Designing Dairies – A Job Worthy of an Architect: Rudolf Holý

After the Second World War industrial architecture underwent a radical transformation in just several years. Industry was nationalised, a new system for commissioning architectural projects was introduced, and the building industry was amalgamated with planning activities, but these were not the only new difficulties that architects had to contend with. It was the rigid system of economic planning and its close intertwining with the political regime that complicated the preparation of building projects and investment plans and often even got in the way of actual construction work. A priority of postwar Czechoslovakia was the conversion of industry into the foundation of the new economy that was outlined in the Two-Year Economic Plan (1947–1948) and then fully unfurled in the first Five-Year Plan (1949–1953). The amalgamated body of planning departments was not prepared for the envisioned level of industrial development, which was on a scale that is hard to image today. Special courses had to be introduced immediately at the schools of architecture, and separate planning departments dedicated to industrial structures had to be set up to provide professional support to tackle the complex planning operations in individual sectors of industry. A major role in this was played by a platform of theoretical work put forth by Otakar Štěpánek, Emil Hlaváček, Jiří Girsa, Emil Kovařík, Eduard Teschler, Miloš Vaněček, Jiří Vančura and Emanuel Podráský. Thanks to these experts, within a short period of time architects had a range of books and studies available to them that defined the requirements and parameters of the modern factory.

Years of organisational changes and an atmosphere of constant change in search of the best methods for industrial architecture and revisions of things from the past not only left their mark on the practical work but also on the architecture itself, which for a long time kept the strong interwar tradition of functionalism alive, thanks primarily to the work of such figures as František Albert Libra, Oskar Oehler/Olár, and the distinctive Zlín school, headed up by Jiří Voženílek, Vladimír Kubečka, Zdeněk Plesník, and Miroslav Drofa. However, these attempts at individual approaches to industrial architecture could not survive long. More distinctive forms of artistic expression in industrial architecture were quashed for a time not so much by the advance of Soviet-style Socialist Realism, which made almost no mark in industrial architecture, but by the emphasis placed on economising. Standardisation became the central point of theoretical discussions on industrial structures. The introduction of standardisation into building practice did not proceed in the way theorists had imagined. The theoretical discussions nevertheless made it possible to define, in step with international developments, the basic parameters of the modern industrial plant (universality, the use of zones and sections, monoblocks, windowless buildings, and open industrial structures) even in the rigid conditions of civil engineering in Czechoslovakia.

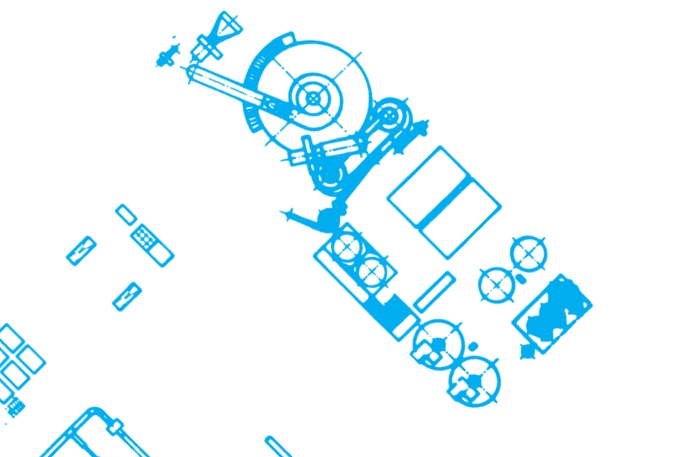

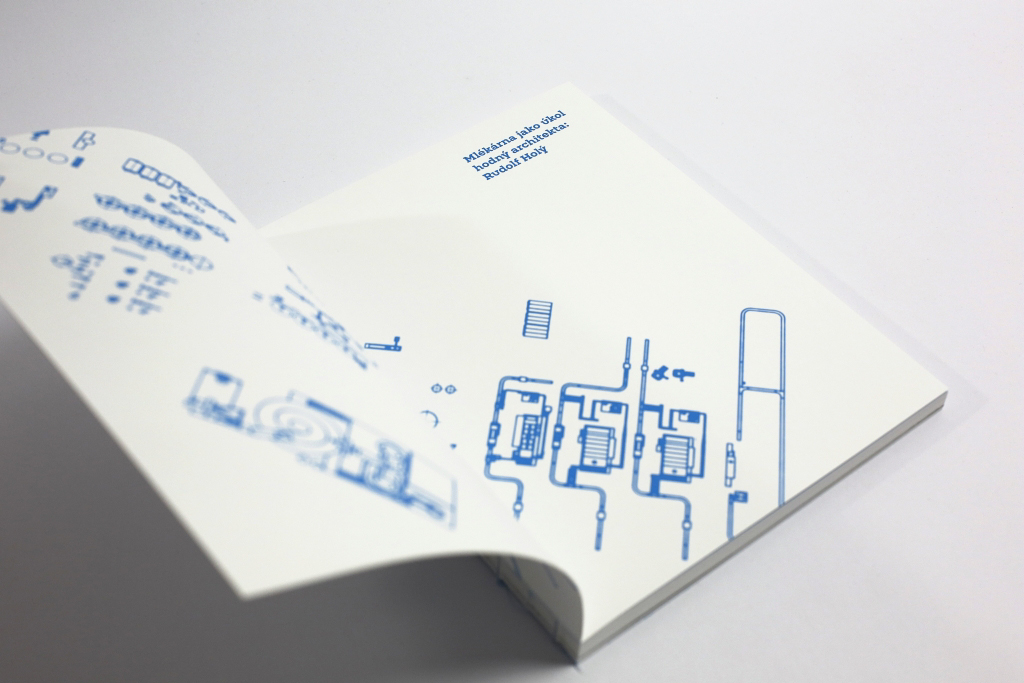

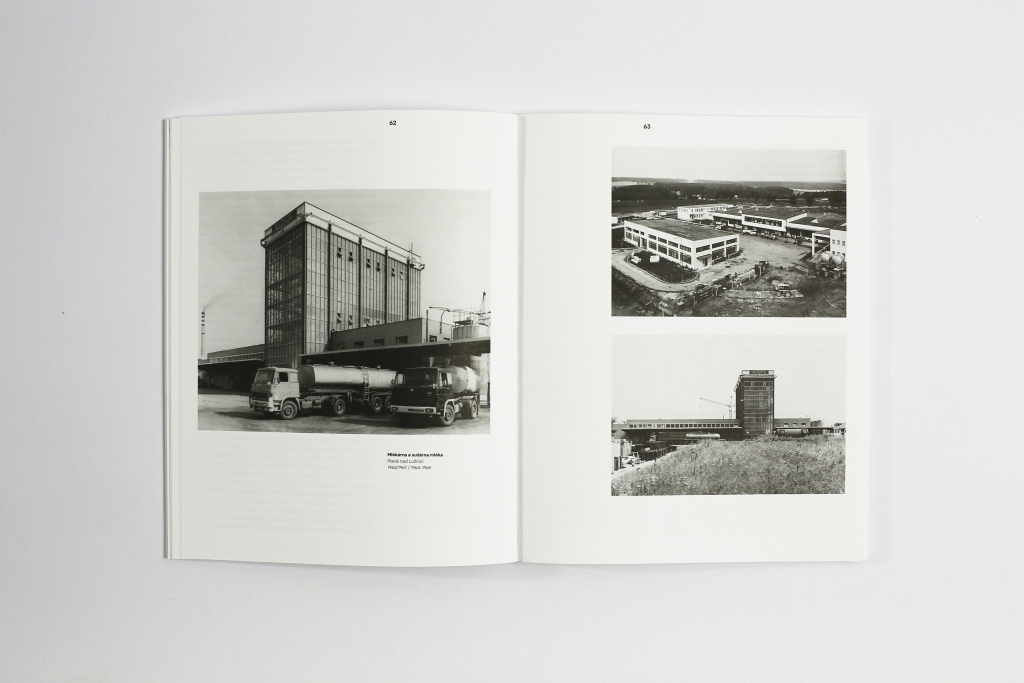

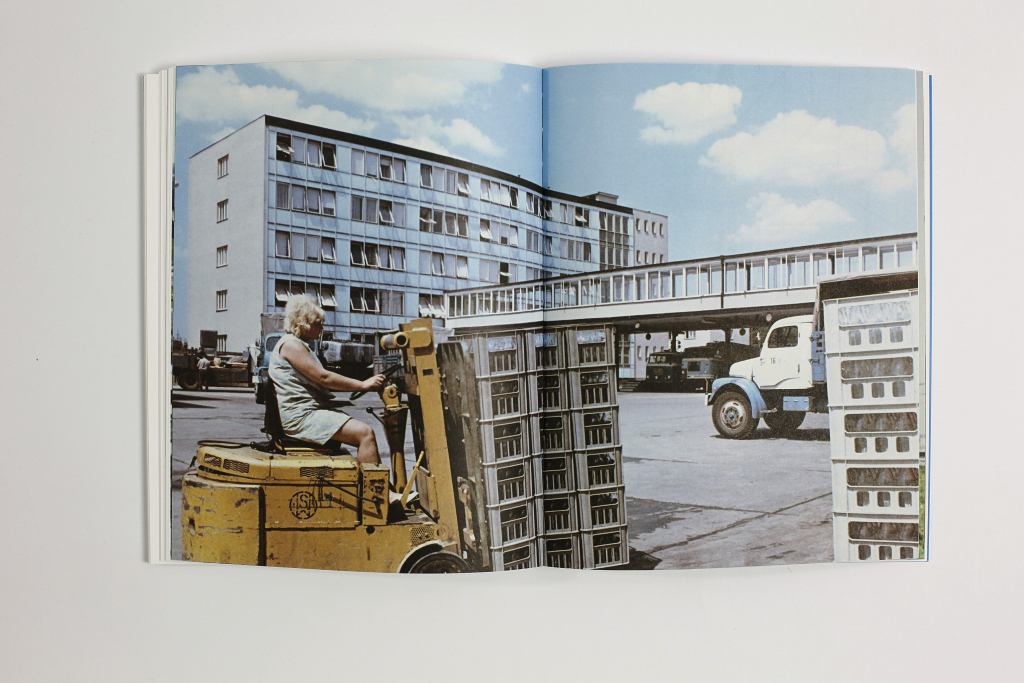

Architect Rudolf Holý (1930–2015), who is the subject of this book, was in the front line of all these changes. Holý studied at what was then the College of Architecture and Construction at the Czech Technical University in Prague (Vysoká škola architektury a pozemního stavitelství, České vysoké učení technické), where he studied under František Čermák, an expert in public health and hospital architecture, and Otakar Štěpánek. Although Rudolf Holý had initially wanted to devote himself to healthcare architecture upon completing his studies, he ultimately made his career in industrial architecture. After spending three years at Hutní Projekt, the design institute for the metal industry, Holý moved to Potravinoprojekt, the planning institute that provided designs for factories in the food industry – sugar refineries, breweries, malting plants, distilleries, canning factories, dairies, meat-processing plants, freezing plants, mills, and grain and other storage facilities. Within just a few years Rudolf Holý became one of the country’s best industrial architects. He specialised in modern dairies and powdered-milk production plants – large-scale operations using advanced technologies and designed according to the latest ideas in the field of operations economics. Although like other architects Holý had to contend with limitations to the possibilities open to contracting enterprises, the lack of availability of necessary materials, and the complicated dealings with investors, even in these conditions he was able to see through his architectural objectives and carry on the tradition of high-quality architecture in the dairy industry in Czechoslovakia, a tradition that established itself in the 1920s and especially the 1930s and continued until all construction activity was banned during the Nazi Occupation of Czechoslovakia.

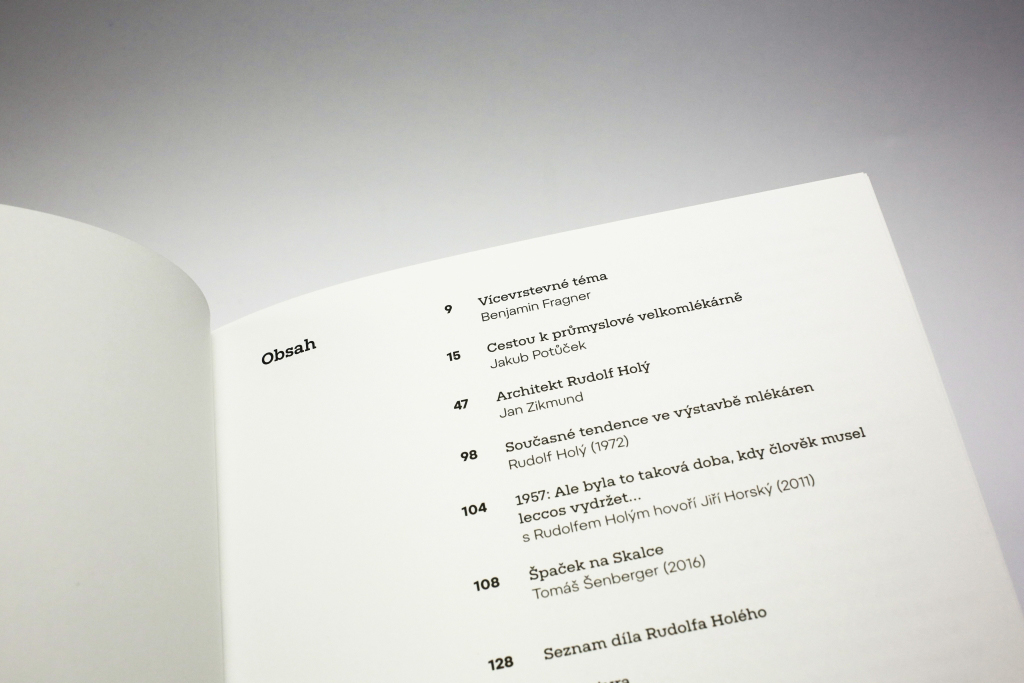

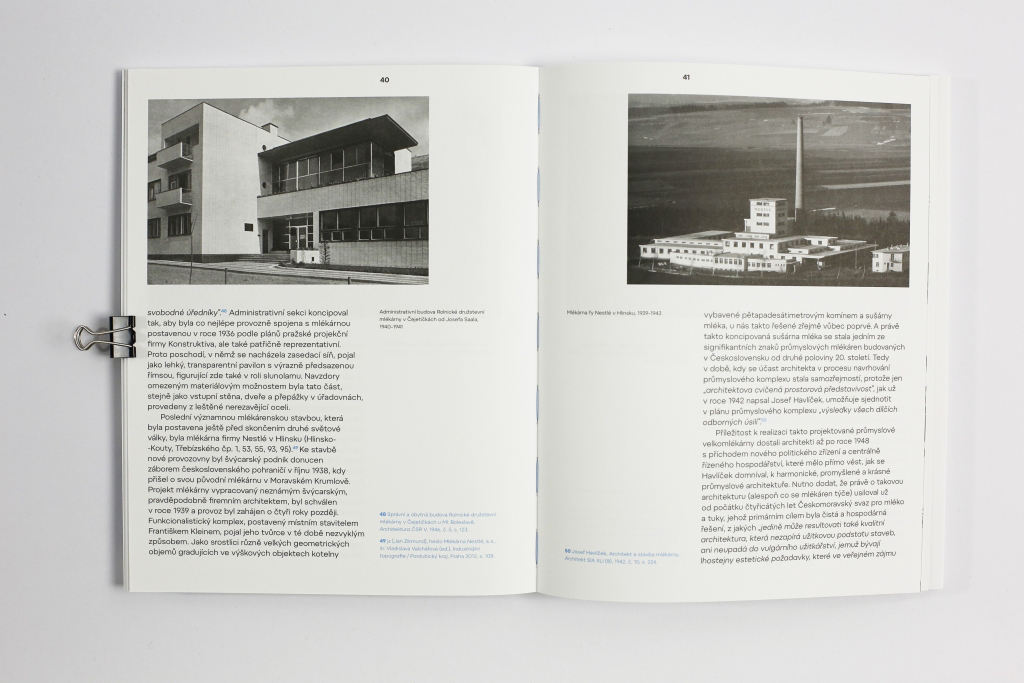

This tradition is described in this book’s opening chapter, ‘On the Path to Industrial Dairies’, which traces architecture’s first forays into the dairy industry, where initially much more importance was placed on machinery than on what the production hall was like. A major role in architecture’s advances in this industry was played by the Union of Dairy Cooperatives (Svaz mlékařských družstev), which, in addition to organisational and operational affairs, also oversaw the design and construction of new dairies. Thanks to the work of the Union, the dairies that were being built began to have undeniable architectural ambitions, and they were designed by emerging architects such as Josef Danda, Eduard Žáček, Josef Franců, Karl Ernstberger, Josef Lipš, and others. It was the possibilities offered by functionalism that introduced architecture with an artistic flourish into the construction of dairies and that were behind the origin of post-war designs for large-scale operations.

The core chapters in this book, by Jan Zikmund and Jakub Potůček, are accompanied by an article by Rudolf Holý, ‘Current Trends in Dairy Construction’, which describes the real problems that dairy architects had to address in their work. The book closes by presenting a picture of the life of Rudolf Holý described in an interview with Jiří Horský and in the personal memories of architect Tomáš Šenberger.

As Benjamin Fragner points out in his essay in the opening of the book, this publication also introduces the hitherto overlooked subject of post-war industrial architecture as explored within the framework of the NAKI II project ‘Industrial Architecture: Industrial Heritage Sites as Works of Architecture and Technology and as Sources of Place Identity’ (Industriální architektura. Památka průmyslového dědictví jako technicko -architektonické dílo a jako identita místa). The results of the research from this project will be summarised in a large monograph mapping post-war industrial architecture in a comprehensive overview stretching from 1945 to the demise of state planning work in the early 1990s.

Summary translated by Robin Cassling

Jakub Potůček – Jan Zikmund et al., Designing Dairies – A Job Worthy of an Architect: Rudolf Holý, Prague 2016.

144 pages; Czech/summary in English and German; 82 images and plans; ISBN 978-80-01-06041-4 / authors Jakub Potůček, Jan Zikmund / co-authors Benjamin Fragner, Jiří Horský, Tomáš Šenberger / scientific review Petr Kratochvíl, Petr Urlich / proofreading Hana Hlušičková / translation Robin Cassling, Susanne Spurná / graphic design Jan Forejt / treatment of reproductions Jiří Klíma / production Gabriel Fragner / font Pepi and Rudi / paper Munken Lynx / print Formall / published by the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage FA CTU Prague