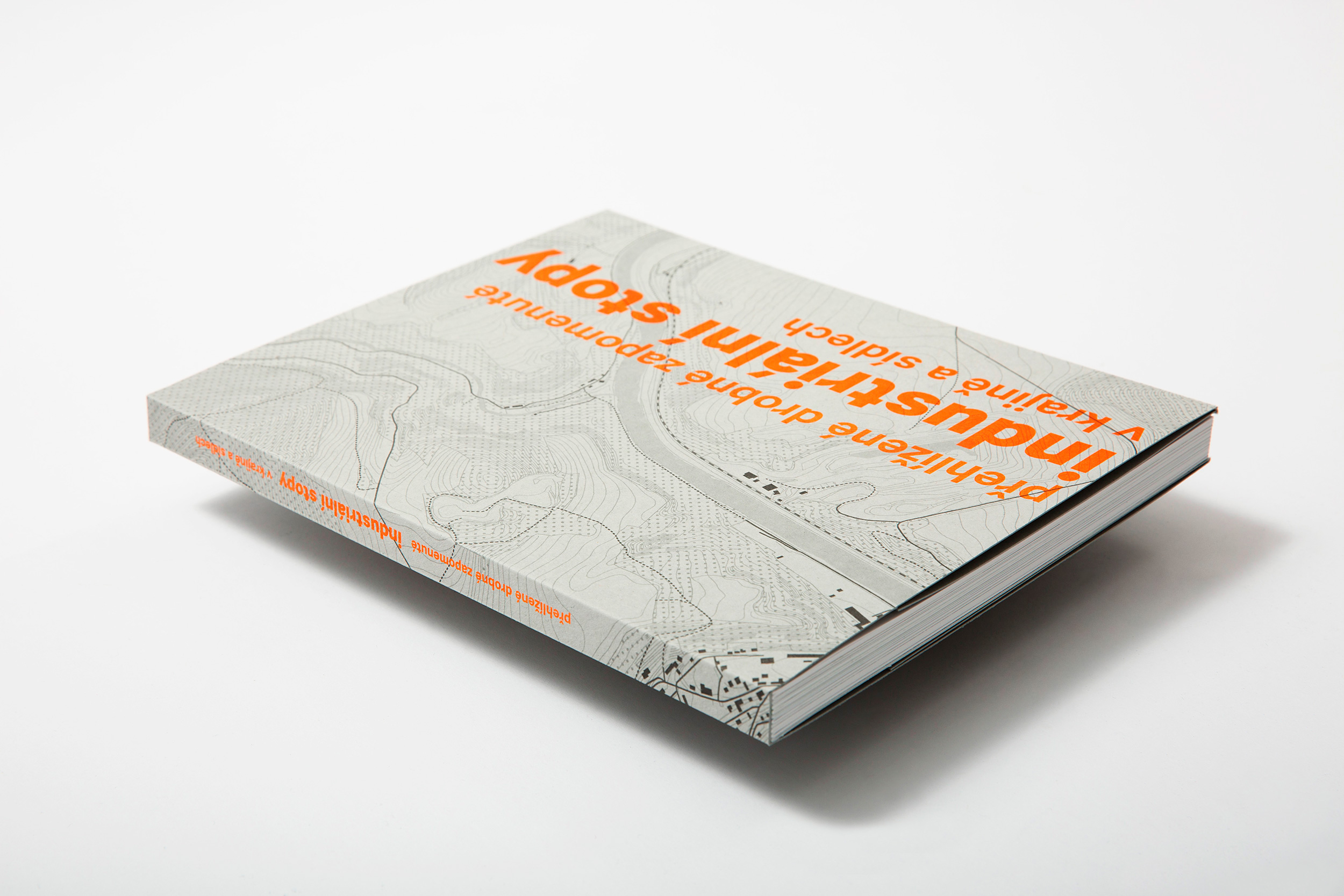

Lukáš Beran – Jan Zikmund, PRO ZRNO: Grain Stores and Silos 1898–1989, Prague 2018.

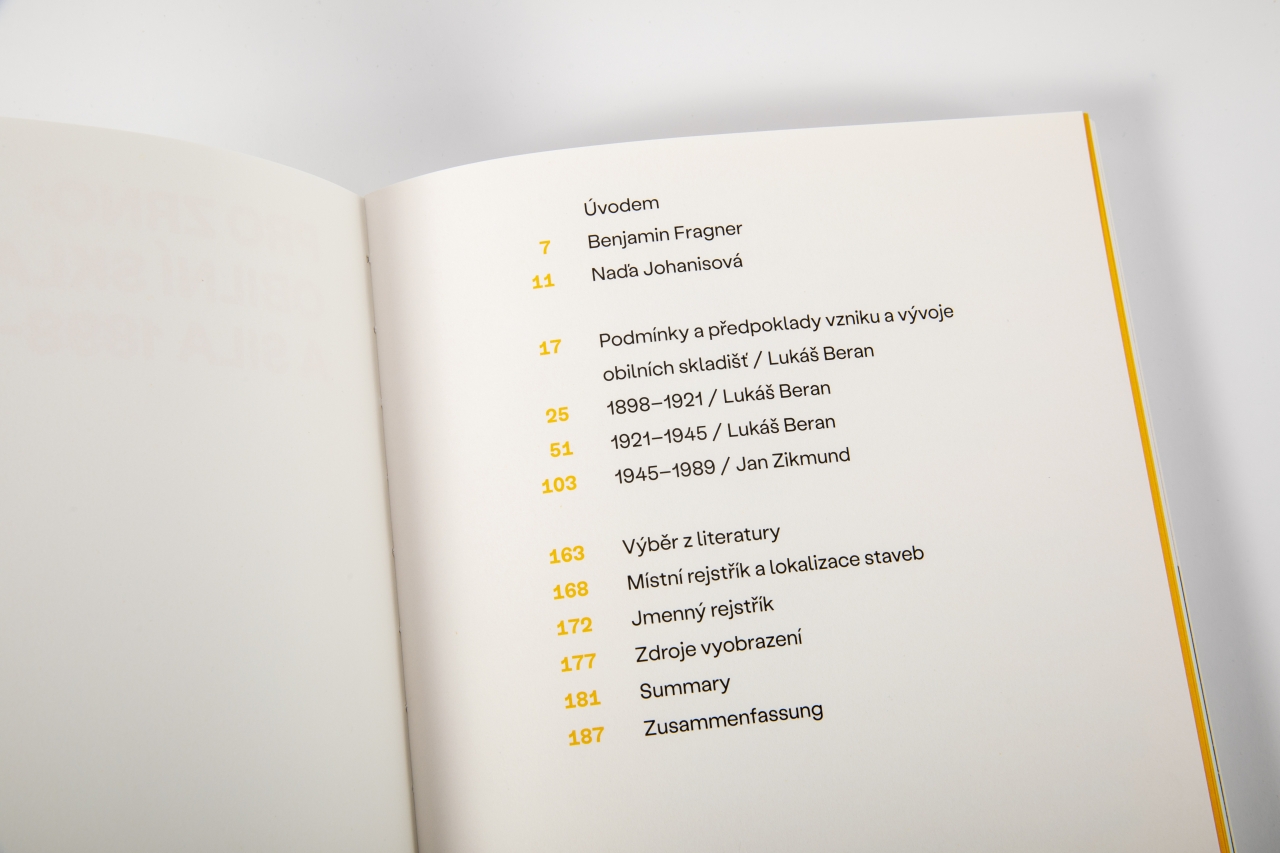

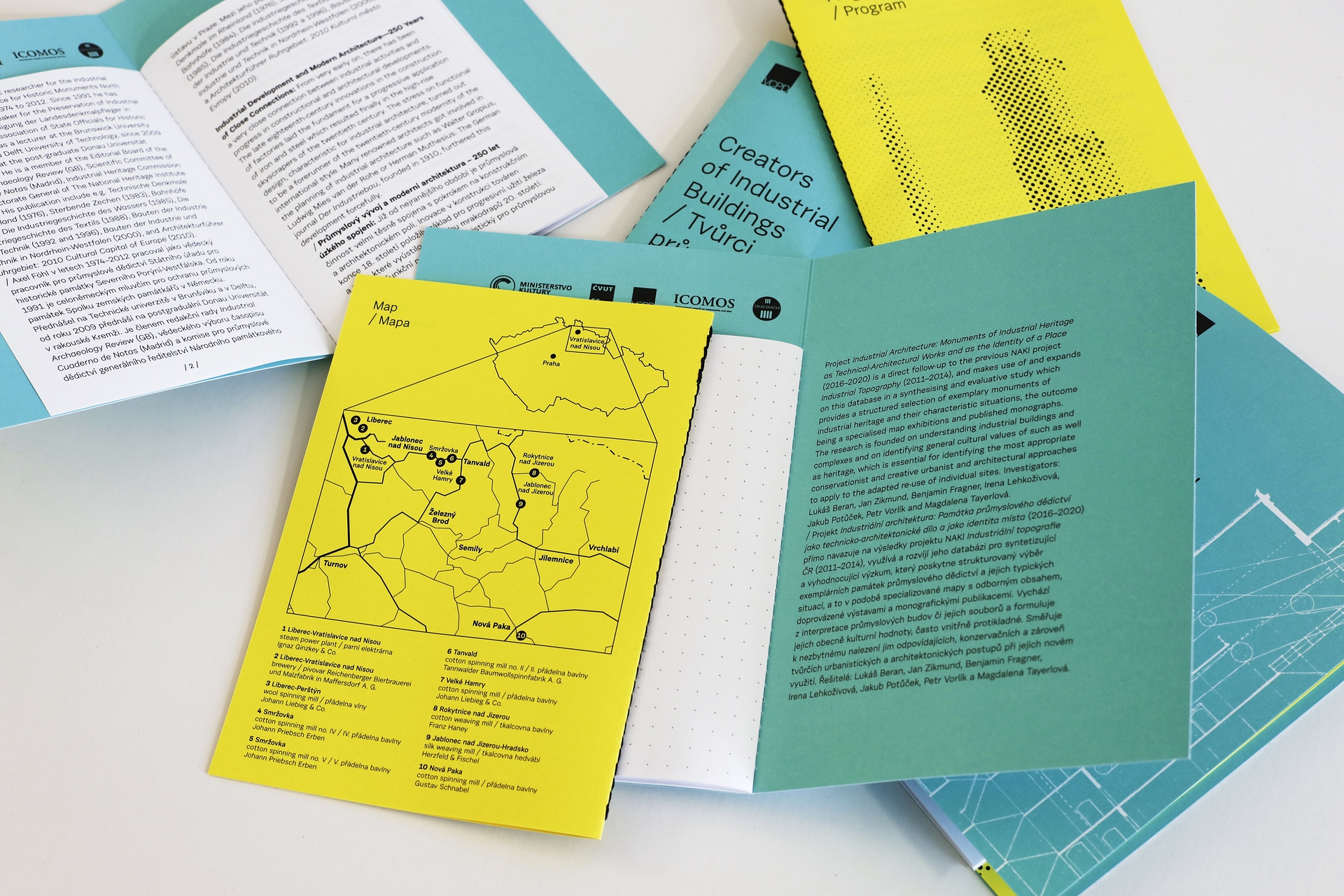

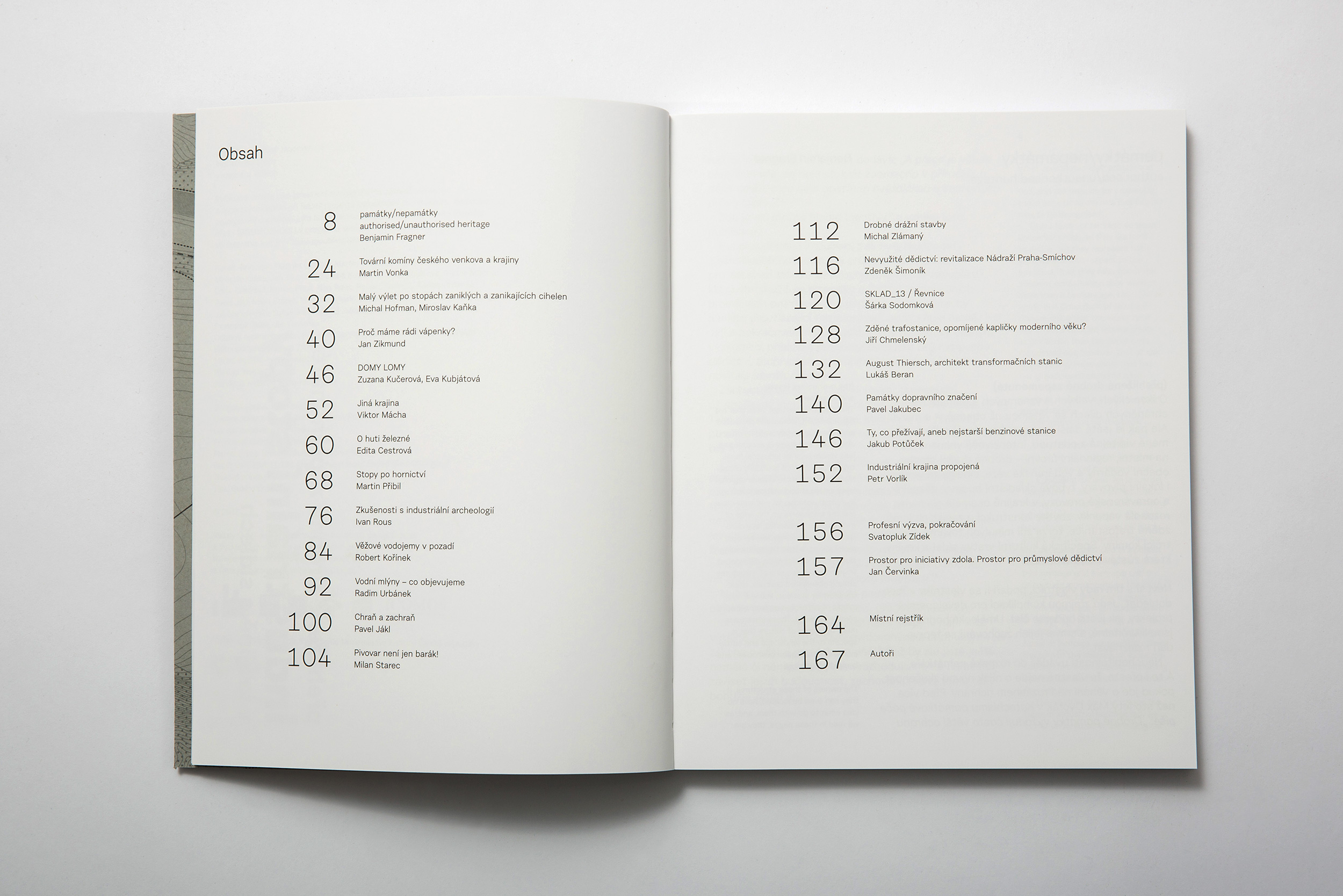

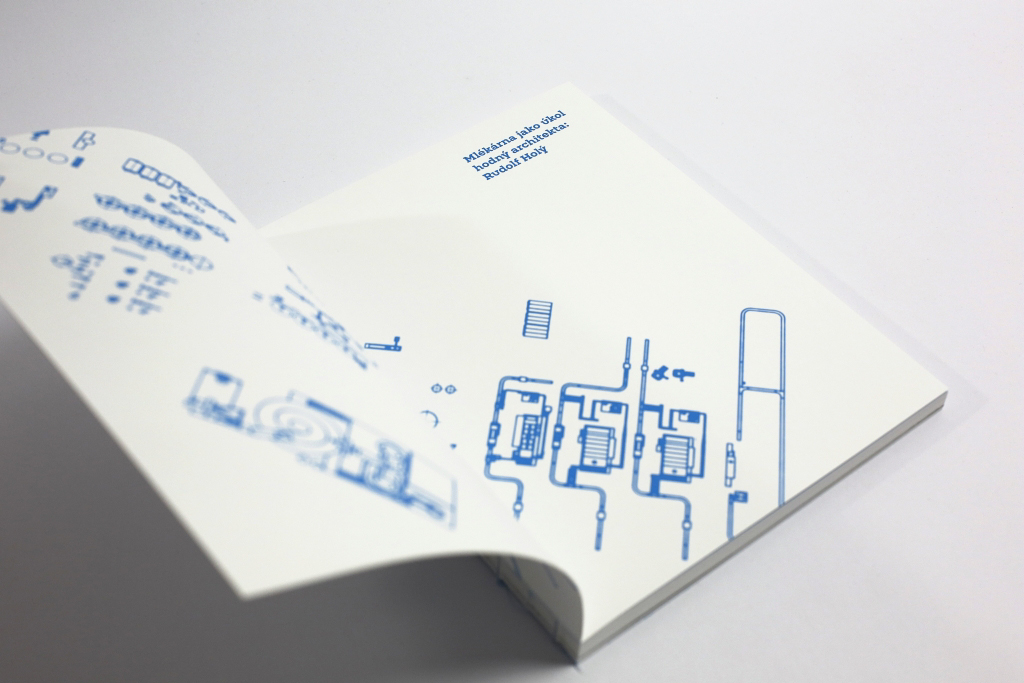

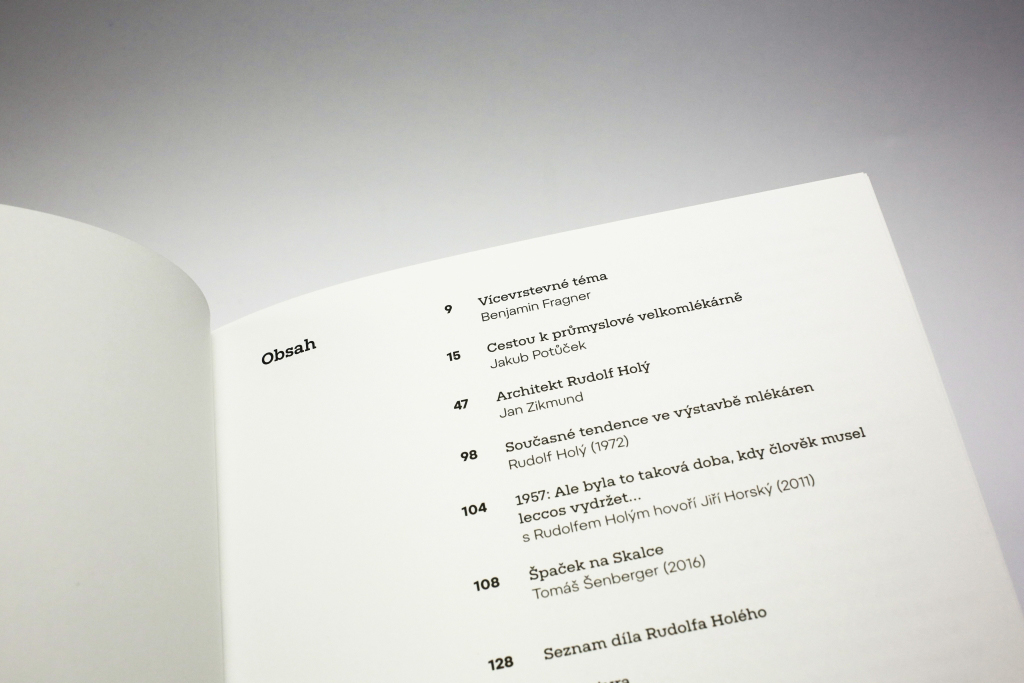

192 pages; Czech/summary in English and German; 176 images and plans; ISBN 978-80-01-06026-3 / authors Lukáš Beran, Jan Zikmund / co-authors Benjamin Fragner, Naďa Johanisová, Tereza Bartošíková, Jakub Potůček, Magdalena Tayerlová, Lukáš Tofan / scientific review Rostislav Švácha / proofreading Irena Hlinková / translation Robin Cassling, Tomáš Mařík / index of places Irena Lehkoživová / graphic design Jan Forejt (Formall) / treatment of reproductions Jiří Klíma (Formall) / production Gabriel Fragner (Formall) / fonts Notable and Stabil Grotesk / papers Arcoprint Milk White and Woodstock Betulla / print Helbich Printers / published by the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage FA CTU Prague 2018